Second of two parts

“Where you from?”

Supporter Spotlight

Marc Basnight, a retired N.C. senator and once the state’s most powerful politician, pulled up next to an SUV parked at Jennette’s Pier in Nags Head, where a man was dumping sand out of his shoes.

The man looked surprised. “Maryland,” he said.

“How do you like our pier?”

The new cement structure stood high above the curling blue surf. For Basnight, who had craftily maneuvered for N.C. Aquarium funds to buy and later rebuild the old pier, the visitor’s endorsement was almost a personal matter. But the man hadn’t yet been on the pier.

“Well, enjoy it when you do,” Basnight said.

Supporter Spotlight

With a frown, he turned his attention to the ocean. “Look,” he said, indicating five imposing ships within a mile of shore.

They were factory fishing ships from the Chesapeake Bay seeking menhaden. “That shouldn’t be allowed so close to shore,” Basnight said. “I thought I had taken care of that. I thought they were supposed to stay offshore.”

But he hadn’t quite taken care of it. A call later confirmed that menhaden boats were allowed within a half mile of the beach in the winter. If those regulations were to be changed, someone else would now have to do it.

Basnight’s retirement from the N.C. Senate in 2010 followed the Republican takeover of the N.C. General Assembly and the loss of his hold on power as the Senate’s president pro tempore. While the Manteo resident remains a force in politics—Basnight is highly influential with Democratic office holders like his protégés Gov. Bev Perdue and U.S. Senator Kay Hagan—the shift has left the coast with a much diminished presence in Raleigh.

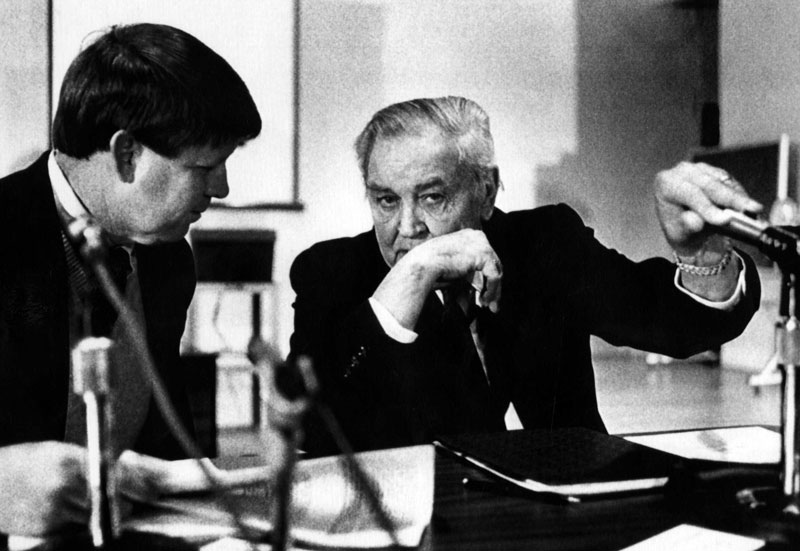

U.S. Rep. Walter Jones, D-N.C., (right) and N.C. Sen. Marc Basnight hold an impromptu discussion before the beginning of a 1989 public hearing at Manteo High School on offshore drilling. Photo courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center.

A Rising Star

But in the early 1990s, Basnight’s star was still on the ascent.

As chairman of the Appropriations Committee he was a favorite of then-President Pro Tempore Henson Barnes. The president’s post had recently acquired new significance. When Republican Jim Gardner was elected lieutenant governor in 1988, the Democratic majority in the Senate swiftly transferred much of the powers held by that office to the leader of their own chamber. Suddenly, Barnes rather than Gardner had final say over the budget, assignments to legislative committees and appointments to state boards and commissions.

In 1993 when Barnes announced his retirement, Basnight quickly made a bid for the president’s post. He called in favors and consolidated his support with impressive speed.

“He understood the way power works and the way personalities work,” said Tony Rand, a former Democratic state senator and close Basnight colleague. “Marc is a natural leader. You don’t ascend to a role like that unless people are willing to go down the road with you.”

Basnight swiftly started moving his pet projects through the chamber. Frequently these included his own ideas, gleaned from his voracious reading. On more than one occasion he forgot to tell his staff before announcing his latest grand plan.

In 1996 Basnight was invited to give an Earth Day address at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Invoking images from a huge fish kill that had plagued the Neuse River the previous summer, he announced the creation of a new source of money, the N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund, to be used to stem pollution in waterways across the state.

“He had even figured out a way to pay for it,” remembers Bill Holman, an environmental lobbyist at the time who is now director of state policy for the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University.

