Editor’s note: Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the state’s coast. More of his work can be found on his personal website.

Today I am remembering a trip last fall, when my wife traveled to a conference in Cape Neddick, Maine, and I went with her. It was a lovely area — the wild and rocky seacoast, the salt marshes, the bogs, all of it.

Supporter Spotlight

While we were there, we took a few extra days to explore that southern part of the Maine coast. We drove up to the old Shaker settlement in Alfred. We visited Winslow Homer’s studio at Prout’s Neck. We went bird watching at Biddeford Pool. We hiked in the Kennebunk Barrens.

One drizzly day though, while Laura was at her conference, I drove down to the Portsmouth Atheneum, a venerable old library located in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 15 miles south of Cape Neddick.

Located on the Piscataqua River, which is the dividing line between Maine and New Hampshire, Portsmouth was one of New England’s most important seaports in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Founded in 1817, the Portsmouth Athenaeum is above all a library of America’s maritime history. Its books, manuscripts, maps, art, and relics speak to the distinctive maritime heritage of Portsmouth and of the Piscataqua’s lesser seaports, shipyards, and fishing villages.

But the Athenaeum’s collections were not only of local interest. Shipping and shipbuilding tied the region’s seaports to the whole North Atlantic. In the library’s collections, you can learn about the places where local merchant vessels did business, and sometimes where they came for refuge or even to their end.

Supporter Spotlight

One of those places, as we’ll see, was the North Carolina coast.

My special interest — aside from the popover shop across the street from the Athenaeum (worth the trip) — was a collection of historical manuscripts in the library’s collection that date to the early 1800s.

They are the records of the New Hampshire Fire and Marine Insurance Co., a firm that was based in Portsmouth and specialized in insuring local merchant sailing vessels and their cargos.

The company was in business from 1802 to 1822. During that time, it occupied the handsome, three-story brick building in Market Square that is now the home of the Portsmouth Athenaeum.

When the insurance firm closed in 1822, the board of directors passed the building onto the Athenaeum. Evidently, when they moved in, the library’s caretakers discovered the company’s business records had been left in the building’s vault. They became the first, or one of the first, groups of historical manuscripts in the library’s collection.

For me, as a historian of the North Carolina coast, the most compelling manuscripts in the insurance company’s records were the claims reports of shipwrecks and storm damage that had some connection to the Outer Banks and other parts of the North Carolina coast.

Only half a dozen of the company’s claims reports involved the North Carolina coast. Nevertheless, I found them a riveting look at seagoing life in that day and time, and most definitely worth the trip from Cape Neddick.

(Again, I would have made the trip for the popovers, so the manuscripts were gravy.)

I found the sworn affidavits in the claims reports the most exhilarating. Most were firsthand recollections of mariners who had lived through a storm or a wreck that had led to an insurance claim.

When I read those affidavits, I felt as if I could almost hear the voices of those seamen as they struggled through storms that came perilously close to sending them to the bottom of the sea.

-2-

Some of the oldest insurance claims that I found related to the North Carolina coast, I mean, were those of the brig, Alligator. According to the claims report, she limped battered and beaten up the Cape Fear River and anchored off Wilmington, on the first day of February 1805.

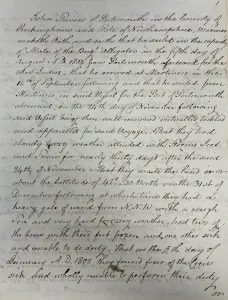

The insurance company’s policy on the Alligator was a bit of a dry read, but I found far more drama in the testimony of John Stavers, one of the mariners who served on the Alligator.

According to Stavers’ testimony, given before a notary in Wilmington, the Alligator had sailed from Portsmouth to Martinique, which at that time was a French colony where most of the inhabitants were enslaved African laborers imprisoned on sugar plantations.

On Nov. 24, 1804, the Alligator left Martinique, bound for Portsmouth, with a hold full of the ill-gotten molasses and sugar.

She quickly ran into foul weather. In his account of the Alligator’s misfortunes, Stavers testified, “That they had very cloudy hazy weather attended with storms, ice and snow for nearly 30 days….”

The Alligator finally made land on Dec. 1, but a heavy gale out of the north-northwest brought in “a rough sea and very hard freezing weather” that pushed them back out to sea.

Stavers testified that two of his fellow sailors had “their feet frozen.” Another of his mates fell sick, leaving the Alligator shorthanded in the storm.

On Jan. 5, things got worse. Stavers recalled that four more crewmen fell sick and were incapacitated.

Soon the storm also began to take a toll on the Alligator. He and his shipmates were hit, Stavers said, with “severe freezing weather and strong gales of wind from W.N.W.”

The heavy seas sprung the brig’s mainmast.

