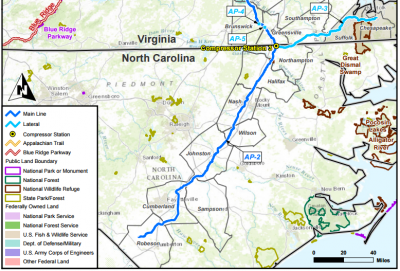

EASTERN NORTH CAROLINA — Thanks to Google Earth, it’s easy to see Eastern North Carolina’s rural versus urban dichotomy in the route of the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Loosely following the path of the Interstate 95 corridor, the pipe would cross 178 miles of mostly small farming communities that suffer struggling economies and limited opportunity. Wealth here is in land, history and culture.

For the most part, the pipeline cutting through Northhampton, Halifax, Nash, Wilson, Johnston, Sampson, Cumberland and Robeson counties bypasses cities, saving urban dwellers from loss of their homes and the hazards of an underground duct carrying volatile gas being installed in their neighborhoods.

Sponsor Spotlight

As political headwinds are shifting back in favor of fossil fuels, opponents of the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline are challenging claims about the safety and economic benefits of natural gas to Eastern North Carolina, pointing to methane leakage and decreased value of property subdivided by pipeline easements.

“There could be environmental impact for the coastal region too,” said Jim Warren, executive director of NC WARN, a nonprofit clean energy watchdog.

“Just the very nature of the state hydrology – it’s not just the large rivers. It’s streams, wetlands.”

Residents throughout the state would stand to be affected by increases of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, he added, as well as potential harm to watersheds, private wells and protected natural resources.

But pipeline proponents say natural gas could bring another kind of riches: jobs, industry and economic growth – all long stagnant or out of reach in the region. Transported 600 miles from West Virginia gas shale through Virginia into North Carolina, the prospect of a plentiful, reliable supply of the fuel has been welcomed by most of the elected officials and business advocates in the eight counties.

Sponsor Spotlight

A collaboration of Duke Energy, Dominion Resources, Piedmont Natural Gas and Virginia Natural Gas, With the proposed $5 billion project, with a 1.5 billion cubic yard per day capacity, if approved, is planned to be in service by late 2019. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, better known as FERC, issued a Draft Environmental Impact Statement in December 2016. Comments on the proposal will be accepted through April 6.

The pipeline would cross into North Carolina at Northampton County near Pleasant Hill and end in Lumberton. Construction could start as soon as Nov. 2017.

John Chaffee, president and CEO of NC East Alliance, a nonprofit economic development advocate serving 28 counties in eastern North Carolina, said that the availability of pressurized natural gas would attract more industry and manufacturing to a region that has long needed an economic shot in the arm. Although there is natural gas available, piped in from the Gulf of Mexico, it has inadequate pressure.

“We’re at the end of the distribution line,” he said, adding that it is not enough to sustain large industry.

Chaffee, a 40-year veteran of economic development in the region, acknowledged that some property owners will be unhappy with the pipe’s location through or near their land, their home or their community. But unfortunately, he said, highways, power plants and other public infrastructure come with tradeoffs.

“The downside is that some people will have their lives disrupted,” he said of the pipeline. “In eastern North Carolina, as a whole, I think the benefits outweigh that.”

According to Dominion, the 2-year construction project would bring nearly $700 million in economic activity to the region and create more than 4,000 good-paying jobs. In addition, the pipeline would bring work for local construction supply and service industries.

In the first 20 years of operation, Dominion projects that the pipeline would generate $1.2 billion in capital investment in the state, save $130 million in annual costs for electric and gas customers and pay a total $28 million annually in property tax revenue to communities.

Another benefit, he said, is that natural gas is cleaner than coal and does not require the massive start-up costs of nuclear. It also does not leave behind toxic coal ash or radioactive waste, respectively.

Chaffee agrees with numerous policy makers who promote natural gas as a “bridge” between dirtier fossil fuels oil such as coal and clean renewable energy such as wind and solar.

“It’s a better complement to renewable energy,” he said. As a backup, it can be turned on quicker than coal-fired or nuclear power plants.

“We support its development,” Chaffee said about renewables. “We think when done properly, in an organized fashion, it’s a very good rural economic development strategy. Wind energy and solar energy provide a boost to those counties’ tax base.”

Still, a growing number of residents and property owners are skeptical about the pipeline. They worry about losing property value from having it divided by easements that restrict building. They worry about compromising sacred ancestral land. They worry about explosions, methane pollution and harm to waterways and animals.

Critics also warn that the amount of natural gas is overestimated, and the pipeline could run dry in the near future. Most of the pipe would be 36-inch diameter, buried under 3 to 5 feet of ground. It would run deeper under streams and railroads.

“They’re attempting to use my property as economic sacrifice for their corporate profits,” said Marvin Winstead, a small farmer and former educator in Nash County. “It would ruin my farm.”

