OCRACOKE — On a chilly morning in January, an unlikely group of men, women and children congregated around a large wooden table in a rambling old building on an Ocracoke Island dock. Warmed by an old-fashioned pot-bellied wood stove, they studied the array of oddly shaped objects on the table.

Their common interest was drawn to what scientists know as Crassostrea virginica, or the eastern oyster. The group had come together to start a research project that will study the larvae, or spat, of local oysters.

Supporter Spotlight

They gathered around the old pot-bellied stove in Ocracoke to learn how to save the oyster. Photo: Pat Garber |

Ocracoke resident Elizabeth Hanrahan, coordinator of the Ocracoke Foundation’s “Outdoor Classes” project, had teamed up with Troy Alphin and Marc Tarano to organize the meeting. Alphin is with the Center for Marine Science’s Benthic Ecology Lab at the University of North Carolina Wilmington and Tarano is with North Carolina Sea Grant. Their mission is to train volunteers to participate in the university’s project to monitor baby oysters, or spat. It’s part of a multi-faceted approach to learn more about the causes and solutions to the recent decline in North Carolina’s oyster populations.

Jennifer Garrish, Ocracoke School’s science teacher, was among those huddled around the table. She is encouraging her students to fulfill their community service hours required for graduation by participating in the project. James Barrie Gaskill was also at the table along with Robyn Payne. An Ocracoke commercial fisherman and a N.C. Coastal Federation board member, Gaskill has been actively involved in oyster restoration. Payne is president of the Ocracoke Foundation, which provided the space for the meeting. An assortment of local men, women and children interested in oyster restoration filled out the group.

Along with being a popular food and a valuable source of jobs, oysters play several important roles in marine ecosystems. They filter water as they feed, and studies show that one oyster can filter 25 to as much 50 gallons of water a day in their quest for food. In the process they cycle nutrients and nitrogen through the water and clean the water of pollutants. Oyster reefs provide habitat for a large array of marine life, including algae, barnacles, mussels, sea squirts and tube worms. Small fish and crabs take refuge among the shells, feeding and providing food for other sea life. As biogenic structures, oyster reefs provide erosion control for the marshes and lessen the damaging effects of waves during storms.

North Carolina’s oysters have been declining as a result of over-harvesting, increased stormwater runoff and the resulting pollution, disease, habitat destruction and the influx of invasive species. Locally, siltation, salinity, water temperatures and infestation by boring sponges effect oyster survival.

Oyster restoration has, therefore, become a high priority in state and university research. It has been determined that the best way to bring oysters back is to build reefs from oyster shells, known as cultch. Oyster restoration projects coordinated by the Ocracoke Working Waterman’s Association and the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries at Ocracoke include placing loose and bagged oyster shell at promising sites located by local watermen.

Supporter Spotlight

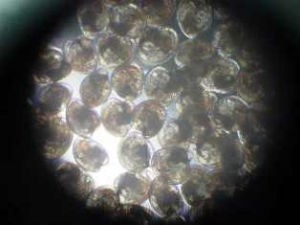

Before oyster restoration can begin, it is important to understand the oyster’s life cycle. Oysters release pheromones and gametes — eggs and sperm — into the water. The newly formed oyster larvae float freely at first and may travel relatively long distances in their first 10 to 14 days, depending on the tides and currents. They must then find a place to attach, or “set,” however, or they will die. Their favorite material for attaching is oyster shell, which they identify by touch and by “tasting” the bottom. When the oyster larvae touch an oyster shell, they stop. These tiny oysters are called spat

The oysters continue to grow, some as singles and some in clusters. Oysters which live in clusters have more protection from predators such as blue crabs, whelks and large oyster drills. They also have more effective reproduction. Although the eastern oyster does not have a deterministic lifestyle and may live a decade or more, most oysters in Ocracoke waters die, according to Gaskill, by the time they reach four years of age.

Oyster spat as seen through a microscope. Photo: Skip Kemp |

UNCW has been studying North Carolina oysters since 1993, and Troy Alphin, Martin Posey and Tarano first started the volunteer project in 2007. Since then, there have been more than 70 different monitoring sites in North Carolina. Today there are 47 active sites, with 186 volunteers, including four or five school groups. The majority of sites have been along North Carolina’s southern coast, so setting up the new sites in the more northerly waters of Ocracoke is an important step.

In order to know where to put the oyster cultch, said Alphin, it is necessary to know where and when the larvae are in the water column, the density of larval set, how much habitat is available and variation in settlement patterns. His oyster spat monitoring project focuses on the last of these. It is designed to determine the “density of set,” which means how many oyster spat settle in a certain area in a certain length of time.

The study, Alphin explained, uses old ceramic tiles, which have been found to attract oyster spat at about the same rate as oyster shell. The tiles are tied together in a “spat racks.” Each site requires two racks with tiles, a thermometer for testing air and water temperature and a hydrometer for testing water salinity. The cost of outfitting a site is $45 to $50. A waterproof notebook is provided for making notes. The first spat rack is set up in waters and at levels where oysters are believed to attach, and left for six weeks before being retrieved and recorded. After four weeks the second rack is set nearby, also for six weeks, and then examined. This process is repeated over and over.

Researchers want to know how many live oysters, how many “oyster scars” — left by dead oyster spat — how many barnacles, how many barnacle scars and what associated fauna are to be found on the tiles after a six week period. This will tell them where, when and how densely the spat are in the water column. Volunteers are also asked to record such things as cloud cover, rough seas and the presence of worm tubes, Bryzoans, sponges, hydrozoans and sea squirts on the tiles. UNCW then makes the data obtained from the study available for other researchers and state officials to use.

“The result is a completely unique data set that provides a picture of when and where oysters recruit along the north, central, and southeastern coast of North Carolina,” Alphin noted.