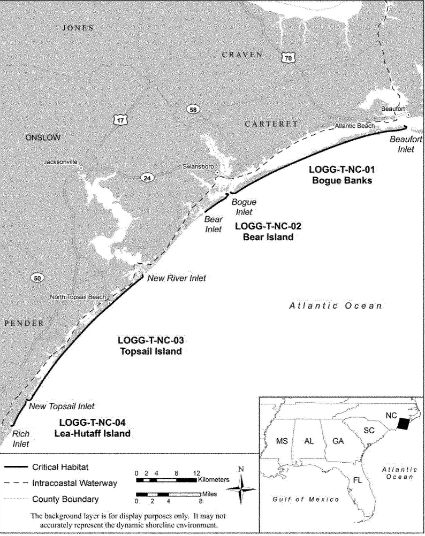

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is proposing that these beaches along the N.C. coast be designated as “critical habitat” for endangered loggerhead sea turtles. Source: USFWS |

Beach re-nourishment advocates and local government officials in North Carolina say a federal plan to increase protection of loggerhead sea turtles is a threat to crucial re-nourishment of tourist-luring beaches, but the federal wildlife officials say the critics’ contentions are overblown, if not totally baseless.

The “critical habitat” areas proposed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service encompass 739 miles along the Eastern Seaboard. In North Carolina, the areas total 96.1 miles of beach, including all or portions of Bogue Banks in Carteret County; Bear Island, a part of Hammocks Beach State Park in Onslow County; Topsail Island in Onslow and Pender counties; and Lea-Hutaff Island, Pleasure Island, Bald Head Island, Oak Island and Holden Beach in the Cape Fear region.

Supporter Spotlight

The proposed rule was published in the Federal Register on March 25 and is the result of a legal settlement between the conservation groups Center for Biological Diversity, Oceana and Turtle Island Restoration Network and the U.S. government. The groups had sued the government under the federal Endangered Species Act for failing to designate habitat critical for the loggerheads’ survival. Such designation are required after a species is listed, and the turtles are considered “threatened” under the law.

According to Chuck Underwood of the Fish and Wildlife office in Jacksonville, Fla., the agency has already heard a lot from organizations and local governments concerned about potential effects on the beach re-nourishment. Among those who have raised red flags are the Carteret County and Emerald Isle commissioners, who at recent meetings approved resolutions opposing the proposal. NC-20, a partnership of local governments and businesses dedicated to economic development in the state’s 20 counties, also adopted and circulated a resolution opposing the designation.

“The designation of critical habitat 35 years after the listing of the loggerhead sea turtle (as a threatened species) is the wrong management tool for the conservation of the species,” the resolution adopted by Carteret County concludes, “and the Carteret County Board of Commissioners will continue to support the protection and recovery of the loggerhead seat turtle by utilizing effective management guidelines and rules already in place, while evaluating new practices as they develop,”.

| Submit CommentsThe U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will accept comments on the proposal through Friday.

They can be submitted online by going to the Federal Rulemaking Portal. Refer to Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2012-0103. Supporter SpotlightComments can also be mailed to: Public Comments Processing, Attn. FWS-R4-ES-2012-0103; Division of Policy and Directives Management; US Fish and Wildlife Service; 4401 N. Fairfax Dr., MS 2042-PDM; Arlington, VA 22203. |

Greg “Rudi” Rudolph, Carteret County Shore Protection manager, recommended the resolution and called the critical habitat designation “unnecessary” and potentially burdensome, especially since the loggerhead has been protected by the federal Endangered Species Act since 1979.

“It adds another layer of review any time you do a federal project,” he said. “I’ve done a lot of homework on this. It would mean projects would get a great deal more scrutiny. It would require ‘special management considerations,’ and my fear is that those are not articulated. So even if (Fish and Wildlife) says this is benign, I wonder. If it’s so benign, then why are they even doing it? Our beaches are crucial to us.”

The American Beach and Shore Preservation Association, headed by Harry Simmons, who is mayor of Caswell Beach on Oak Island in Brunswick County, also has gone on record. In a headline on a recent press release, the association put it this way: “A new rule on habitat might end up pitting healthy beaches against healthy turtles – and that’s an unnecessary conflict that ends up benefiting neither.”

“The proposed rule,” according to the group’s press release, acknowledges “a nourished beach that is designed and constructed to mimic a natural beach system may benefit sea turtles more than an eroding beach it replaces.” However, it claims a larger proportion of turtles abandon attempts to nest on engineered beaches compared to natural beaches, due chiefly to physical differences between the two after construction.

Also cited by the rule as interfering with nesting are groins and jetties, coastal development, recreational beach use, predation, and the increased severity of tropical storms caused by global warming, among other elements.

”No one will argue against protecting loggerheads, but the broad designation advocated by USFWS may not achieve much protection – and could bring with it a significant cost,” the association concluded in its press release. “Failure to adequately restore eroded coastlines would not only reduce the nesting habitat for turtles (who thrive on a wide natural beach), it could pose significant threats to coastal economies (who thrive on the visitors and residents healthy beaches bring), to recreation (since beaches are more highly used that all our public parks combined) and to private properties and public infrastructure (which are best protected by wide beaches and high dunes to keep storm waves away). This potentially pits turtles against people – and that’s just not necessary or productive.”

