BEAUFORT — Those who travel up and down North Carolina’s Outer Banks and through the Down East communities of Carteret County can see it’s an area of beautiful natural scenery, but during the next few weeks, new signs will be posted along the route to help travelers better understand the history and maritime culture of the region.

The corridor, which spans three counties and 21 communities and includes 138 driving miles and 25 ferry miles, was nationally designated as the Outer Banks Scenic Byway on Oct. 16, 2009. Special signs will soon mark the entrances to the byway, showing the way and directing travelers to byway attractions. The signs are being installed beginning this week along the route.

Sponsor Spotlight

“Basically, when all the signs go up the byway will be essentially built; it will be the birth of the byway in the public’s imagination,” said planning consultant Breann Bye of Des Moines, Iowa.

Speaking Thursday during a lunch meeting at the Beaufort Train Depot to explain the byway to those involved in tourism, museums and cultural and historical attractions in the area, Bye said about 130 signs will be erected along the route, with Memorial Day the target date for all to be in place.

“There’s no more exciting time for a byway than when the signs go up,” Bye said.

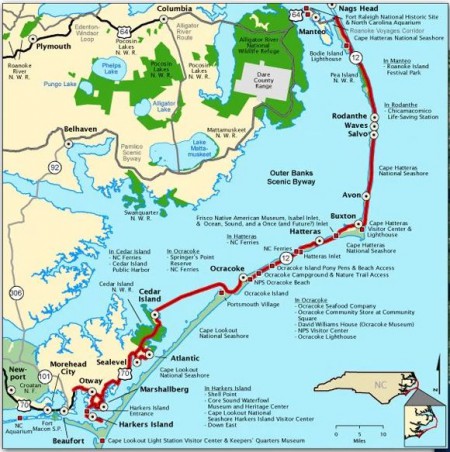

The byway begins at the intersection of N.C. 12 and U.S. 64 at the northern end of the Outer Banks in Dare County, continues along N.C. 12 south to Ocracoke in Hyde County and ends at the Merrimon Road-U.S. 70 intersection in Carteret County. Total drive time is about five and a half hours, including about 3.5 hours on two state ferries, but travelers are advised to set aside a few days for the trip in order to have the best experience.

America’s Byway Collection

North Carolina has 54 state byways and three other national byways: the 469-mile Blue Ridge Parkway, which is designated as an All-American Road; the Cherohala Skyway, a 43-mile National Forest Scenic Byway connecting Robbinsville and Tellico Plains, Tenn.; and the Forest Heritage National Scenic Byway, a 76.7-mile stretch through the Pisgah National Forest.

Sponsor Spotlight

Congress authorized the National Scenic Byway Program in 1991 and established it the following year. It includes 99 National Scenic Byways and 27 All-American Roads that encompass 155 individual state segments. The collection totals nearly 24,000 miles of roads in 44 states and 12 tribal lands, with 126 routes ranging in length from less than 10 to more than 1,000 miles.

The Outer Banks Scenic Byway is “geographically distinctive” in America’s byways collection, Bye said.

It traverses “one of the nation’s great coastal landscapes,” according to an Outer Banks Heritage Trails brochure provided at the meeting. The communities are “inhabited by people who have lived and worked here for centuries.”

Historic traditions such as boatbuilding and fishing, landmarks including four lighthouses, numerous museums and monuments and countless natural features that include unspoiled beaches, marshes and wildlife-viewing areas dot the map along the way. The route connects 15 N.C. Civil War Trail markers, the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, the Cape Hatteras National Seashore and departure points for excursions to the Cape Lookout National Seashore and other destinations accessible only by water.

Byway signs are to be paired with existing route signs to reassure travelers they’re on the right path. Markers will include directional signs to byway attractions, about 30 along the route in addition to other resources, and “orientation panels” at various locations such as ferry terminals that are to be coordinated with an interpreter project that includes the Heritage Trails brochure. The brochure lists locations where local seafood is available, dates of seafood-related events and a narrative on how byway communities were built on commercial fishing.

A byway is a way to communicate the intrinsic qualities of the area, Bye said.

“We want to connect with travelers in a way that’s very personal and answer their questions,” she said. “It’s about collaboration, communities coming together to decide what stories they want to tell.”

‘Sometimes Less is More’

Karen Amspacher, director of the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island, knows all about telling the region’s history. She said the cultural landscape of the area was the basis for the national designation. Lodging, restaurants and retail are more widely available along the northern Outer Banks but the Down East portion, her community, offers something different.

“Sometimes less is more,” Amspacher said, referring to the limited number of accommodations and lack of stereotypical tourist traps Down East. “We don’t need a Holiday Inn, we don’t need a golf course and we don’t need Putt-Putt. We just need a few folks coming through looking for our kind of place.”

