First of four parts

The quiet piney woods of the N.C. coast are a long way from the bustle of Berlin, London and Amsterdam, but those trees may soon be lighting up those far-off foreign capitals thanks to the unlikely convergence of European eco-policy and abundant Southeastern pine trees.

In a sort of back-to-the future moment, Europe is turning to the fuel source of the Middle Ages to fire up its power plants and is looking increasingly to Southern states to supply it. Europeans have circled back to the past because policy makers there think they know something futuristic that the dukes of Cornwall or the earls of Hapsburg couldn’t conceive centuries ago when they threw another log in the fireplaces of their medieval castles: Wood is “green.”

Supporter Spotlight

The European Union considers wood to be a renewable energy source that is also “carbon neutral,” meaning that it won’t worsen global warming by adding additional carbon dioxide to the atmosphere when burned. Coal, which is the primary fuel for generating electricity in Europe as it is in North Carolina, is neither of those things.

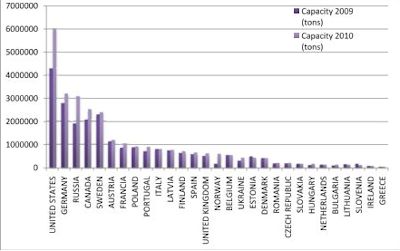

Wood pellet production by country: The highest increase in production capacity was in North America and Russia,followed by traditional European-producing countries,such as Germany, Sweden and Austria. Source: Global Wood Pellet Industry Market and Trade Study, IEA Bioenergy, Dec. 2011. |

European countries in 2009 instituted ambitious policies that encourage power companies to cut their emissions of greenhouse gases and increase their use of renewable energy sources by 20 percent in 10 years. Utility companies responded by switching from coal to wood pellets, pencil-sized, compressed forms of wood that burn more efficiently and transport more easily than logs.

And they’ve been doing it with gusto. The consumption of wood pellets in Europe has increased almost 50 percent since 2008, far outpacing the ability of the continent’s forests to meet the demand, which is forecast to continue its dramatic rise for the rest of the decade.

The growth has ignited a boom here in the United States, transforming what had been a small industry that made wood pellets from sawdust to heat homes in New England into a rapidly growing export trade of pellets made primarily from Southern trees. The dense forests of the Southeast have long been one of the globe’s wood baskets, and those trees have now propelled America into the world lead in the production of pellets. At least 30 pellet plants have been built or are proposed – many with the financial backing of Europeans – in Georgia, South Carolina, Virginia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and, most recently, North Carolina, according to a study done last year by the Southern Environmental Law Center. All but one of the existing plants have opened since 2008.

To cash in on the boom, the N.C. State Ports Authority announced plans late last year to invest as much as $200 million at its two sleepy ports in Wilmington and Morehead City to ship pellets made in North Carolina to Europe.

Supporter Spotlight

Using the state’s coastal forests as fuel depots for foreign countries raises numerous questions that should be considered before we rush off into the woods with chain saws roaring. We’ll explore some of those questions here over the next four days: Can our forests handle all this cutting and still maintain their aesthetic qualities and their ecological importance to wildlife and water quality? Does the state have policies in place to prevent clear cutting and ensure that cut tracts are replanted? What will increasing train and truck traffic mean in Morehead City, whose residents and businesses rely primarily on tourists for their livelihood?

Is Wood Really Green?

Driving the overseas policies that will affect the forests of the N.C. coast is the assumption that wood pellets are better than coal, that burning them will not overheat the planet. But is it true? In other words: Is wood really green?

Will McDow of the Environmental Defense Fund in Raleigh has spent a great deal of time studying what’s known as “bioenergy,” which refers to renewable energy contained in living or recently living biological organisms. Organic material, such as plants and trees, contain bioenergy that is known as “biomass.”

Christopher Galik |

Will McDow |

We first posed the question to McDow two years ago for the federation’s State of the Coast Report on renewable energy. This is what he said then: “It’s a shade of green. It’s a very challenging subject. You have a lot of cheerleaders out there and you have the naysayers. It depends on how you collect it, what you use and how you use it.”