Then, he told the notary, “the bulk-head labored, and the water ways complaining and one of the Plank shares washed off, and the sails and rigging [were] much cut with the ice—some of the chain bolts carried away, and one of the topmast back stays, [so] they tore away before the wind for the Port of Wilmington N.C.”

He testified that they did so for “the preservation of their lives.” According to Stavers, the brig’s master did not believe that they could make any other port before the Alligator fell to pieces.

Stavers ended his report by telling the notary that they had barely made it to the mouth of the Cape Fear River.

“They had heavy gales of wind with snow and ice with a rough sea,” he swore.

The Alligator struggled to make it through the storm, taking in a great deal of water, until finally, on Feb. 1, 1805, “they came to anchor up the River near Wilmington.”

-3-

Many of the claims reports also featured the sworn testimony of local port officials and shipyard workers.

That testimony focused on their evaluations of the extent of a vessel’s damage, the necessity of repair, the costs of the repairs and what shipyards and maritime tradesmen did the work.

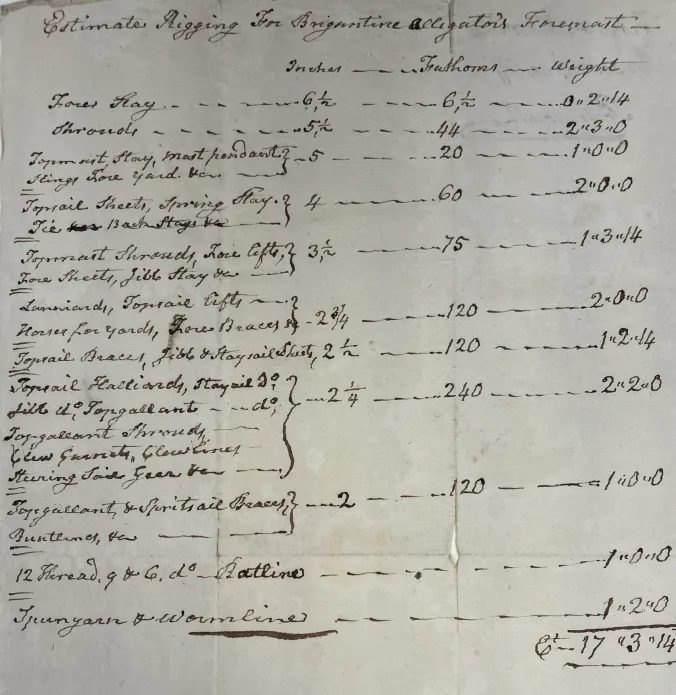

With respect to the Alligator, for instance, the claims report includes the port wardens’ assessment of the damage that the brig had suffered and of the extent of the repairs that had been done in a Wilmington shipyard.

The report also provided a rundown of the tradesmen who worked on the Alligator and a list of the ship chandlers who supplied the materials for the repairs.

The list of the shipyard workers included those I rarely see in seaport records. In this case, the appraisals, receipts, and job orders listed two ship’s carpenters, William Thidden and Thomas Hunter; a sailmaker, Bethel Gentry; a blacksmith named London Harris; and a block maker named either William Bells or William Bills. (The name was hard to read.)

They also indicated that John Woods led the repairs of the Alligator’s rigging, while John Lord supplied planking for the repairs and a merchant named Richard Langdon supplied naval stores.

There was also a rather general bill from a ship chandler, David Smith. He evidently supplied cordage, rudder iron, new spars, and even 13 barrels of flour and 2 boxes of fish that were apparently crew rations either for the voyage home or for the period while they were waylaid in Wilmington.

-4-

Around the same time, another vessel insured by the New Hampshire Fire and Marine Insurance Co., the brig Rockingham, grounded at Currituck Inlet, on the northern end of the Outer Banks.

In the claims files for the incident, I read that the Rockingham’s master, Nathaniel F. Adams, gave sworn testimony that he and his crew had sailed from the British colony of Grenada, in the Windward Islands, bound for Norfolk, Virginia, on Christmas Eve 1803.

Capt. Adams did not indicate the Rockingham’s cargo, but Grenada was another notorious slave labor colony and had recently repressed yet another slave rebellion.

Over a period of 125 years, the British, and the French before them, had shipped an estimated 125,000 Africans to Grenada to serve as their workforce there.

By 1803, when the Rockingham was there, the vast majority of the island’s slaves were confined on sugarcane, coffee, and tobacco plantations. When the brig sailed for Norfolk, its hold was likely full of the products that they had been forced to produce, most likely sugar, rum, and/or molasses.

According to Capt. Adam’s testimony, the Rockingham had a “pleasant breeze” and smooth sailing for the first few weeks of the voyage.

That changed on the 17th of January 1804. On that date, the captain testified, “a heavy Gale from the northward and westward … blew us off the coast again and continued heavy Gales from the northward and westward until Saturday the 21st .”

