Second of three parts

Reprinted from the Island Free Press

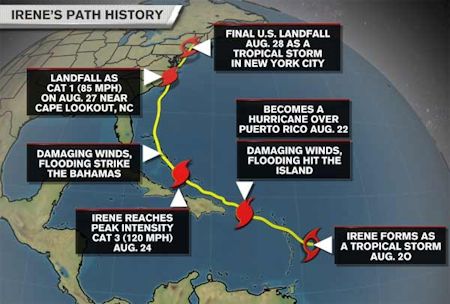

Source: Weather.com |

FRISCO — Even by Hatteras standards, Hurricane Irene, which hit the Outer Banks on Aug. 27 last year, was a real monster of a storm that even now continues to affect the island.

Supporter Spotlight

On first anniversary of the storm, I took a moment to reflect by reviewing notes I kept beginning with the evacuation and ending when the Pea Island Inlet Bridge opened about seven weeks later. It was an emotional read as I relived the memories of that time. There was a lot going on and so much to report that I had time only to write a part of what I reported or experienced.

Every aspect of Hurricane Irene took a long time.

When the storm finally started to impact the lower Outer Banks after dark on Friday, Aug. 26, residents had already had several days to prepare. An evacuation for tourists on Hatteras was ordered for Thursday, Aug. 25, and for residents on Friday morning, Aug. 26.

Those of us who stayed were calm but bored, waiting to get the storm over with. Donny, my husband and the Island Free Press photographer, and I drove around most of the afternoon looking for something to do — wind for windsurfing, waves for surfing, or even a story to report. Nothing much was happening.

We had electricity for much of the night and got to watch Island Free Press’ editor, Irene Nolan, get interviewed via phone by Greta Van Susteren on Fox News. Since Hurricane Katrina, there has been a lot of national media attention given to the folks who choose to not evacuate in the face of a hurricane, and Irene did a great job of explaining why we stay. The weather worsened overnight.

Supporter Spotlight

Gusty winds and driving rain can make for a fitful night’s sleep.

By Saturday morning, the electricity was long gone and it was time for camping coffee, which is made by slowly pouring boiling water over grounds in the coffeemaker. It takes a little patience, but it tastes unreal.

Strong northeast winds that preceded Irene blew water out of Buxton Harbor on Aug. 26. That’s never a good sign. |

A gas station in Avon lost its canopy. Photos: Don Bowers, Island Free Press |

With our personal gas-powered generator running to keep the refrigerator cold and a couple of lamps for our houseguests, Donny and I hit the road to do storm reconnaissance for the Island Free Press. At that point, there wasn’t a lot to report on. The winds were gusting off the ocean but not super strong yet. Rain came through in bands, which meant it either rained hard or not at all. The eye of the storm was getting closer but still not here.

We returned home for a while to wait some more and discovered our satellite TV worked, which enabled us to get some real-time hurricane updates. Forecasters were predicting the storm to impact the entire Atlantic seaboard from the Outer Banks all the way up to New England. All news stations had abandoned regular programming to bring millions of viewers the latest updates on the storm’s progress and evacuation orders were issued from several states. Intermingled with all the reports were newscasters demanding that everyone adhere to all evacuation orders, and they had unflattering opinions for those who would defy the orders.

Our next trip out, the winds had increased significantly but were still out of the east, which blew the Pamlico Sound dry. This is a huge concern for islanders because we typically get more flood damage from the sound, not the ocean. The easterly winds push the water west to the other side of the sound, which is more than 30 miles away. When the eye of the hurricane passes by, the wind usually shifts directions dramatically, which sends the piled-up water rushing quickly back across the sound and causes horrific flooding. This wasn’t a good sign.

In spite of this warning of things to come, islanders were out and about. People were snapping pictures and taking videos. There was some cell phone signal on the island, and folks were using their technology to upload images and information to Facebook to share. There were people shelling and scavenger hunting in the waterless sound bed.

Donny has experienced every storm since he moved here in 1966, and he kept watching the wind direction to judge the storm’s movement. It continued to stay easterly. As the day wore on, the skies got darker, the rains heavier and more frequent, and the winds got stronger. Before dark, we took one more trip staying away from areas prone to ocean overwash.

At this point, Hatteras had been in the hurricane for almost 24 hours and the worst was still ahead of us. Hurricane forecasters had delivered a troublesome forecast a couple of days earlier, predicting that this was the big one and to expect multiple inlets. Was this our last look at our island as we knew it? So far, the dunes had done their job and held most of the ocean back. But, the wind had started to switch more southerly. If the winds went due west quickly, we were in for some real trouble from the rapidly returning sound waters. But a slow shift in the wind direction might be our saving grace.

