“…this ever changing world in which we live in.” — Sir Paul McCartney

HAMPSTEAD — N.C. lawmakers this year passed a piece of climate-related legislation — H819, An Act to Study and Modify Certain Coastal Management Policies. After its passage, the bill was met with some disdain by environmentalists along with considerable ridicule in the political comedy circuit—worldwide. But opinions of pundits and commentators regarding the controversial legislation are less important than the confusion it caused in communities where consequences of climate change, including sea-level rise, are already observable and creating impacts that we ignore at our own peril.

H819 has created confusion among some people on the N.C. coast because the bill rather blatantly disregards a new coastal reality that even casual observers can attest. I’ve spoken to watermen and women who talk in matter-of-fact terms about coastal changes they have personally seen over just the past few decades; changes including once-exposed oyster reefs now submerged even at low tide, grassy marshes that are now open water and once lush forests now grassy marshes. These observations come from people who make their living in and on our coastal waters, including Bill Moller. With his wife, Tina, he operates Nature’s Way Farm and Seafood near Hampstead in Pender County.As a commentator about matters environmental, I realize there is risk in opening a conversation with a personal affirmation of climate change, mostly because my words may prompt some people to turn away from anything else I have to offer. That said, please know that this piece is not just another global-warming rant meant to coerce people to believe in climate change. Nor is it a criticism of state lawmakers. This is a piece about the power of observation, with emphasis on the role each of us can play when it comes to keeping track of the world around us.

Supporter Spotlight

Bill has been harvesting and selling fish and shellfish for over 25 years, and like many watermen, he is pretty matter of fact when it comes to coastal issues. When I asked him recently about oystering in Topsail Sound, adjacent to Stump Sound, he volunteered that his favorite places to “knock oysters” are now only accessible with oyster tongs.

In his no-nonsense manner, Bill said, “I can show you oyster reefs that used to be exposed at high tide, but now are under water at low tide.”

When I asked him what he thought was behind the change, he grinned and replied, “What do you think? The ocean’s coming in.”

While we are friends, his good-natured tone still made me feel like a landlubber; like I didn’t know of the existence of tides or that the sun rises from the east and sets off to the west.

With Bill’s observation as segue, I’ll note here that this commentary is supposed to be about horseshoe crabs and sand dollars — in our area more correctly called keyhole urchins. This subject arose this past summer when Susi Hamilton, who represents New Hanover County in the N.C. House, viewed both of these animals for the first time in a long while in Stump Sound.

Supporter Spotlight

Susi Hamilton, a state legislator, wondered about all those horseshoe crabs in Stump Sound. |

Susi grew up in and around Wilmington and she knows Stump Sound near Topsail Island from countless visits throughout her life. This spring, while exploring the sound with her family, she noticed numerous small horseshoe crabs, along with a gathering of sand dollars. Since she had not seen either of these animals in several years Susi brought her observations to the attention of the N.C. Coastal Federation, simply out of curiosity, wondering what might explain their sudden reappearance.

I got involved in the matter during a conversation with Frank Tursi, the editor of federation’s online news service. Frank asked me if I had any thoughts regarding the issue, and the first one that came to my mind was another organism: the Scotch bonnet, North Carolina’s official State Shell. Why the Scotch bonnet? Well, it has to do with sea-level rise, but more to the point, this predatory marine snail preys on sand dollars. I’ll come back to this thought in a moment.

In nature, change is the only constant, and nowhere is change more evident than in and around the dynamic interface between land and sea. Stump Sound, along with the barrier island (Topsail) to its east, and the mainland shoreline (Pender and Onslow counties) to its west already show obvious signs of change, including rising salinity in the sound itself, along with marsh and fringe forest drowning all around the sound’s perimeter. And of course there is also the inconvenient truth regarding Topsail Island’s eroding north end, a natural result of ocean and sand interplay.

Frank wondered if Susi’s observation had something to tell about change and when he told me someone who knew Stump Sound thought it was odd that horseshoe crabs and sand dollars were suddenly showing up, I suspected changes in the sound’s salinity might be in play.

Horseshoe crab prefer salty waters. Can their appearance in Stump Sound signal a change in salinity because of climate change? |

Horseshoe crabs can tolerate brackish water, but they prefer salinities near that of the open ocean – 32 to 35 parts per thousand — and the same is true for sand dollars. I could fill paragraphs with speculations about this one observed goings-on in nature, but there’s not much point in doing so here, especially absent other information, collected in a scientific process, including background weather conditions and patterns across multiple years. Back to back annual droughts, for instance, can raise inshore water salinity. Horseshoe crabs are sensitive to certain bacteria pollution, which brings into play water quality changes. And of course, it’s helpful to have results of dedicated surveys — if any exist — to determine horseshoe crab and sand dollar population densities.

