Part of a series about the effects federal budget and staff cuts and the cancellations of programs and services are having in coastal North Carolina.

MANTEO — In the six months since the chaotic and seemingly random cutting in the federal government began, a terrible uneasiness has descended on the northeast corner of North Carolina, where all of the state’s nine national wildlife refuges employ neighbors and family members who live in the rural communities in which they’re located.

Supporter Spotlight

At least 10 Coastal North Carolina National Wildlife Refuge Complex staff and five employees of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s regional Ecological Services office in Raleigh, so far, are believed to have voluntarily left their jobs, whether nudged by coercion or incentives.

With staff forbidden to speak with media, and ongoing legal challenges and limited public information creating uncertainty, no one appears to know what will happen to their refuges.

“I just found out we should be getting some staffing numbers from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the next couple of weeks,” Howard Phillips, the Southeastern representative for the National Wildlife Refuge Association, a nonprofit advocacy and support group for the refuges, told Coastal Review, citing informed but unofficial sources. “The dust seems to be settling a little and (the agency) is starting to get a handle on where they stand.”

But Phillips, who retired at the end of 2020 as manager of Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge in Tyrrell County, says he fears that serious consequences are already baked into the refuges’ cake, no matter what the government decides to do. The lack of trust engendered by often abrupt, unexplained cuts of staff, research and budgets as well as the “crippling” brain drain of expertise, experience and local knowledge has only made the situation more problematic.

“Could the administration suddenly decide they want to hire everybody back and start doing conservation again?” he continued. “That would take at least six months, probably 12 months. They’d have to be trained.”

Supporter Spotlight

The stark reality, he added, is that without knowing the Trump administration’s timeline or goal in the current upheaval, it’s impossible to understand the long-term impacts and impractical to expect much to change, much less improve.

“I mean, they’ve just given no indication that they’re going to do anything that’s going to reverse the trend right now, which is down, down, down, down,” Phillips said.

An unnamed spokesperson from the agency’s public affairs office ignored Coastal Review’s request to authorize or facilitate a refuge staff interview, but responded to several questions about impacts on North Carolina’s wildlife refuges in a May 23 email.

“As part of the broader efforts led by the Department of the Interior under President Trump’s leadership, we are implementing necessary reforms to ensure fiscal responsibility, operational efficiency, and government accountability,” the spokesperson wrote. “While we do not comment on personnel matters, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service remains committed to fulfilling our mission of conserving fish, wildlife, and natural resources for the American people.”