She said the byway is an opportunity to showcase a way of life that doesn’t exist anywhere else. It’s scenic, but the area offers more for those interested in history and culture.

“It’s not just a place to go and look and see, it’s a place to go listen and learn and understand, we hope,” Amspacher said.

In addition to brochures and other printed materials, a byway website allows information to be regularly updated. The printed materials list nonprofit groups and state and federal agencies involved, but the website offers more flexibility and lists businesses, restaurants and seafood purveyors. Plans are in the works to expand the website’s search function.

“If you’re on the byway and interested in getting listed, let us know. It’s all a work in progress,” Amspacher said.

Connie Mason, a Carteret County historian, said the telling of the Outer Banks story must include “fun things,” such as Down East recipes, local legends and personalities, in order to have broad appeal.

“We’re trying to make it as interesting as possible, not just dry facts, and take it to the community and say, ‘what do you think about this?’” Mason said. “There are 13 villages Down East and seven at Hatteras and there’s so much material. The hard part is distilling it down and putting it in a form, into what the community wants to say about itself. There are plenty of images but we’re trying to find images that are unique to the area that might not be as well known, so they’ll be of interest.”

She said a priority was making each community along the route feel invested in the project and proud.

A Decade of Planning

The byway signs are the culmination of more than 10 years of work by community leaders in the three coastal counties.

Amspacher and Tom Steepy of Beaufort have been involved since the beginning, in 2005. That’s when Bob Vogel, then superintendent of the Cape Lookout National Seashore, proposed the idea. At the time, Steepy was on the Carteret County Board of Commissioners, and fellow commissioner Jonathan Robinson suggested him for the job.

Each of three counties appointed five to seven people to a byway committee to organize the effort and take on the big challenge of raising money.

“The committee was a revolving door for everyone but me and Karen, we’ve been there since day one,” Steepy said after the meeting.

Steepy said the first challenge was putting together a comprehensive management plan.

“That elevates you from a state level to the national level,” he said. “Once that plan was submitted to Washington and then it was recognized and awarded, three of us went to Washington to accept the recognition back in 2008.”

That recognition put the effort on par with the Blue Ridge Parkway, Steepy added. He said that recognition was long overdue.

“When I came here in 1990 I said, ‘What a fantastic place the Outer Banks is. How come nobody has ever organized and done something to emphasize and talk about this stretch of sand that’s one of the most interesting pieces in the entire world?’” Steepy said. “I think we are all pleased to see where we are now, and we can all see, having been through the process, how come it takes so long.”

To make the byway happen, the committee submitted applications for competitive grants at the federal level and state-level Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, grants. Then there was the challenge of finding money to meet the local matching requirements for the grants. In order to qualify for funding, the area had to offer at least two of six intrinsic qualities: archaeological, cultural, historical, natural, recreational and scenic.

“You could pick any five of the six but you only had to pick two and we picked history and culture, which are unique,” Steepy said. “A lot of the others across the U.S. are just recreational and sightseeing. We’ve got both of those but we also have the history and culture to go with it. It’s a very unique part of the world, really, and there’s a real story to be told. It may take a while but it’s taken years and years for the full development of the Blue Ridge Parkway and it’s the most visited byway in the United States.”

The total included more than $500,000 in federal grants and about $200,000 CAMA grants.

The two federal grants totaled about 250,000 for “way-showing,” or signage, and one for $265,000 for the interpretive phase — “So when you come into a village Down East, you can read something about the history and the culture and the people of that village,” Steepy said.

The N.C. Rural Center, an economic-development organization focused on rural parts of the state, provided money, as did area nonprofit organizations including the N.C. Coastal Federation. NC Catch, a partnership of local seafood advocacy groups, provided help with resource planning. Local electric co-ops, Cape Hatteras Electric Cooperative, Carteret-Craven Electric Cooperative and Tideland Electric Membership Cooperative, also chipped in to help cover website costs.

“And everything had to go through DOT,” Amspacher said.

The timing was also key. The Federal Highway Administration no longer funds the National Scenic Byways Program and no further designations are being considered.

The federal money for the Outer Banks Scenic Byway signs came in five years ago, Mason said, adding it had taken this long to find a sign maker to create them within the budget.

A gateway welcome center is planned for a Carteret County-owned site near East Carteret High School. The county is providing the property for parking and informational kiosks relevant to the byway and has agreed to maintain it. County Manager Russell Overman said the facility is to be ready by September 2017.

“The property is acquired and we’re working to make the improvements,” Overman said, adding that no restrooms will be included because access to Beaufort’s water and sewer had yet to be extended. “That’s in the plans but it will take additional money.”