I can’t offer a definitive reason to explain the encounter Susi had with these two marine animals. But I am curious to know if this was a chance event or not. And the only way to answer that question is with more information, which has to be collected by someone and we can’t expect professional scientists to be able to do all of the work for us. I can promise to keep my eyes open for signs of Scotch bonnets in Stump Sound, if only to track next steps in that sound’s climate influenced evolution.

Professional scientists do a great job with the tasks they have at hand, whether trying to pinpoint the origin of a particular carbon molecule, which we now can do, in an effort to identify sources of global air pollution or monitoring the flowering cycle of a wildflower, which we have been doing for thousands of years. It’s all about a scientific process, beginning with observation. Our challenge, as scientists, is finding enough scientists to do all the work we need to accomplish in order to stay knowledgeable about a world supporting millions of plant and animal species with a diverse assemblage of habitats that have evolved over time, in response to cyclic climate changes.

And this is where Bill the waterman, and Susi the state legislator come in, along with each and every other one of us. We need to ramp-up our observation skills, make note of what we see, and share that information with other people so that we can make sound decisions regarding how we as a species are going to move forward on this changing globe we call Earth.

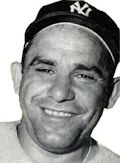

To underscore the point of this commentary, I will evoke a favorite quote of mine from that wizard of understatements, Yogi Berra, who once said: “You can observe a lot by watching.” I will add: You can also learn a lot from observation.

|

Pictures of Yogi Berra, top, and Henry David Thoreau don’t often appear together. But both are respected observers in their chosen fields. |

Arguably the most celebrated American observer of nature, including people as part of nature, is the 19th century educator Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), whose timeless writings, including his book Walden and his essay Civil Disobedience, have earned him recognition as one of the most important American philosophers. Thoreau’s writings have moved and influenced many great thinkers, including such familiar 20th century leaders as Theodore Roosevelt, Martin Luther King and even Mahatma Gandhi.

Thoreau once disdained the moniker “transcendentalist” that was often attached to his name in favor of the more understandable and fitting title of educator. Thoreau was an educator and a consummate observer and recorder. In his exhaustive collection of journal notes, he apparently documented everything he observed, whether the old furnishings in a friend’s home or the timing of a goldenrod flower opening in autumn. He kept notes about much more than just observations in nature, because he knew natural history included the history of people, as evidenced by the things we built and kept. He was fascinated by all things around him, not just nature, and we know this from his journal entries.

I mention Thoreau because his 19th century observations in nature provide a priceless natural history picture of what his hometown of Concord, Mass., was like leading up to his untimely passing just as our nation was plunging into civil war, a matter of social interest that also interested and concerned Thoreau. But I digress.

We can use Thoreau’s journaling practice as a guide for tracking changes through the seasons here on the coast, and changes through the years, beginning with observations made by generations of coastal inhabitants.

So, from horseshoe crabs and sand dollars to cypress trees and submerged marsh, there is much we can learn from observing. But observing is not enough. We also need to document what we observe and share that information so that policymakers in positions to make change can do so responsibly and to the benefit of all living things because all living things are connected.

And few places offer more challenging decision-making choices for established communities than here on the N.C. coast.

During my conversation with Susi Hamilton, she paraphrased another favorite quote of mine, from one of Thoreau’s closest friends, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who offered in his very dense essay Self-Reliance: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” The operative word here is “foolish.” And the point Susi was stressing is the challenge she and her colleagues face when confronted with issues requiring resolution and decision-making that does not conform with party line, or sometimes, constituent opinions.

Which was the point Emerson was making when he followed with “…adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.” Yikes. Emerson could be harsh, and Thoreau always meant exactly what he said. These are two 19th-century observers and writers whose knowledge and insights are timeless, and, in my opinion, of great value to our 21st-century policymakers. In my opinion they should be required reading in the legislature. But again I digress.

So where do we go from here? Outside of course. Go outside, observe what you see, document those observations and make them known to others. You don’t need a personal blog or tweet account. Your observations in nature are no less valuable to scientists than their own. If you aren’t sure of what you are seeing, what kind of bird it is or snail, that’s fine. We can figure that out. The important thing is to observe. Even, and especially, observations of things once seen, but no longer.

Share your observations with others. It’s fun, helpful and important, especially as regards observations related to sea-level rise and other notable consequences of climate change. It’s also essential in this political system of ours, to take our observations to the desks of people in position to make changes we must enact sooner rather than later. Unless we are fine with letting nature (including people) do its/our thing, and we just wait for the consequences.

Another quote, this from the 20th century Polish writer Stanislaw Lec, who said: “Each snowflake in an avalanche pleads not guilty.” I add this because I think each of us has an ethical responsibility to accept reality for what we observe. To do otherwise is foolhardy at best and dangerous at worst.

Sir Paul McCartney is correct; we are part of “this ever changing world in which we live in.” We best pay attention.