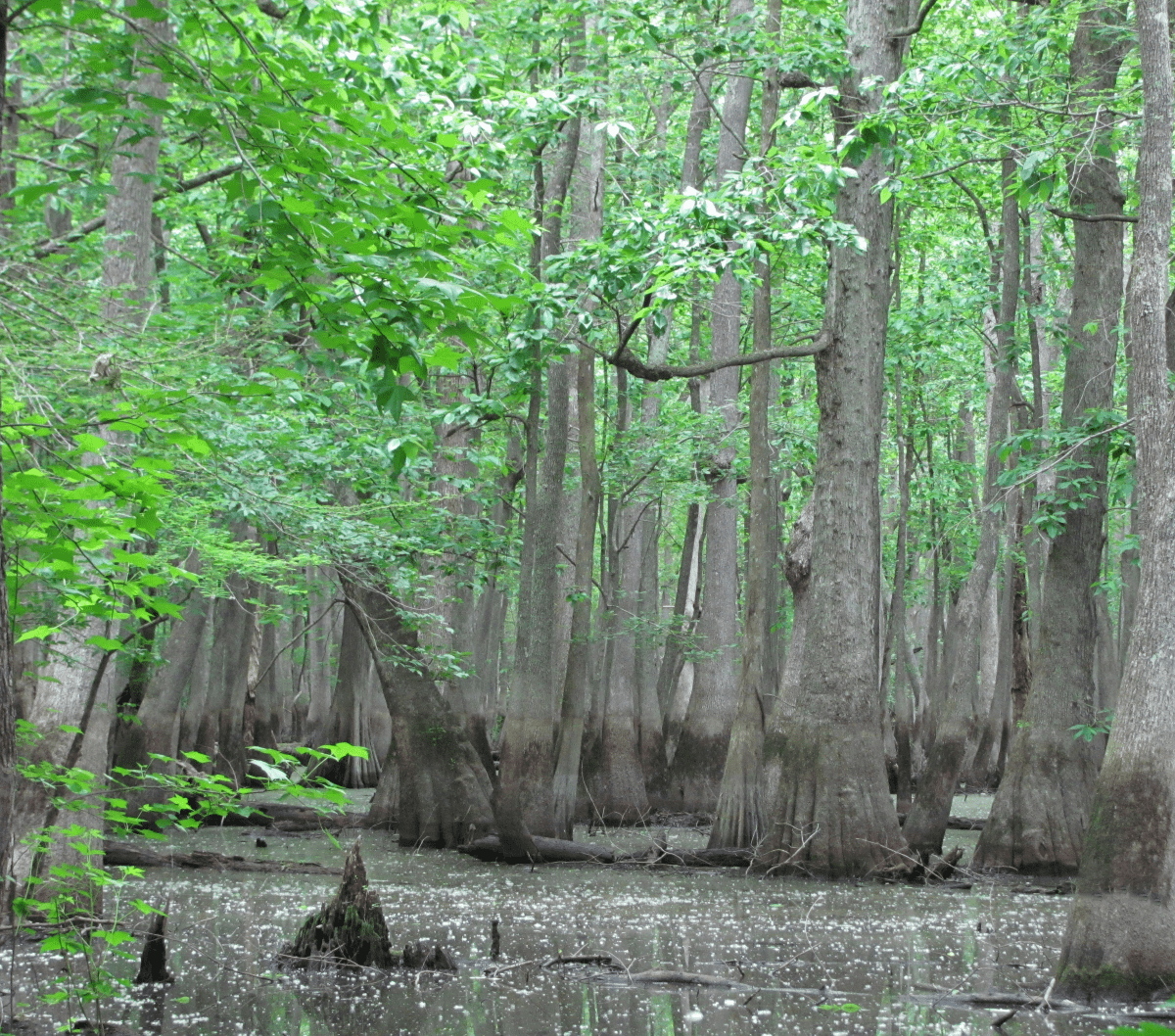

Refuges in the coastal complex encompass nearly a half-million acres of farmlands, swamp forests and pocosin peatlands, intersected by rivers, streams, canals, lakes and sounds within the nation’s second-largest estuarine system.

The nine refuges — Alligator River, Pea Island, Mackay Island, Currituck, Mattamuskeet, Pocosin Lakes, Cedar Island, Swan Quarter, Roanoke River — are stretched along vast swaths of geography in the coastal plain that provide habitat for unique species and globally important ecosystems.

For instance, the critically endangered wild red wolves, the only surviving in the world, roam within a five-county recovery area based out of Alligator River, descendants of Spanish mustangs range free in Currituck, and thousands of migratory birds and waterfowl passing along the Atlantic Flyway overwinter every year at Mattamuskeet and Pocosin Lakes.

Mattamuskeet, the state’s largest natural lake, is undergoing an innovative and intensive watershed restoration project many years in the planning. And Pocosin Lakes, named for the Native American term for “swamp on hill” because of its boggy peat soil, has been studied by Duke University researchers for its ability to remediate carbon pollution. The refuge has also nearly completed an extensive rewetting project to restore the ability of the pocosin peat to absorb carbon dioxide and resist wildfires.

Two major wildfires in and around the refuge in recent decades have burned deep in the ground for many weeks, spewing tons of carbon back into the environment, with one smoldering for six months before it was finally extinguished.

Therein lies the dilemma — and the risk — to the refuges: What happens when there’s no one available to take proper care of the refuges, and to even continue the conservation mission?

Pocosin Lakes, for instance, with the recent retirement of former manager Wendy Stanton, no longer has a refuge manager.

“You know, with Wendy gone now, I don’t know that there’s anybody left at Pocosin Lakes that really understands that hydrology restoration and how it works,” Phillips said.

But it’s more than the upper-level staff, said Bonnie Strawser, president of the Coastal Wildlife Refuge Society, a local nonprofit group that supports all of the eastern North Carolina refuges. It’s also the loss of staff that maintain buildings and trails, she said, as well as the biologists who monitor water and test soil.

Strawser, who retired in 2020 after 40 years with Fish and Wildlife as visitor services manager, said that the project leader for Coastal North Carolina National Wildlife Refuge Rebekah Martin has designated acting managers in each refuge, but that’s in addition to their regular jobs with the refuges.

Martin is based at the agency’s Roanoke Island headquarters but is not authorized to speak to reporters. According to a 2023 article on the coastal refuges website, Martin oversees about 400,000 acres of habitat with more than a dozen endangered or threatened species. At the time, it said, the complex had 35 employees and more than 400 volunteers.

“We are currently down to 10 staff, and this is regular O and M — operations and maintenance — funded by general funding, refuge funding,” Strawser said in a recent interview. “Now that does not include firefighters or law enforcement, because they are funded through different programs.”

