WILMINGTON — Margaret Herring, federation volunteer and self-proclaimed “creek keeper,” has been an activist for most of her life. When she retired from her career as a school teacher and came to Wilmington at the turn of the century, Herring became involved, first, with Cape Fear River Watch programs and in then 2003, at the age of 66, with the federation.

“I had an aunt who would take me outside and talk about the trees and nature,” she said, “I’ve always loved the outdoors and liked taking care of it, so it came naturally.”

Supporter Spotlight

Living on Riley’s Branch of Hewlett’s Creek, she learned from Ted Wilgis, a federation educator, and from training as a former Coastkeeper volunteer all about the stormwater that flowed by her property to the ocean.

Margaret Herring |

“It was a wonderful training program,” she said. “It really raised my consciousness about stormwater and the impact it has on the environment.”

She is characteristically modest about her contributions as a federation volunteer, noting that “basically, I pick the trash up out of the drain near my house.”

Wilgis is more expansive. “She helps with restoration and advocacy, and took the bus up to Raleigh to lobby,” he said. “She doesn’t do a ton of stuff, but she is dedicated.”

Dedication is just one of the things that Herring brings to the table as a Federation volunteer. She also brings a few hard-earned lessons from a long history of political and social activism.

Supporter Spotlight

“We have to work together to take care of (the coastal environment), so everyone can survive,” she said. “I learned about working together and about political power in the civil rights movement.”

The lessons almost got her killed.

Born in 1936 in Ashland, Ky., Herring moved as a baby to Winston-Salem, where she attended R.J. Reynolds High School and went on to study liberal arts at Wake Forest College. Married and with two children, Herring was living in the Washington area in 1962 when she began working as a secretary and assistant to Drew Pearson, the famed syndicated newspaper columnist.

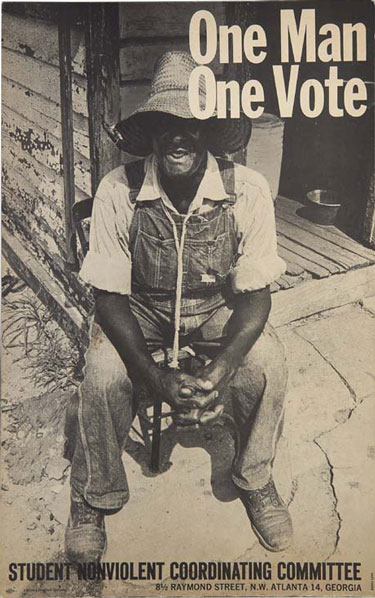

The One Man One Vote campaign in the 1960s swelled voters rolls in the South with African-Americans. |

“We were very close friends,” she said of the professional relationship that lasted about two years. “My job, basically, was to open his fan mail and answer it, and I’d type up his columns and his diary.

“We kept getting press releases from civil rights organizations about people trying to register voters in the Deep South,” she added, “and about how they were being beaten or killed.”

In the summer of 1964, Pearson brought Herring along to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, N.J., where the party would eventually nominate President Lyndon Johnson for re-election. A variety of civil rights organizations were also there, demonstrating outside the hall.

Pearson sent Herring to the Gem Hotel to interview representatives. She spoke with members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which had been created in 1964, with assistance from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), to challenge the legitimacy of the white-only Democratic Party and seat black members at the convention. It was a challenge that failed, initially, but it served to dramatize the injustice experienced by disenfranchised blacks. It was, according to SNCC Chairman John Lewis in Wikipedia, a “turning point in the civil rights movement.”

“Our community (in Winston-Salem) was very segregated when I was growing up, so I had seen all of this first-hand, and it didn’t make any sense to me why they were treated that way,” she said. “My father was a Baptist preacher and a well-educated Greek scholar, so all that and the things that Jesus said, just made that sort of behavior a huge contradiction for me.”