The ocean broke through the dunes in several places east of Hatteras village. Photo: Don Bowers, Island Free Press |

The evening was rather pleasant as we rejoined our house guests who had evacuated to our home, which is high and dry by island standards. We enjoyed sandwiches and wine by the glow of the lamps, powered by the noisy generator that ran outside. On TV, weathermen continued to track the storm’s progress and we endured the newscasters who called us stupid for staying in the path of this powerful storm. I was able to get on Facebook with my cell phone and saw disturbing photos of the Colington Fire Department up the beach with its furniture floating inside the building. We then knew the soundside flooding had begun.

We charged our cells phones, laptop computer, flashlights, and camera batteries by the generator before we turned it off for a second night of restless sleep as our barricaded house kept us safe from the powerful tropical cyclone that churned loudly outside for most of the night.

Morning came early, and I made another delicious pot of camping coffee. It was still dark outside as we strained our eyes to see if our house was surrounded by water. Our canal had flooded 75 feet towards our house, but, basically, we were high and almost dry. The first light revealed a lot of tree debris but nothing catastrophic. The wind noise had stopped just an hour or two earlier. We took to the highway to see how the island had fared.

There really wasn’t much to report on in Buxton, Frisco and Hatteras. There was sound water on N.C.12 and there were indicators that the water levels in Frisco were about 2 to 3 feet high.

The high-water mark on my business building in Frisco was about the same as Hurricane Earl in 2011. Parts of Brigands’ Bay were still underwater and not passable. Further south, we traveled through the area where Hurricane Isabel had cut through Highway 12 in 2003, and the dunes didn’t completely hold. The road was passable with four-wheel drive, and as the road crews quickly worked to clear the sand, it was evident that the road surface was mostly unaffected.

Feeling like we had escaped the big one, we visited a friend in Hatteras who sat out in his yard reading his Bible and talking about the beautiful blue sky. In a moment of thankfulness, we reveled in our luck. With all the technology in the world, we sat alone on our island in bliss — unconnected, totally unaware how bad our neighbors in Avon, Waves, Salvo and Rodanthe had it.

We worked our way back to the north and saw that Buxton had its usual post hurricane problems and at first glance, the most noticeable damage in Avon was the blown over canopy at the BP Station at Askins Creek. However, news of the inlets was spreading and we wanted to investigate.

The National Guard arrived on Aug. 28 at the Hatteras Island Rescue Squad in Buxton. Photo: Don Bowers, Island Free Press |

We drove a little north of Avon on a road that was too sandy and still underwater. Our gas tank was low, so we opted to go home and start fresh in the morning. At some point, we turned on the radio to a local station and learned lots from Dare County residents who called in with their eyewitness reports.

We were close to home when we saw something that stopped us in our tracks. The National Guard had arrived in great numbers and was unloading supplies at the Hatteras Island Rescue Squad in Buxton. Seeing the large group of men and women in military uniform moving large amounts of food and water, tarps, and medical supplies, was our first personal experience in how bad the situation was. A quick interview with incident commander Bob Helle confirmed it.

The northern villages were hardest hit and would receive the majority of the supplies. N.C. 2 was completely impassable and an emergency ferry would start bringing supplies from Stumpy Point into Rodanthe. Transportation on and off the island was not possible and an emergency medical team was flown in to help islanders since our local doctors were unable to get back on the island.

In that moment, everything changed as I realized again that this was no ordinary hurricane. It would be a long time before life would be back to normal. There would be no reason to reopen my business, even though there was very little damage done to the building.

Donny went home to work on his pictures with the help of our generator while I visited Irene Nolan at her house to report what I knew. We developed a plan to cover the storm. With no communications on the island, it was important to do our best to report what we knew. Without electricity, it may not be read by people who didn’t evacuate, but it was important for those who left to know how the island was doing from people who stayed.

I went home and my little laptop worked well off the generator. I wrote a short article about what I had seen during the day and what I heard from Bob Helle. We finished our work by midnight and drove to Buxton to the Cape Hatteras Electric Cooperative that miraculously had a working wi-fi signal. In the dark parking lot and in the cool comfort of my truck, I e-mailed my unedited story and Donny’s pictures to Donna Barnett, Island Free Press graphic designer and webmaster, who had evacuated to Raleigh, N.C., with her computer so she could keep the news going. This is how the newspaper published articles for the first few days directly following the storm.

At sunrise, Donny and I were standing by the breach at Mirlo Beach in Rodanthe. This is where we would spend the next few weeks.