Fish and Wildlife officials are quick to point out that the designation would only affect federal projects or activities that require federal permits. No such permits are needed to walk the beaches included in the proposal, to drive a vehicle along them or build a house beside them.

Underwood said the agency recognizes there’s a benefit – increased nesting area – for turtles as a result of beach re-nourishment. And, he said, the association’s reference to the language on “engineered” beaches is misleading.

Engineered beaches, he said, generally refers to beaches that wouldn’t even exist without man’s efforts to put them there and keep them in place. He said he knew of only a few in Mississippi and Alabama, where the sand is packed extremely tight; that’s what the agency doesn’t want.

Chuck Underwood |

Greg Rudolph |

He and Lilibeth Serrano, North Carolina spokesperson for the federal agency, said the designation should have no significant effect on re-nourishment projects that have already been approved or are underway and would have little or no negligible effects on private landowners. That’s important, because 81 miles of the 96 to be designated in North Carolina are not in federal or state parks.

Even if the habitat designation did come into play, Underwood said, all it does is add one more level of scrutiny to the review process. That process is already very thorough, because of the loggerhead’s listing under the Endangered Species Act, but the nourishment projects have routinely been approved.

The primary method of ensuring that the turtles’ nests are protected during projects, in fact, is fairly simple, according to Underwood. The Army Corps of Engineers, which heads up dredging and nourishment projects for North Carolina’s beaches, is given “windows,” timeframes in which the work must be completed, and those windows are outside of nesting and hatching season.

“I do understand the concerns,” Underwood said. “But it’s really not intended to have an impact on beach nourishment projects that have been approved in the past. The only problem would be a project – such as those I mentioned before – that would engineer the beach to the point where it wouldn’t support turtles anymore.”

The resolution Carteret County and Emerald Isle approved in opposition to critical habitat designation also mentioned potential impacts on the teams of turtle volunteers who walk the beach during nesting and hatching season, working to identify and protect nests and monitor hatching.

“…if critical habitat is designated, some of these existing and successful programs will be burdened with additional and unnecessary regulations, and therefore will become more costly, which will increase the threat to the loggerhead sea turtle and its habitat,” the resolution states.

Underwood said the designation wouldn’t impact those activities because federal permits aren’t required.

“Many … communities are already active in sea turtle conservation efforts along your local beaches,” he said. “This proposal is not meant to detract from those wonderful efforts; quite the opposite. These cooperative conservation efforts are contributing to loggerhead sea turtle recovery and conservation, and we have no doubt they will continue to do so into the future regardless where or if any particular line is drawn on a map.”

Nor would it affect tourists’ use of the beaches, Serrano added.

“This doesn’t change protections or management requirements that are already in place,” said Serrano said. “If a beach is currently open to tourists, that shouldn’t change.”

Sierra Weaver, a senior attorney at the Chapel Hill office of the Southern Environmental Law Center, said that organization is preparing comments to submit to USFWS in favor of the critical habitat designation.

And, she said, people shouldn’t worry about the proposal prohibiting nourishment projects.

“Under the ESA (Endangered Species Act), the federal agency has already had to consult to see if the project is going to harm the species,” she said, and that is why windows of time have been established for the projects. If critical habitat is designated, the corps would have to do a similar “consult” with USFWS to see if the project would harm the habitat.

What that means, in practice, Weaver said, is that project planners will have to make sure, for example, that the sand is of the right quality and color, and that its placement on the beach doesn’t impact the turtles.

SELC, she said, actually plans to request in its comments that the Fish and Wildlife Service designate a few other North Carolina beaches as critical habitat for the loggerheads, because the state’s beaches are of great importance for the survival of the turtle.

Florida, she said, has the highest concentration of loggerhead nests. But the temperature of the sand determines the sex of loggerheads, and Florida, since it’s hot, produces far more females than males. North Carolina, being farther north and cooler, produces far more males. And that, of course, is crucial.

“Designating critical habitat is very important for the loggerhead population, but it’s not doing to stop anything,” she said. “As long as projects are planned well and done like they are supposed to be done, they’ll be fine, and we’ll actually have more habitat because of the wider beaches.”

Despite what Underwood termed some groups’ and individuals’ “misunderstanding” of the impacts of critical habitat designation, he said his agency has agreed to hold public hearings on the issue later this summer.

“We received a number of these requests primarily along coastal North Carolina near Wilmington, as well as one location in South Carolina,” he said in a letter.

“We are publishing the draft economic analysis (EA) for the critical habitat designation proposal later this summer. At that time, the public comment period will reopen for at least 30 days to allow the public an opportunity to review and provide comments on the draft environmental assessment and provide additional comments or information on the proposal itself.”

Underwood said his agency will announce the times and locations of the hearings later, because he expects there will be additional requests.