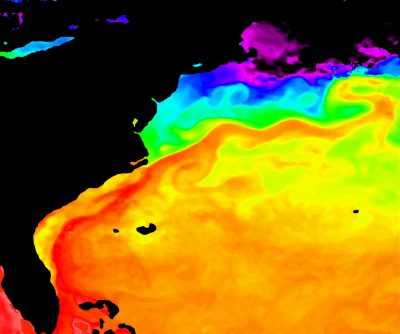

MANTEO — The Gulf Stream passes at times just 12 miles from Cape Hatteras. The amount of water it carries past our coast is massive. In fact, if it were a river, the Gulf Stream would be the greatest river that ever existed on this planet.

“By the time the Gulf Stream gets off Cape Hatteras (it’s greater than) the flow of all the rivers of Earth . . . 45 times greater the entire flow of every river on Earth is what we have off Cape Hatteras,” said Mike Muglia of the Coastal Studies Institute on Roanoke Island.

Supporter Spotlight

A team of researchers and scientists from the institute, N.C. State University and the Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City has been studying for the last two years whether all that water could be put to use to create electricity.

“Is there a resource there and is it enormous? Absolutely,” Muglia said, then asks the important question. “Is it a viable resource?”

It is still too early to tell, but there are characteristics of the Gulf Stream as it passes the Outer Banks that may make better suited for energy production. As it flows north past the Outer Banks, the Gulf Stream is constrained from changing position by the edge of the continental shelf on its west side, Muglia explained. It veers east into deeper water at The Point, an undersea geologic structure about 40 miles off Hatteras Island, and its course can meander.

“The key point is that off of Hatteras, the variability in available energy at a specific location is due primarily to the variability in the Gulf Stream location,” he said.

The Gulf Stream gains three times the amount of flow as it moves north up the Southeast coast. Its flow is measured in svedrups, or Sv — named for the late Harald Sverdrup, a pioneering oceanographer and an early director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California. Off the south Florida coast, the stream’s flow is 33 Sv, or 33 million cubic meters per second; by the time the current reaches Cape Hatteras it’s flow has increased to 90 Sv.

Supporter Spotlight

However, with no banks to constrain its flow, the location of the Gulf Stream is not a constant, nor is the force of the current the same at all times. Because it varies in place and flow as much as it does, if the Gulf Stream is to be developed as an energy resource accurate predictions of its fluctuations will be needed, the researchers noted.

Ruoying He, an oceanographer at N.C. State, develops models of coastal circulation currents. It is the modeling that his group has created that is being used to predict where the Gulf Stream will be and the force of the current as it moves past the Outer Banks.

“I got involved in this project because my team at NC State develops a high resolution computer model to predict ocean circulation off the East Coast of U.S.,” He wrote in an email in response to a question. “Similar to the weather forecast, our model provides time and space continuous ocean state . . . predictions. They are quite useful to fill observational gaps and help understand Gulf Stream variability measured by (the) limited suite of observational assets we deployed . . .”

The models He’s team have developed have been remarkably accurate, according to Muglia. “We’ve compared (our) measurements to the model and the model does an extremely good job of capturing the average speed over a long time period,” he said.

He notes there is more work to be done. The model has done a good job of predicting the amount of flow in the Gulf Stream and giving a good idea how it fluctuates. However, if the resource is going to be developed, better information is needed.

“A major research area in my team is to further improve the accuracy of our ocean prediction model,” He wrote. “The model is doing a decent job in predicting the Gulf Stream variability. We hope, through further model refinements and data assimilation, we can perform accurate real-time . . . forecasts of the Gulf Stream to support (and) optimize offshore surveys and energy harvesting efforts.”

Researchers in Florida are also studying how to harness the power of the Gulf Stream to produce electricity.

Whether the Gulf Stream can be utilized as an energy resource is still very much up in the air. Muglia notes there are a number of hurdles that must be crossed before energy will surge from the waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

“Is it a viable resource in terms of permitting? Is it a viable resource in terms of economics? Engineering?” he asked.

Those questions, especially the topic of engineering, are being addressed by John Bane at the Institute of Marine Sciences. He points out that the studies that are being done are comparable to almost any study looking at a potential energy resource. “The observations that Mike has made shows very clearly that it (the Gulf Stream) fluctuates. It’s very similar to studies of wind energy,” he said.

Expanding on that, Bane talked about other energy resources. “If you were out in West Texas and wanted to drill for oil, you would examine and explore where oil might most likely be. This is a resource assessment. That’s what we’re doing.”

The assessments are ongoing and expanding. Initially the instruments used to measure what was happening with the currents were coastal radars, ongoing measurements taken from instrument in the sea and onsite observations. Instrumentation is being increased to look at a broader cross section of the Gulf Stream, giving the scientists a better picture of the energy closer to shore where it may be more accessible and farther out to sea where there may be more potential energy but the cost of engineering would become higher.

The first biological assessments are also being done. The role of the bottom arrays that are used to assess current and flow is being expanded.

“These now have hydrophones on them. We’re passively listening and seeing what kind of critters we have out there,” Muglia said. “We’ve certainly observed clicks and marine animals. Some of them seem pretty curious. We have one where it sounds like he comes right up to the instrument.”

A place of verdant sea life, the Gulf Stream has been a remarkable asset for the Outer Banks for as long as the islands have been populated. Whether it will be a part of the energy assets of North Carolina is still an unanswered question.

“We really are just trying to understand what the resource is and whether it’s a viable resource,” Muglia said.