Winstead said he has declined to accept the right of way offer from the utilities, because it would undermine the his future ability to subdivide his land, making it lose considerable value.

“If that pipeline goes across,” he said, “it’s forever locked into farmland.”

But some scientists NC Warn has worked with say there are considerable risks to a natural gas pipeline beyond land use.

“There’s a real uncertainty about the supply of gas over time,” Warren said. “This assumption that this going to be automatically good for North Carolina’s economy needs to be scrutinized.”

David Hughes, a shale gas expert from Canada, said that the amount of underground natural gas that can produced by fracking is exaggerated by 50 percent or more.

Hughes, currently a scientist with the Post Carbon Institute, said that most shale wells dry up quickly.

“If natural gas production declines, as is currently the case,” he said, “and drilling rates cannot be maintained due to poor economics, fuel prices could skyrocket, putting (electricity customers) at risk of shortages and price spikes.”

A Cornell University scientist, Robert Howarth, also disputed the value of natural gas as a “bridge” fuel.

“The problem is that natural gas is composed mostly of methane,” Howarth said in a 2016 video, “and methane is just an incredibly potent greenhouse gas, more than 100 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

“So if we leak a little bit of that methane into the atmosphere when we develop gas, it’s simply disastrous.”

Warren said it would be a different story if more gas power was the only option available. North Carolina has one of the largest commercial solar industries in the nation, and interest is high in land-based commercial wind power.

But the state’s utilities are one of the few in the country that maintain near monopoly-control, he added, and the Republican-controlled legislature has introduced numerous bills attempting to hobble the renewables industries.

Members of the North Carolina Alliance to Protect Our People and The Places We Live, or APPPL, had organized a walk from the Virginia-North Carolina border along the 200 or so miles of the proposed pipeline route to raise awareness about the project. It began March 4 and ended Sunday in Hamlet in Robeson County. The statewide coalition was formed in late 2016 to protest the pipeline.

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline is also a social justice issue, said Ericka Faircloth, Clean Water for North Carolina organizer for water and energy issues. Much of the gas line, she said, runs through historically African-American and indigenous communities.

For instance, the population in Northhampton County, where the pipe enters North Carolina, is 59 percent black, she said, compared with about 22 percent statewide. (The county will also be the site of a gas compressor, which opponents say is vulnerable to methane leaks and explosions.) Halifax County is 50 percent black, and Robeson County is 38 percent Native American – the statewide average is 1.2 percent – and 25 percent black.

“It’s very disruptive and it’s very dangerous,” said Faircloth, a member of an indigenous community in Scotland and Robeson counties. The Chmura economic report showed that only 18 permanent jobs would be created in North Carolina, she added.

In some places, she said, the proposed pipeline would pass just several hundred feet from houses and trailers, raising concerns about safety if there was a fire or an explosion.

Few residents she has encountered outright favor the pipeline.

“Some of them are neutral and they’ll say things on the line of, ‘I don’t really want it, but what choice do I have?’,” Faircloth said.

Pipeline crews require a 110-foot-wide strip of land to work during construction, according to Dominion. The permanent right of way would be reduced to 50 feet. Landowners retain ownership, but are barred from planting trees or building on top of the right of way.

Of the 1,000 or so properties the pipeline would cross in North Carolina, about half have already signed agreements with the utility company, said Dominion NC spokesperson Aaron Ruby.

But Ruby said “it’s way too premature” for eminent domain – a law that allows property to be taken, with compensation, for public projects – to be an issue. The authority does not even exist, he said, until a project has received full federal approval.

The pipeline will allow large quantities of natural gas to be transported long distances to be distributed by local gas utilities to customers, Ruby said. It is not intended, he added, to be available for local communities or individual homeowners to tap directly.

Ruby said that buried pipelines are “by far” the safest way to transport natural gas, compared with rail and truck.

Many steps are taken to ensure the safety of the pipeline, during and after construction, he said. The pipeline itself is built with ½-inch to ¾-inch thick steel pipe, and the pipe is coated with epoxy to protect against corrosion. Before the pipeline is put into service, welds are X-rayed, and the lines are pressure-tested. Afterward, it is continuously monitored in real-time with sensors located inside the pipe. Any problems can be isolated to the individual pipe section and remote-controlled shut-off valves allow immediate response – an ability lacking in older systems.

There is also a robotic device called a “smart pig” that uses ultrasound technology to inspect the entire length of the pipeline every seven years.

More than 6,000 miles of potential routes were evaluated, with at least 300 adjustments made, before the proposed route was selected, he said. Demographics and socioeconomics of a community had nothing to do with the route selection, he said.

Ruby said that the lack of natural gas infrastructure is a prime reason that the region has struggled economically.

“That’s why this project,” he said, “is so critically important to Eastern North Carolina.”