Strawser said that there were no probationary employees in eastern North Carolina, so no one had been outright fired. Some staff who agreed to resign under one of the agency’s two rounds of the deferred resignation program, she said, were quickly shut down and put on administrative leave for varied periods of time while collecting their salaries.

Cuts in both the U.S. Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service will also hamper the agencies cooperative response to wildfires and disasters, including with the national interagency incident management teams. Strawser is a member of one of three teams in the southern area.

“I don’t know what in the world we’re going to do when fire season comes,” she said. “They stood down our team. It’s not going to be available, they said, at least until after July.”

As Strawser noted, a lot goes on behind the scenes to keep the refuges humming, including procedural processes to keep records and run programs, as well as have sponsors to maintain the “casual hire” personnel to respond to emergencies.

“But the Fish and Wildlife Service, because they lost so many people in the administrative positions, they don’t have anybody to handle the payments and the travel, so they can’t sponsor” for a team member, she said.

For the time being, the public many not notice much difference when they go to a refuge, Strawser said.

“The visitor centers are run by volunteers,” she said. “The public programs are conducted mostly by volunteers.” But there’s only three maintenance people for their nine national wildlife refuges.

“There’s been no talk of closing anything, but it’s just common sense there will problems if there’s nobody to grade the roads, if there’s nobody to do the mowing on the road shoulders, she said. “And if there’s no ‘daylighting’ of the roads, they’ll get overgrown, the sun won’t reach down, and the mud doesn’t dry out and the road is destabilized and before you know it, they’re not drivable.”

Mike Bryant, who was succeeded by Martin, had served as refuge manager for 20 years, from 1996 to 2016, and he witnessed decreasing support for the refuges from the federal government, he told Coastal Review in an interview. After retirement, he had also served as consultant for the National Wildlife Refuge Association, and was former president of the Coastal Wildlife Refuge Society. Although he said he keeps in touch, he is no longer directly involved with either group.

Since about 2010, Bryant said there has been a steady decline in staffing.

“You have refuges where there were multiple people, and with some of them, there’s just one person left, and so that’s part of the story,” he said. “So it had nothing to do with the past 60 or 90 days, whatever it is now.”

But it’s not just mandated reductions in staff that threaten the refuges, he said. The management challenge is also an aging workforce that may not be replaced.

“You got over half a million acres of National Wildlife Refuge in multiple counties, and spanning across North Carolina to the Virginia border, with all kinds of infrastructure and management mandates and no staff to get those mandates done,” Bryant said. “They’re just wondering, how are we going to meet our responsibilities if we’re the only ones left? It’s a morale buster.”

After being fully staffed around 2003, he said it seemed as if the Department of Interior stopped prioritizing conservation and Congress slowly began losing interest in supporting the refuges.

“The Fish and Wildlife budget has so many facets to it, so many other responsibilities under various laws, endangered species and ecological services and all these other entities within the agency, fisheries and all those things, are all important,” Bryant said. “But Congress was never convinced to budget specifically for operations and maintenance of national wildlife refuges.”

Meanwhile, scores of new refuges came on line in the last 25 years. And rather than hiring more personnel, more work was heaped on less staff.

“I was hired in 1996 to manage Alligator River and Pea Island,” Bryant said. “Two years later, when the manager left Mackey Island and Currituck refuges, the regional office called me and said, ‘Hey, we want you to manage those two.’ All of a sudden, I had four refuges.”

Two years later, he was told to hire and supervise a new manager at Pocosin Lakes. Then staff was reduced, forcing him to share staff between the refuges. Next, Roanoke River was added to his responsibilities — along with the 90-minute drive each way. During all those years, he was bumped up just one pay grade.

Bryant said he gets why people get frustrated with the inefficient, cumbersome aspects of the federal government. But he remembers back when the Clinton administration had reduced both staffing and regulations, and not only succeeded, but ended up with a balanced budget.

“We went through all of those things without ever feeling like the sky is falling,” he said. Rather than taking rational steps to achieve efficiency, the interest now seems more in “just destroying the government, constantly degrading it, and yes, crafting corruption.”

“There’s a few bad actors, no doubt, always, in every organization everywhere, no matter what the enterprise,” Bryant added. “There was a rational process to deal with bad employees, grounded in policy. And the policy was grounded in regulation, and the regulation was grounded in law.”

The first official unit of the National Wildlife Refuge System was Pelican Island in Florida, established for conservation in 1903 by President Theodore Roosevelt. Today there are 570 refuges and 30 wetland management districts on more than 150 million acres entrusted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services and enjoyed by 69 million visitors.

Bryant is rooting for not just survival of the struggling refuge system, but its revival.

“I think we’ll recover,” he said. “I’m optimistic about that. But we’ll be deeply scarred.”