With state legislators still wading through the issue of rising seas, a new federal report released yesterday seems to further muddy the water.

Contrary to what we heard from some legislators the last few weeks, not only does the sea seem to be rising along the state’s northern coast, but it’s doing so at a rate three or four times faster than anyplace else in the world.

Supporter Spotlight

That, at least, is one of the conclusions of a new study of sea-level rise that the U.S. Geological Survey published yesterday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Analyzing information from tide gauges along the north and mid-Atlantic coasts, agency researchers found that sea level along a 600-mile stretch, from Cape Hatteras to north of Boston, has increased 2 to 3.7 millimeters a year, starting around 1990. That’s as much as 2.75 inches during that span. The average global increase over the same period was 0.6 to 1.0 mm. a year, or about three-quarters of an inch total, the study notes.

Peter Howd |

If global temperatures continue to increase this century because of global warming, the Atlantic Ocean in this region is expected to continue to rise at a faster rate than it will elsewhere, the researchers said. The sea along this stretch of coast, which contains some of the country’s largest metropolitan areas and densest coastal landscapes, could rise 8 to more than 11 inches higher than the global average by 2100, the research showed.

It’s not just a faster rate, but at a faster pace, like a car on a highway “jamming on the accelerator,” Asbury Sallenger Jr., an oceanographer at the agency and the study’s lead author, told the Associated Press.

Seas will rise gradually over time, noted Peter Howd, an oceanographer under contract with the USGS and one of the paper’s other authors, but greater flooding from winter storms will be the first signs.

Supporter Spotlight

“People are starting to recognize that winter storms that used to pass by without producing any flooding, all of sudden they are getting flooding,” Howd said in an interview last week. “Where it’s really going to hit home is that the storms that we get 3 or 4 times a winter will start looking like the storms that we get every 3 or 4 years.”

Science and Politics

The new research seems to counter arguments made by backers of a bill that passed the N.C. Senate a couple of weeks ago. The bill was widely interpreted as preventing the state from using the latest scientific modeling when planning for future sea-level rise because of global warming.

Warming atmospheric temperatures in the future are expected to push up sea levels by melting ice sheets in Greenland and west Antarctica, and because warmer water expands. Climatologists use sophisticated computer models to predict how high the seas could get under different warming scenarios.

After reviewing the consensus of those models, a panel of scientific advisors told the state Coastal Resources Commission in 2010 to prepare for a sea-level rise of 39 inches by 2100, or more than triple the historic rate. Though the new research suggests adding a few more inches to that total, the forecast was in line with those made by major scientific organizations around the world and by several countries and other states.

But the state report immediately came under fire from development interests and some coastal counties. They feared that regulations to protect against such a drastic rise in sea level would stifle economic growth on the coast.

Critics also questioned the science behind the state report. That was echoed by sponsors of the Senate bill. The science of sea-level rise was unsettled, they said, and the models were speculative at best. Credible evidence exists, they noted, that indicates sea levels haven’t risen appreciably in the past 100 years.

The bill that passed the Senate would have forced the state to use those historic rates when planning for what the ocean might do in the future. Those long-term average rates of historic sea-level rise, when extrapolated into the future, indicate the ocean might rise only 8 inches this century, not 39.

After being lampooned by commentators, scientists and writers around the world, the bill died last week when the N.C. House refused to vote on it. Representatives from both chambers are trying to devise a compromise.

The names of Robert Dean and James Houston came up often in the debate. They are well-respected coastal engineers who studied data from tide gauges and determined that long-term average sea-level rise for the past 80 years has been negligible even though temperatures have risen.

The USGS researchers tried to replicate Dean and Houston’s findings by using the same tide information from across North America, Howd noted. To determine if the rate of rise has recently accelerated, though, they analyzed smaller time segments of tide gauge data and in a way that removed long-term trends associated with vertical land movements.

“Dean’s numbers are correct for what he calculated, the long-term average acceleration over the last 80 years,” Howd explained. “That’s a very different answer as to whether there’s any recent acceleration. We just asked a different question.”

AMOC and You

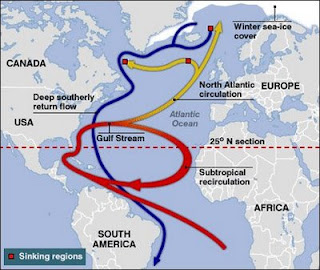

This is the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, or AMOC.This great conveyor belt could be affected by global warming, causing among other things rising seas along the northern N.C. coast. |

The answer they got has everything to do with the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, called AMOC by those who study such things. It’s part of the oceans’ conveyor system, which constantly redistributes heat and cold. AMOC carries warm water from the tropics to high northern latitudes near the surface and returns cold water from the north Atlantic in the deep ocean to the Southern Hemisphere. In that way, a balance is achieved. The Gulf Stream is AMOC’s main highway north.

How AMOC does all this is complicated, involving water temperature, salinity and density in the subpolar north Atlantic, but scientists have long thought that a warming climate could affect the circulation. The USGS study, though, may be the first to indicate that might be happening already. The report shows that the sea-level rise “hotspot” north of Cape Hatteras is consistent with the slowing of AMOC, Howd said.

So much water is flowing north in the Gulf Stream and at such a quick pace that the core of the stream is two meters higher than the water at the shoreline, Howd explained. “When the current slows down, the Gulf Stream falls and the water levels increase at the coast. That’s the simple answer, but it’s pretty complicated.”

The magnitude of this see-saw affect will be greater farther from the Gulf Stream, Howd said. The Stream hugs the N.C. coast before veering east across the Atlantic north of Cape Hatteras. Howd and the other researchers saw no evidence of accelerated sea-level rise above the global average for much of the state’s coast. It became evident north of the cape, he said, but the rate there was lower than it was farther north.

Because of its proximity to the Gulf Stream, the northern N.C. coast could expect to see seas rise at the low end of the study’s estimates, about 8 inches above the global average by 2100, Howd said.

Whatever the they do in the future, the oceans won’t do it at the same rate in every location, noted Marcia McNutt, the director of the USGS. Differences in land movements, strength of ocean currents, water temperatures and salinity can cause regional and local highs and lows in sea level.

“Many people mistakenly think that the rate of sea-level rise is the same everywhere as glaciers and ice caps melt, increasing the volume of ocean water, but other effects can be as large or larger than the so-called ‘eustatic’ rise,” she said. “As demonstrated in this study, regional oceanographic contributions must be taken into account in planning for what happens to coastal property.”

And it may not take years to feel the effects of rising seas, Sallenger said.

“Cities in the hotspot, like Norfolk, New York and Boston already experience damaging floods during relatively low-intensity storms,” he said in a press release. “Ongoing accelerated sea-level rise in the hotspot will make coastal cities and surrounding areas increasingly vulnerable to flooding by adding to the height that storm surge and breaking waves reach on the coast.”