SCOTTS HILL – The terminal groin proposed for the north end of Figure Eight Island is a catalyst for the debate on how far coastal communities should go to tackle beach erosion hot spots.

Are sea walls, sandbags and other engineered solutions, worth the government resources and expense of saving homes in erosion-prone coastal areas? What about the cost to wildlife that depend on the beach habitat?

Supporter Spotlight

The complexities of protecting coastal property and preserving public trust lands and coastal habitat intersected during a March 5 public forum about Rich Inlet, one of North Carolina’s few remaining natural inlets.

A final environmental impact statement on a proposal to build a terminal groin at Rich Inlet is expected to be released in late spring or early summer.

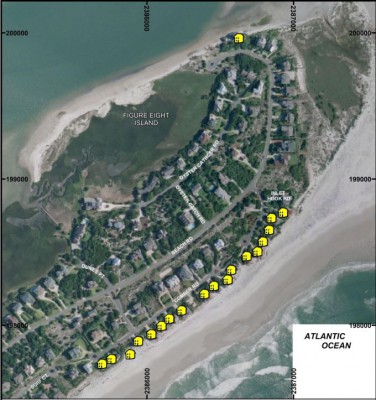

The Figure Eight Island Homeowners Association’s Board of Directors is pursuing the groin project. It argues that a hardened structure cutting across the island’s north end will stabilize the inlet and reduce what has, at least in the past, been severe erosion.

How to best protect beach communities from erosion is a widespread discussion among hundreds of beach towns across the country and the globe, said Rob Young, professor of coastal geology and director of the Program for Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University.

Young, a panelist, offered a broad, national perspective on hardening coastal shorelines.

Supporter Spotlight

“For those of you paying for the project, prepare to be surprised,” he said. “If you’re lucky it may be a good surprise and it may perform better than designed. Be honest about the degree of uncertainty.”

His prediction: if Figure Eight builds a terminal groin and the erosion pattern changes, “there will be a lawsuit.” He warned property owners to factor that into the cost of the project.

He referenced a case on Florida’s Atlantic shore where a town that built a terminal groin on Sebastian Inlet was sued for causing sand deprivation by another town about 30 miles south. The plaintiffs won.

A Stable Inlet

Environmental groups, including the N.C. Coastal Federation, refute both of the Army Corps of Engineers’ draft environmental studies on the proposed project.

Rich Inlet is one of the most stable natural inlets, and the sandy spit at the northern end of Figure Eight is growing, not eroding, environmentalists and some coastal geologists argue.

Building a terminal groin in the inlet would alter the inlet’s “flushing” ability during coastal storms, destroy habitat crucial to migrating and nesting coastal fowl and have unintended consequences, they say.

“It’s a natural inlet,” said Walker Golder, Audubon North Carolina’s deputy director. “It hasn’t been modified in a significant way and it has the habitat that birds need, that fish need, that lots of other wildlife along our coast need.”

Golder was among a handful of panelists at a “Save Rich Inlet” forum, where more than 100 people gathered at Poplar Grove Plantation near Wilmington to learn more about the proposed project and its potential impacts.

Audubon has been studying the inlet since 2010, recording 104 species of birds, including the critically endangered Great Lakes piping plover. Figure Eight Island is generally the southernmost nesting area for piping plover, Golder said.

The inlet is also a rest stop for migrating red knots, small birds that have one of the longest migrations – upwards of 18,000 miles round trip from the Arctic to South America and back.

“Can these birds simply go somewhere else? That’s a question that we get frequently. They’re already at the last best places that they depend on for survival. A matter of going somewhere else is no longer an option for a lot of species of birds that depend on these inlets,” Golder said.

If a terminal groin is built in Rich Inlet, dozens of acres of sandy habitat at the north end of Figure Eight would eventually erode away, which the preliminary environmental study confirms.

Southern Environmental Law Center attorney Geoff Gisler said the model over-predicts erosion. “Right now the shoreline is accreting and there is no immediate need to remove housing,” he said.

Bill Cleary, a retired geology professor and member of the N.C. Coastal Resources Commission’s Science Panel on Coastal Hazards, has been studying Rich Inlet for about four decades and defends the project, which is projected to cost an estimated $63 million.

The sandy spit, he said, is “incredibly dynamic.” Cleary, who attended Saturday’s forum, said he’s studied scores of photographs dating back to the 1930s through present day of the inlet. More than 70 percent of the time the spit is 25 percent of the width it is now, he said.

“The spit’s going to disappear anyway,” Cleary said. “The models in the EIS are not going to tell you exactly what’s going to happen but I think there’s enough information that you can get a pretty good idea of how the inlet’s going to change.”

A terminal groin would work well in protecting against beach erosion on the northern end, he said. When asked what potential implications a groin could have on the inlet, Cleary answered, “Nothing.”

“To me, I don’t see how it’s going to impact it,” he told panelists.

Another panelist, coastal and marine geologist Stan Riggs, disagrees with Cleary.

Riggs argues that one consequence of terminal groins is the accelerated erosion that occurs farther down the beach. The groin traps sand that would otherwise naturally build up those beaches. This is evidenced in areas where terminal groins have been built along the East Coast, said Riggs, who is also a member of the CRC’s science panel.

“It’s happened on every inlet, not just in North Carolina,” Riggs said. “You put that terminal groin in and the sediment that moves along the shore can’t get there. If you put that thing in there it changes all that equilibrium. The absence of that sand on Figure Eight is going to increase the potential recession.”

State lawmakers need to seriously begin to explore how much of the coast should be engineered, he said.

“Do we want natural beaches or do we want nothing but pumped beaches?” Riggs asked.

North Carolina lawmakers in 2011 ended the state’s longtime ban on hardened structures along oceanfront by passing a bill that allowed up to four terminal groin projects. The General Assembly has since expanded that to two additional projects.

Bald Head Island will be the first to complete a terminal groin since the law was changed. Ocean Isle Beach and Holden Beach in Brunswick County are in various stages of seeking permits to build terminal groins.

‘Not To Protect 10 Homes’

Erosion, Young said, is not usually an existential threat to an entire beach community or island.

Young asked the audience to think about alternatives to shoreline hardening, such as relocating structures rather than trying to hold erosion in place in front of “hot spots.”

“You have time on Figure Eight Island for that,” he said. “You don’t have homes that are about to dive into the ocean.”

Figure Eight Island HOA Chair Frank Gorham said the association’s board of directors is “not doing this to protect 10 homes. We’re doing this to stabilize our island.”

Mother nature is moving Rich Inlet south, he said. Gorham, who is also chair of the CRC, said that the southern migration of the inlet will eventually erode the sand spit and destroy homes. Stabilizing the inlet with a terminal groin will considerably reduce the amount of dredging in the inlet channel, he said.

“Terminal groins” are rock or sheet metal walls built perpendicular to the shoreline. They are similar to jetties, but smaller. They are designed to lessen erosion, not prevent the migration of a channel. For that, much larger jetties are built.

Gorham criticized the forum for lacking balance, saying that the audience heard a one-sided story.

Mike Giles, a coastal advocate with the federation, said he contacted Figure Eight Island Administrator David Kellam in December and invited the HOA’s board of directors and their consultant to participate in the forum.

The HOA board must obtain property easements before construction of a groin may begin. Gorham said the board will start seeking those easements after the release of the final environmental impact statement.