Like many environmentalists, McDow supports biomass as a future fuel because it’s renewable and less polluting than coal, but he also knows that, as with any fuel source, there are tradeoffs. Relying on the trees of a few U.S. states to power a continent could have serious implications, he said recently.

“We’re very reluctant to draw black and white lines in the sand,” said McDow, who co-wrote a study last year on the implications of pellet plants in the Southeast. “But we have to raise these questions. We don’t want to see so much capital investment that it overshoots our forest inventory.”

Burning wood produces various emissions that would have to be controlled and, like coal, creates carbon dioxide, a powerful greenhouse gas. Promoters like to claim that wood is “carbon neutral” because the trees soak up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they grow, and that balances out the CO2 they produce when burned.

It’s not that simple, though, noted Christopher Galik, senior policy associate at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions. “We stay away from the term ‘carbon neutral,’” he said. “It’s a more nuanced story.”

It all depends on where the wood comes from, how it’s harvested, whether whole trees or wood waste — such as tops, limbs and sawdust — are used and if the land is replanted with trees afterward.

These varied conditions and the actual method used to account for the carbon explain the mixed research results. Some studies show a no net gain in carbon emissions when burning wood pellets, while more recent studies suggest that burning pellets actually emits more CO2 than an equivalent amount of coal.

The ‘Carbon Debt’

The Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences in Massachusetts did probably the most famous and influential study on the subject in 2010 for that state’s Department of Energy Resources. The study blew a major hole in the carbon-neutral theory. It concluded that there’s a carbon “debt” when biomass is burned for energy and that burning trees or other types of biomass often releases more carbon at the time of combustion than an equivalent amount of fossil fuel. It then takes a certain amount of time to repay that debt by recovering that additional carbon.

A wood pellet plant in Ahoskie. |

In other words, the CO2 released from burning a large pine tree, say, would exceed what’s emitted by an equal amount of burned coal. The extra CO2 wouldn’t be recovered for years, until a new pine tree grows large enough to take up the extra carbon through photosynthesis.

The study’s researchers concluded that it takes about 42 years to begin to create a net carbon dividend compared to coal when biomass is used to make electricity.

Researchers for the Southern Environmental Law Center came up with similar findings in their study. Based on current trends in using wood for utility-scale power plants and exporting pellets to Europe, biomass energy in the Southeast is projected to produce higher levels of atmospheric carbon for 35 to 50 years compared to fossil fuels, they concluded. After that, biomass will result in significantly lower atmospheric levels as re-growing forests absorb carbon from previous combustion.

“The timing problem is central to this issue, since adding even more carbon from biomass to the atmosphere over the next 35 to 50 years could accelerate global warming stressors,” said Julie Sibbing, director of agriculture and forestry with National Wildlife Federation. “We run the compounded risk of losing forests to severe weather events triggered by climate change, such as droughts and flooding, undermining their ability to sequester carbon over the long run.”

The Carbon Inventory

The law center study also predicted that whole trees, and not just limbs and other wood “waste,” would have to be used to meet the demand of European utilities. If the logged tracts aren’t replanted – and there’s no law in North Carolina that would require that on private land – then even any future carbon savings would be jeopardized.

Trees store a lot of carbon during their lifetimes, McDow noted. Reducing future forest cover would likely lead to even higher increases in future atmospheric CO2.

“In past debates on forestry issues, we always argued about having enough trees,” he said. “This has changed the debate to can we do this in a way that doesn’t reduce the carbon inventory.”

Ninety scientists and researchers on this issue made the same point in a letter to Congress in May, 2010. “… clearing or cutting forests for energy, either to burn trees directly in power plants or to replace forests with bioenergy crops, has the net effect of releasing otherwise sequestered carbon into the atmosphere, just like the extraction and burning of fossil fuels,” they wrote.

Wednesday: The potential effects on coastal forests