People started calling Norma Mills, Basnight’s chief of staff, wanting to know more about the proposal. “But she knew nothing about it,” Holman remembered.

The trust fund became one of Basnight’s most cherished legacies to conservation. Since its inception in 1996, the fund has distributed about $970 million in more than 1,500 grants. The money has been used to buy sensitive lands threatened by development, clean up hog lagoons, improve sewer plants and reduce stormwater runoff. It also bankrolled major planning initiatives, including a blueprint for restoring the state’s once-great oyster population.

The fund was so closely associated with Basnight that Republicans in the House “would take it hostage in the budget to get Marc to do something they wanted,” said David Rice, a former reporter for the Winston-Salem Journal who covered the N.C. General Assembly for 13 years.

Basnight’s contributions to stemming pollution also included his shepherding of the 1997 Clean Water Responsibility Act, which tightened regulations on hog farms and municipal sewage treatment plants.

Wielding Power

Sen. Marc Basnight (right) and Dean Louis Martin-Vega of N.C. State University’s College of Engineering look out at new engineering building. Basnight was strong support of North Carolina’s university system. NCSU photo.

He deftly wielded political capital, dispensing favors to those who earned them while sometimes punishing others. Rice recalled an incident when Basnight was trying to obtain state funds for a satellite campus in Dare County for the N.C. School of the Arts. Sen. Billy Creech, a Republican from Johnston County, facetiously called the project “UNC-B.” Rice quoted Creech in an article.

When Creech saw the published quote, “he pushed back in his chair and got real quiet,” Rice said. “Then he said, ‘Well, I didn’t want to get anything (in the budget) this year anyway.’”

Rice recalled that Basnight loved to joke with his colleagues and reporters, and that his jokes were often too racy to be repeated. Tony Rand, the Senate’s majority leader from 2001 to 2009, also spoke fondly of Basnight’s playful side. “We had fun, oh we had fun,” he said. But when asked to give an example, he demurred.

The fun could turn off in an instant when Basnight grew displeased. Legislative insiders tell of state employees being bullied into changing their positions on sensitive issues. And, they note, Basnight’s temper was legendary. Some used names to refer to Basnight that were not always meant to be flattering — The Boss, The King and The Squire of Manteo.

Basnight also amassed a huge campaign war chest, much of it from business interests.

It was inevitable that inland legislators began to resent the state funds flowing to the coast for special projects — The David Stick Library at the Outer Banks History Center, Roanoke Island Festival Park, Jennette’s Pier. And environmentalists bristled at the ease with which developers in Basnight’s district could grease the skids for pending permits simply by calling Basnight’s office.

In a 1995 editorial headlined “Basnight’s Lofty View,” the Raleigh News & Observer wrote that the senate president had “flirted with crossing the line” with too much arm twisting. The column cited Basnight’s interference with fisheries management issues and his diversion of $700,000 from an account in the state Department of Cultural Resources so it could be used to develop the Elizabeth II historic site at Festival Park in Manteo. “To be fair,” the editorial added, “Basnight has also been a champion of open government.”

As his terms as senate president stacked up year after year —an unprecedented run in state history—the criticisms and jealousies mounted. U.S. 64, the road between Raleigh and Manteo, was dubbed “Basnight’s Driveway” by some of his critics. It was raised and widened, while busier coastal roads like U.S. 17 remained narrow and congested.

“I never minded getting beat up in print,” Basnight insisted. “I say bring it on. Free speech is one of the greatest things in this country. Let freedom ring.”

America’s founders—Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, John Adams and others— savaged each other “in pen and print,” he said. “It’s all part of the process. The truth will come out.”

Personal Trials

In 2002 Basnight suffered the first of a string of personal trials when his wife, Sandy, was diagnosed with cancer. He responded by seeking the best treatment for her—and in the process funneled $180 million to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for a cancer hospital and imaging center. That initial funding was followed by a recurring $50 million annual appropriation from the legislature despite tight state budgets and is making North Carolina a leader in cancer treatment.

Marc Basnight and his late wife, Sandy. AP Photo.

“The origin of it was his wife’s disease,” said Rice, “but its implications reach out to the one in three of us who will have that disease.”

Perhaps the most lasting of Basnight’s legacies will be his support of the state university system. In 2000 he was the driving force behind a $3.1 billion bond initiative for higher education, including community colleges. The bond was approved by 70 percent of the voters. He also funneled budget allocations into university research program.

