The Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge has one of the largest populations of black bears in the eastern United States, like these two that posed for Sam Bland.

Supporter Spotlight

EAST LAKE – The caravan of cars wound its ways through the wilds of Dare County as dusk approached. The drivers hailed from Maine and Connecticut, Texas and Ohio, Virginia and Manteo. They had all come to see bears.

The folks at the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge provide that opportunity with their free Bear Necessities program each Wednesday through August. Participants meet at the parking lot of the Creef Cut Wildlife Trail at U.S. 64 and Milltail Road in East Lake.

Before taking off in search of black bear, they were met there by Kate Hankins, an intern with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The agency runs the refuge.

She gave them history about the refuge system, noting that President Theodore Roosevelt created the first national wildlife refuge in Florida in 1903 to protect birds from hunters who wanted the feathers for ladies’ hats. There are now more than 560 national wildlife refuges in the country, 10 in North Carolina.

Refuges are different from national parks, Hankins noted. The parks were created to cater to humans, while refuges are “wildlife first,” she said.

Supporter Spotlight

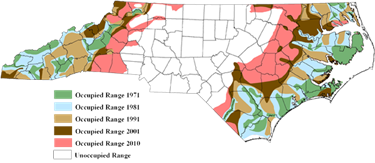

The occupied range of black bears in North Carolina has expanded dramatically since the early 1970s. Map: N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission |

The Alligator River refuge, Hankins told the expectant group, is home to the largest population of black bears in eastern North Carolina and one of the largest in the eastern United States.

Black bears are typically shy of humans. For this reason, feeding wildlife in general, but especially bears, is discouraged. If bears start coming toward people, it is not good for either species, she said.

“Our bears are mostly herbivores,” Hankins noted, explaining that they eat berries, grubs, roots and insects. “They’re not like our red wolves that will go attack a deer.”

A large mounted black bear skin was draped over the “DO NOT FEED OR DISTURB BEARS” sign, and participants were allowed to touch it and wear it and take pictures.

The bears have two layers of fur, Hankins said. Guard hairs on top keep them dry and a dense under layer keeps them warm.

She pointed out how large the nose and ears were, and how their senses of smell and hearing are much better than those of humans.

“Not all black bears are black,” Hankins added.

All in the refuge are, she explained, but environmental factors are thought to contribute to the fur color. Cinnamon, whitish and brown black bears also exist, Hankins noted.

Bear cubs stay with their mother for more than a year, she said, and many “yearlings” have been seen in the refuge. Staff members have also seen “really little fluff balls just coming out of the den,” she said.

“They’re very strong family units. Don’t walk between a mother bear and cub,” Hankins advised.

“You may have noticed the barbed wire along 64,” she said at one point, gesturing across the street.

Hankins explained that the barbed wire on the guardrails is part of a study to see where and what animals cross the road. The interns walked a section of the roadway and collected fur that was caught on the barbed wire — bear fur on the top wire and fur from smaller mammals like raccoons on the lower wire.

The animals have habits and trails they usually follow, Hankins said. The study will help determine where to build underpasses or other crossings for wildlife if the road is widened.

The caravan of cars through the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge is in search of bears. Photo: Corinne Saunders |

Then, it was to look for bears. A refuge truck led the way and another brought up the rear. Participants drove in their own vehicles on the gravel roads of the refuge.

The evening was quiet, with the slow crunching of gravel as the main background noise. Layers of light gray clouds rolled into the formerly sunny sky.

Horseflies and deerflies, attracted to moving objects and carbon dioxide, bumped into vehicles repeatedly, often hitching a ride for several minutes at a time as the caravan of cars moved through dense forest into open emerald-green fields, stopping several times along the way. Less-menacing dragonflies darted by.

People in the lead refuge truck and in the first car said they saw several bears in the woods—a mom with two cubs and, separately, another adult bear—that all were quickly spooked and ran off before the people in later vehicles could catch a glimpse.

The scenery included towering pines, irrigation ditches and farmland with meticulous rows of young, bright green crops.

Before the final turn of the drive, two bears were spotted at the far end of a field, on the edge of distant woods. Many participants stepped out of their cars and took turns with binoculars and cameras to try to see the bears.

The interns apologized that more bears had not been seen along the drive; it was an atypical outing in their experiences so far, they said.

But the bears are surely out there, and those interested can drive by themselves or show up for another Bear Necessities program, which ends at 7 p.m. You can then stick around and listen for red wolves howling. That program begins at 7:30 p.m. at the same location.

For more information, call 252-473-1131.