First of two parts

|

RALEIGH — Fish caught in Eastern North Carolina have contained some of the highest levels of mercury in the nation. That poses a threat to people who eat them.

Supporter Spotlight

State environmental officials say the state needs to reduce mercury levels by 67 percent by 2016 to protect North Carolina’s waters from mercury contamination, make fish safe to eat and ultimately lift the fish consumption advisories.

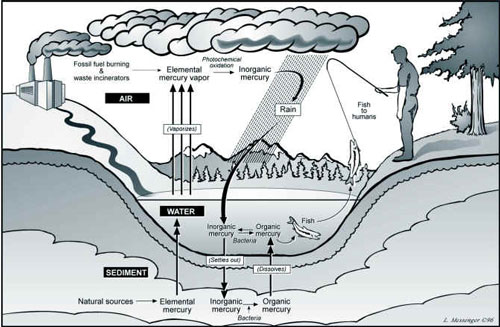

Mercury is a potent neurotoxin and reduction efforts are already underway. Unfortunately much of the mercury that contaminates the state’s rivers, lakes and coastal waters comes from power plants and sources in other states and even other countries, state officials say.

“It’s an issue that needs to be addressed,” said Kathy Stecker of the N.C. Division of Water Quality. “It’s a global problem. It’s not just a North Carolina problem. But that doesn’t mean we can’t start to work on it.”

The state currently lists all water bodies in the state as contaminated by mercury. The N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources is drafting a plan to quantify sources of mercury such as power plants and sewage treatment plants and propose steps to reduce mercury in North Carolina waterways. Having such a plan will make it easier to press other states that contribute to North Carolina’s pollution problem to cut mercury pollution, officials say.

As part of the process, state officials are developing an estimate of the maximum daily amount of mercury that waters may absorb without contaminating fish and posing a threat to humans. It’s known as a total maximum daily load, or TMDL, and it sets a target for reducing mercury. A public meeting is scheduled Wednesday in New Bern on the plan.

Supporter Spotlight

Coast Most Affected

New Bern MeetingPeople are invited to hear about the mercury reduction plan, ask questions and offer input at a public meeting from 1-3 p.m., Wednesday at the Craven Cooperative Extension Building in New Bern. |

Mercury contamination varies greatly across the state. Mercury concentrations in fish tend to be higher in coastal North Carolina than in the mountains or piedmont areas of the state, according to environmental officials and researchers.

“We see in Eastern North Carolina some of the highest mercury levels in the nation,” said Derek Aday, an ecologist at N.C State University who has done research on mercury deposition and affected fish. “It’s really variable from water system to system.”

Aday said the eastern portion of the state tends to have swamps and peaty, acidic soils that promote the formation of methylmercury, the toxic form that can build up in the tissue of fish and wildlife.

People in coastal North Carolina are exposed to mercury primarily by eating fish that contain methylmercury, a neurotoxin and can damage developing fetuses. Statewide health advisories warn about limiting consumption or avoiding certain species of freshwater and ocean fish that commonly have high levels of mercury.

The advisories warn that women of childbearing age, pregnant women and nursing mothers should avoid eating certain types of fish known to be high in mercury. Other people should limit consumption of these types of fish to no more than one meal a week.

Fish species vary greatly in the amounts of mercury they contain. The amount of mercury in fish depends on what the fish eat and how long they live. As a rule of thumb, longer-lived and larger predator fish, which devour smaller fish, typically accumulate higher levels of mercury in their tissues. Among saltwater fish listed as high in mercury are cobia, grouper, gag, king mackerel, greater amberjack, orange roughy, Spanish mackerel, shark, swordfish and albacore tuna.

Fish With High Levels

In recently published research, Aday and colleagues tested mercury levels in six commonly consumed fish caught by commercial and recreational fishermen in North Carolina. They found that king mackerel had the highest mercury concentrations. Grouper and wahoo also had high levels, while mahi mahi and triggerfish had the lowest levels.

Tests also have revealed high levels of mercury in freshwater fish such as black crappie caught east of Interstate 95 and in blackfish, catfish, chain pickerel and yellow fish caught east of Interstate 85, according to N.C. Department of Health and Human Services.

Tests also have revealed high levels of mercury in freshwater fish such as black crappie caught east of Interstate 95 and in blackfish, catfish, chain pickerel and yellow fish caught east of Interstate 85, according to N.C. Department of Health and Human Services.

While largemouth bass caught throughout North Carolina have shown high levels of mercury, most of the high mercury concentrations occur in the eastern part of the state in the Cape Fear, Pasquotank, Lumber and Tar-Pamlico river basins. The highest mercury concentrations have been found in largemouth bass in the Lumber River basin.

If the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency approves the state’s mercury reduction plan, it could affect private industries that operate their own wastewater treatment plants —some of which have high levels of mercury in treated wastewater. They would be required to develop plans to minimize the discharge of mercury. But wastewater plants represent only about 2 percent of the overall mercury released in the state.

“There seems to be some kind of misunderstanding that we are only targeting wastewater plants,” Stecker said. “The reduction we are looking for is the same reduction as from the other source we identify. We are not asking them to get any more of a reduction than their fair share. “

Coal Burning and Mercury

Most of the mercury getting into the water and fish comes from airborne emissions. When power plants burn coal to generate electricity, the combustion releases mercury into the air. Coal-burning power plants are the largest source of mercury in the United States, according to the EPA. They account for more than half of mercury emissions.

Mercury in the air eventually settles into bodies of water or on land, where rain can wash it into the water. Microorganisms in the soil convert the mercury into methylmercury, a toxic form that builds up in fish and shellfish.

According to the state, power plants, steel mills and incinerators spewed approximately 5,300 pounds of mercury into the air in North Carolina in 2002, a year used as a baseline for measuring mercury. Two-thirds of the mercury came from coal-burning power plants operated by Duke Energy and Progress Energy.

Coal-fired power plants are the largest source of man-made mercury in the United States. |

Since then, mercury emissions have dropped dramatically, according to the state. In 2002, state lawmakers approved a significant environmental bill known as the Clean Smokestack Act, which required utilities to make significant reductions in certain air pollutants by 2016. The scrubbing of certain pollutants from smokestack emissions at larger power plants had the added benefits of reducing mercury releases. Mercury emissions from power plants dropped from 3,500 pounds a year in 2002 to 963 pounds in 2010, according to state data. By 2016, mercury emissions from power plants are projected to drop by 72 percent.

Tom Mather, a spokesman for the N.C. Division of Air Quality, said the state anticipates additional reductions in mercury from the closure of some smaller coal burning plants and tighter federal regulations on industrial boilers. Mather said state computer estimates that only 16 percent of the mercury in the state comes from power plants and factories within the state. Most of the airborne mercury wafts into the state on wind currents blown from other states and even other countries.

“We’ve done a lot to reduce mercury emissions in North Carolina, and we expect further reductions,” Mather said. “But there is only so much we can do here if only 16 percent of our mercury is coming from sources within North Carolina.”

The Division of Air Quality has drawn up a list of options for achieving additional cuts in mercury air emissions. They include:

- Filing a legal petition to seek reductions in mercury emission from utilities outside North Carolina

- Setting a cap on statewide mercury emissions

- Reviewing industrial facilities’ pollution control technologies that would increase mercury emissions on a case-by-case basis

Tuesday: The role of the ecosystem’s smallest creatures