Reflecting on his legislative legacy, Basnight mused, “We did a lot of good things with the universities, but with the environment too—in ways you wouldn’t even hear about.” He mentioned pushing the N.C. Department of Environmental and Natural Resources staff to clean up Swift Creek, one of the most polluted waterways in the state.

With a mischievous smile, he also told of replacing all the lights in both state Senate and House chambers with energy-efficient bulbs.

“They said the new light bulbs would cause headaches. I put them in and they never knew the difference.

“Everything we did, if it wasn’t going to make the world a better place, we knew it wasn’t worth doing.”

Through the years Basnight became an ally of N.C. Coastal Federation, which he said he admired because of its reasoned approach to conservation, emphasis on stormwater control and strong stance against beach hardening.

In 2003 the Coastal Resources Commission granted a variance to the state’s long-standing regulatory ban against seawalls and other types of erosion-control structures on the beach to allow the installation of sheet pilings along N.C. 12 in Kitty Hawk. The road was in danger of collapsing into the ocean. Basnight responded by shepherding through a bill that gave the ban against beach hardening the full weight of the law. However, the federation and other conservation groups were disappointed a few years later when a Basnight-led Senate passed a bill to weaken the so-called seawall ban to allow small jetties on the beach.

Jennette’s Pier in Nags Head undergoes construction. Marc Basnight maneuvered for N.C. Aquarium funds to buy and rebuild the old pier.

Basnight also began pushing for the use of stormwater controls like cisterns and rain gardens on state property. He installed stormwater controls at his restaurant.

Fire the destroyed the Lone Cedar Café in May 2007. To everyone’s shock, the State Bureau of Investigation ruled the cause as arson, but no arrest was ever made.

Although he no longer visits with diners at the rebuilt Lone Cedar, Basnight spends time there overseeing changes to the waterfront, which includes an ever-expanding array of conservation features.

A month after the fire, Sandy Basnight lost her five-year battle with cancer.

Disease Strikes

Two weeks later, Rand said, Basnight fell for the first time. “(He) just toppled over face first. It’s his equilibrium,” Rand said.

Within a short period he fell twice more.

Doctors at first diagnosed a Parkinson-like nerve disease. His speech began to slow and slur, but initially he was able to adapt it to his folksy style of speaking.

After Republicans took over the Senate in the 2010 elections, Basnight lost his leadership position and would have had to go back to debating legislation on the floor. He said he had neither the necessary quickness of speech nor the strength for long stints on his feet.

In his resignation letter in January 2011, Basnight cited an additional reason for coming home: He was newly in love with Manteo resident Sue Waters, a teacher and musician.

Basnight is philosophical about having amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, a degenerative disease of the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord that control voluntary muscle movement. Motor neurons reach from the brain to the spinal cord and from the spinal cord to the muscles throughout the body. The progressive degeneration of the neurons eventually leads to their death. When the motor neurons die, the brain loses its ability to initiate and control muscle movement. With voluntary muscle action progressively affected, patients in the later stages of the disease may become totally paralyzed and unable to breath on their own. While there is no known cure or a treatment that halts or reverses ALS, some drugs can slow the progression and several others show promise in clinical trials.

In this county, the disease gets its more popular name from Lou Gehrig, a Hall of Fame baseball player for the N.Y. Yankees. He brought national and international attention to the disease when he abruptly retired from baseball after being diagnosed with ALS in 1939. He died two years later. Other notable people who have had ALS include Jim “Catfish” Hunter, a Hall of Fame pitcher from Hertford; Sen. Jacob Javits; actors Michael Zaslow and David Niven; boxing champion Ezzard Charles; jazz musician Charles Mingus; and Henry Wallace, a former vice president.

“There’s nothing so special about me that I shouldn’t have this disease,” Basnight said.

He is pursuing all treatments, as he urged Sandy to do with her cancer. Recently he had seen a new doctor in Charlotte, who he said offered him hope. “We’ve been once and we’re going back.”

His public role may be gone, but his charm remains—as does his colleagues’ and constituents’ regard for him.

“Politics make some people grow and some people swell,” Tony Rand said. “Marc never swelled.”

Sign a Petition to Help ALS Patients

Ed Johnson, a longtime federation member who owns a bike shop in Cedar Point in Carteret County, also has been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

He notes that more than 40 treatments are now undergoing FDA trials and that there is great hope for every ALS patient.

Patients and their caregivers have started a Facebook page and are circulating a petition asking the FDA to make promising drugs more quickly available.

Coming Feb. 20: A profile of Sen. Harry Brown of Onslow County, the Republican majority leader in the state Senate and highest-ranking coastal legislator.