It was enough of a contradiction to make Herring quit her job with Pearson, leave her children with her husband in Washington and head to Mississippi and then eventually to SNCC headquarters in Atlanta.

In Mississippi, Herring helped gain support for the students by calling press in the North, friends of SNCC and local police stations. SNCC had programs in Alabama, Georgia, and Arkansas, and it was Herring’s job to try to acquire as much financial and human assistance for the organization as possible.

“There was an opportunity to be a part of it and I knew it would pass, that it wouldn’t last forever,” said Herring. “If I didn’t go then, I knew I’d never have the chance to do something about injustice.

“I guess it gets in your blood,” she added.

But when a new era of the civil rights movement emerged in 1966, she turned the reins over to those whom she considered their rightful owners. The concept of Black Power became prevalent and Herring responded to the calls made by activists like Stokely Carmichael for a stronger, more African-American led force.

Herring left the SNCC, took a year off and met her second husband. She then was off to eastern Kentucky to work with poor whites and to combat high poverty rates, unemployment, poor schools and infrastructure. Coal companies there had exploited their workers and polluted the environment by strip-mining, and they didn’t much like outsiders coming in to stir up trouble

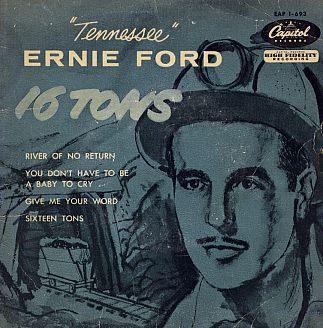

Ernie Ford scored an unexpected hit in 1955 with his rendition of Merle Travis’ “Sixteen Tons,” a coal-miner’s lament that Travis wrote in 1946, based on his own family’s experience in the Kentucky mines. Its fatalistic tone contrasted vividly with the sugary pop ballads and rock & roll just starting to dominate the charts at the time:“You load sixteen tons, what do you get? Another day older and deeper in debt. Saint Peter, don’t you call me, ’cause I can’t go; I owe my soul to the company store…” |

Herring and her husband moved to Pike County, Ky, in 1967, where opposition to their activities got ugly. In August of that year, their home was raided by 17 armed men and they were arrested and jailed for sedition. Herring was pregnant at the time.

Seized in the raid were hundreds of documents, purported to be evidence of seditious behavior. Copies were made and forwarded to U.S. Sen. John McClellan and his Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, a remnant of Sen. Joe McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. When the couple refused to give up the originals, they were charged with contempt of Congress.

Herring and her husband were released on bond, and Herring soon gave birth to a son.

In the middle of the night during the unusually cold winter of 1968, her home was bombed. In the “darkness and swirling dust” of the explosions, with a crying baby and her husband “crawling around looking for his clothes,” Herring managed to call the Kentucky State Police, who found evidence that six sticks of dynamite had been thrown against their bedroom window. They left Pikeville that night.

It took 18 years for the criminal and civil court lawsuits filed against McClellan and his committee to resolve themselves. When they did, in 1982, Herring had some money to pay for a college education. She earned a master’s degree in international education from American University and eventually taught English as a second language. She retired in 2000.

“I was very, very tired,” she said of her decision to retire, “and it was time.”

Ancestors on her father’s side of the family had run a farm in Pender County, so Herring was familiar with the Wilmington area. It has numerous amenities that interest her: theater — she ushers at the Red Barn Theater occasionally — a university, and, of course, the beach.

So here she is in 2012, advocating for the environment of her adopted home and continuing to apply lessons learned the hard way.

“You can’t,” she’ll tell you, “just stand by when you see injustice.”

Editor’s Note: If you want to read more about Margaret Herring, see In Our Defense by Ellen Alderman and Caroline Kennedy (Morrow), Freedom Spent by Richard Harris (Little, Brown), Night Comes to the Cumberlands by Harry Caudill (Jesse Stewart Foundation), and It Did Happen Here, by Bud and Ruth Schultz (University of California Press).