WILMINGTON – Residents and activists urged regulatory agencies at a public hearing on Figure Eight Island’s proposed terminal groin to reject the project, saying it will ruin one of the most stable natural inlets along North Carolina’s coast.

One by one, about 20 residents of New Hanover and Pender counties at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ public hearing Sept. 2 said they oppose the project the private island’s homeowners association’s board of directors says is needed to protect the north end from eroding. Dozens more in a crowd of roughly 100 people gathered in an auditorium at an elementary school off Middle Sound Loop Road applauded in support of those who spoke.

Supporter Spotlight

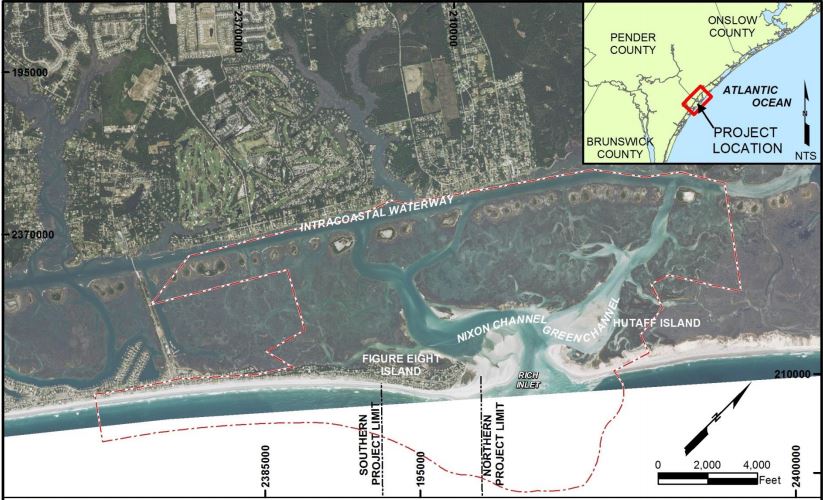

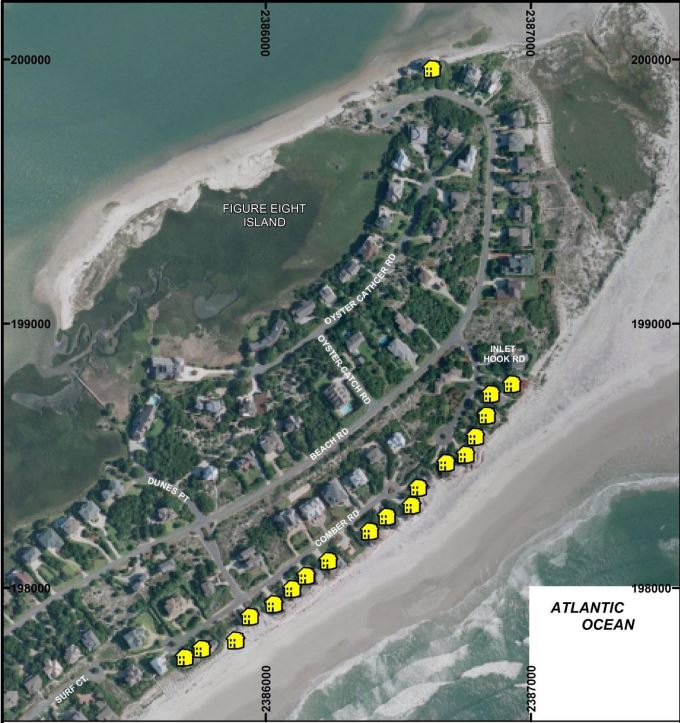

The proposed 1,500-foot-long structure would be built along the southern shoulder of Rich Inlet. The 30-year project would also include supplemental beach renourishment on about 4,500 feet of oceanfront beach and 1,400 feet of sound shoreline on the island.

The terminal groin would be built landward of a sprawling sand spit that has built up over the years on the island’s northern end from the natural migration of Rich Inlet.

This area is habitat to dozens of shorebird species, including the federally endangered piping plover and red knot.

A terminal groin would permanently remove the spit those birds depend on for nesting, foraging and resting, opponents of the project say.

“It’s not just any inlet,” said Middle Sound resident Mike Wilson. “The unspoiled inlet and intertidal areas are so important. The costs, and I’m not talking about financially, far outweigh the benefits.”

Supporter Spotlight

Priss Endo, another Middle Sound resident, said a terminal groin would result in the loss of the natural inlet, habitat, public waters and pristine beauty.

“God forbid that any of the plans in the EIS be adopted,” she said.

The Corps released its supplemental draft environmental impact statement, or EIS, in July. The document is an update to the Corps’ 2012 draft study and includes the newest terminal groin design and location preferred by the island’s HOA board of directors.

The proposed location of the terminal groin is about 420 feet north of the preferred site in the original draft study, a change made at the request of property owners at the northern end of the island.

Several of those property owners will have to grant the HOA easements to their properties in order for the project to be built across their land.

Mickey Sugg, project engineer with the Corps’ Wilmington office, said the HOA board can get a permit from the Corps prior to obtaining any easements.

Those easements must be obtained before the board can submit an application to the N.C. Division of Coastal Management, according to the rules adopted by the state Coastal Resources Commission, said Mike Giles, coastal advocate with the N.C. Coastal Federation.

Unsupported Claims

Giles and others at the hearing said the supplemental EIS is flawed because the document does not use current shoreline conditions needed to study how the roughly 65 acres of sand at the northern end of Figure Eight Island would be affected by a terminal groin.

“The computer model results in the document do not support claims made that a terminal groin results in beach profiles that are most protective of private property,” Giles said.

Tom Jarrett, a consultant with Coastal Planning & Engineering, the firm the HOA board hired to do the project application, used charts and aerial photographs to show the inlet’s history of wagging back and forth, a process that builds up the northern end of the island, then erodes the sand away.

Jarrett said the channel is starting to move back toward the north.

“It could start a new erosion episode on the north end,” he said.

Building a terminal groin would be like taking out an insurance policy on the island’s north end, he said. Should erosion begin to occur if the channel continues to move north, the terminal groin would be there to protect properties.

The tradeoff of guarding those homes over potential adverse effects to the inlet and the crucial habitat it provides is too great, opponents of the proposed project say.

Matthew McIver, an aquatic scientist at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, said that scientific studies of hardened structures in inlets are evidence that a terminal groin would destroy the natural state of Rich Inlet.

Such an event would deprive shorebirds, including federally endangered and threatened species, of habitat they depend upon for survival, said Walker Golder, Audubon North Carolina’s deputy director.

Rich Inlet serves up to 20 percent of the critically endangered Great Lakes piping plover population, he said.

Golder said the EIS fails to consider the cumulative impacts a terminal groin would have on the inlet and the habitat it provides.

“The Endangered Species Act should be enough to stop this,” said resident Charles Robbins.

Environmental groups have been critical of the Corps’ EIS process, saying the agency has not followed the National Environmental Policy Act by holding formal consultation with federal fish and wildlife agencies.

The Corps has been discussing the proposed project with those agencies, including the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, according to Sugg.

He said he is currently reviewing the draft biological assessment, which will at some point be turned over to wildlife agencies.

It is unclear when a final EIS will be released.

The Corps will continue to take public comments on the proposed project through Sept. 14.