HOLLY RIDGE – Groups like the N.C. Coastal Federation spend a lot of time and effort building oyster reefs to create marine habitat and improve water quality. But do the reefs really work? Do the lifeless piles of shells actually become a sort of living organism? Are the marshes that the reefs protect thriving?

Federation volunteers set out last month to find out. They measured the salt marsh that the federation built at its Morris Landing Preserve in Onslow Countyand poked around the reef for signs of life. The reef is an ongoing federation project, and the group monitors it as it does all its oyster restoration projects.The results so far are very encouraging.

Supporter Spotlight

Worms and other marine life begin to colonize an oyster shell on the sill. Photo: Gregory Loftis. |

“The projects are looking generally successful,” said Ted Wilgis, a federation educator and head reef builder. “So far we haven’t had any failures.”

Erosion constantly threatens the marshes of our coast, forcing them to retreat inland. Wooden bulkheads and stone walls meant to combat erosion also prevent the marshes from migrating. Slowly, they disappear as the shoreline in front of the wall continued to erode. Living shoreline projects like the Morris Landing oyster sill offer an alternative to walls, but it’s important to keep an eye on them to see if the they are working, Wilgis said. One way is to sample for marine life.

“A successful oyster sill,” Wilgis said, “will have new, live oysters attaching and growing around it.”

Volunteers checked each individual oyster shell from several submerged bags for signs of life. Because the newest section of the sill at Morris Landing has only been in place since November, no full-grown oysters were found in this survey. However, spats – baby oysters – covered the reef, as well as other marine life such as worms, snapping shrimp and sea squirts. They’re early indicators of a successful sill, Wilgis said.

Coastal vegetation is another metric used to determine the effect of a sill. Volunteers measured the height and density of the salt marsh hay and cordgrass at Morris Landing. The information will be compared against previous surveys to determine whether the marsh grew.

Supporter Spotlight

The marshlands aren’t the only thing the federation hopes to protect. “We’re trying to encourage oysters to spawn,” said Wilgis.

Oyster reefs provide habitat for many smaller marine species. Whenever a new oyster sill is put into place, Wilgis always hopes it will attract baby oysters and eventually become home and hunting ground for many other animals.

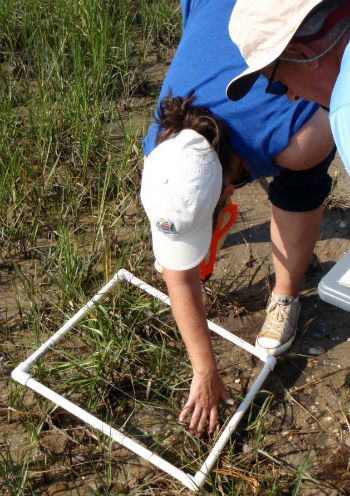

Volunteers and members of the federation measure the height of marsh grass. Photo: Gregory Loftis.

But the sills have to be carefully monitored to make sure they’re fulfilling their intended purpose.

“The sills have to be constructed correctly,” says Rachel Gittman, a researcher at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill who is studying coastal restorationprojectss. “Sometimes, an area doesn’t even need a sill.”

Gittman said that the federation’s efforts have all been appropriate and well-constructed, but other organizations and private landowners have made poor decisions. “Some places have been installed with unnecessary sills,” she said, “and they actually get in the way.”

Bree Kerwin and Frank Headly measure the density of the marsh grass. |

There are alternatives to oyster sills in areas where erosion is not such an immediate threat, Gittman explained. Simply replanting and filling the already eroded shoreline may be sufficient. There is no easy, cure-all solution, she noted.

“Lack of awareness and education [about coastal protection] has been one of the major obstacles,” Gittman says, “but I think people are starting to become more aware of the problems facing our coast, and how it might affect us.”

The federation will continue to monitor Morris Landing over the coming years along with other projects, such as Permuda Island in Stump Sound and Jones Island in the White Oak River. Future plans include a 200-foot living shoreline at Oak Island.

It’s important to work scientifically to maximize the effectiveness of habitat restoration projects, Wilgis said. As the data from monitoring habitat restoration projects comes in, the federation will adapt its strategies, he noted.