For a day they enjoyed fair winds again, as they found themselves nearing Chesapeake Bay.

But only a few hours later, on January 22nd, a northeasterly snowstorm hit the Rockingham, pushed her back south, and pressed her hard against a lee shore. Soon her crew was struggling desperately to keep her beyond the breakers.

Captain Adams reported:

“… a Heavy Gale the wind about NE bent our cables, close leafed our Topsails & [illegible] up our Foresail[,] the Gale still Increasing and snowing tremendously…. 11 AM saw the land on our lee beam close on board[,] then wore ship and stood to the southward….”

As Adams continued, he recalled that the Rockingham “… just cleared the breakers, continued on to the south and nearly in the breakers the sea making one continual break over us until ½ past 4 PM.”

At that point, he testified, “finding it impossible to keep off any longer,” he made the decision to run the brig onto the beach at Currituck Inlet, a desperate move but the only one he had.

He did so, he said, “for the preservation of our lives and what of our property we could save….”

At the time that Capt. Adams gave his testimony, the Rockingham was still grounded at Currituck Inlet. She was evidently battered and beaten, but must have found a decent place to go aground.

Only nine months later, in fact, a Baltimore newspaper reported that the Rockingham was back at sea.

She had arrived in Portsmouth, Virginia, having sailed from Turks Island, presumably with a cargo of salt. (Baltimore American, 31 Oct. 1804, courtesy of the Maryland State Archives.)

I am not sure why, but I did not find any record of the damage to the Rockingham, its cargo losses, or any potential casualties in the insurance records at the Portsmouth Athenaeum.

The intent of Capt. Adams’ account was clear, however. He sought to convince the insurance company’s appraisers that the brig’s damages were due to an act of God, and thus insured, rather than a result of recklessness or poor seamanship, and thus not covered by the company’s policy.

-5-

A couple months after the Rockingham ran aground at Currituck Inlet, another vessel insured by the New Hampshire Fire and Marine Insurance Co. was also struggling off the Outer Banks.

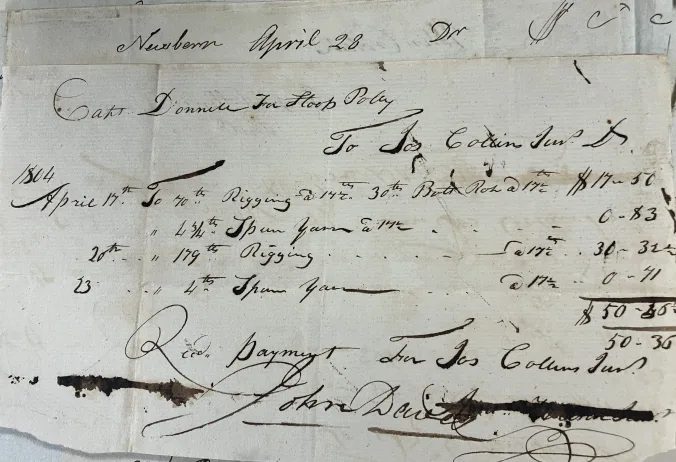

This was the sloop Polly, which sailed out of York, Maine, a seaport 10 miles north of Portsmouth.

In a claims report dated `March 1804, the Polly’s master, Henry Donnell, his first mate Joseph Vondy, and seaman William D. Molton described a voyage from St. Martin to New Bern, North Carolina.

St. Martin, or St. Maarten, is another island in the Caribbean, the northern side of which was a French colony and the southern side of which was a Dutch colony.

At the turn of the 18th century, when the Polly traded there, the large majority of the island’s population were enslaved African laborers.

The Polly sailed from St. Martin on the 4th of March. The sloop enjoyed fair winds until the 24thof March “when the wind blowing a gale … carried away the jib stay . . ., and in about two hours after, carried away the back of the mainsail.”

The three mariners added: “The wind still continuing to blow a gale[,] they sprung the bowsprit at about 12 o’clock.”

On the 25th of March, they were given a respite. “The wind blew fresh, they took in the jib & set the foresail…. The wind [proved] moderate the latter part of the day, they set the jib and shook the reefs out of the mainsail & stood to the Northward….”

Two days later though, a gale hit them with new force, “the wind coming on to blow violently at one o’clock P.M.”

The storm carried away the Polly’s main boom and shredded the foresail “all to pieces.”

The gale kept coming. Even two days later, on the 28th, to quote the claims report again, “the wind continued to blow with great violence & a heavy sea.” Soon the winds sprung the main mast and carried away the cross trees and much of what little was left of the sails.

The Polly was left adrift. The crew spent the next day making a new foresail out of old canvas and repairing the rigging.

They then continued to stagger toward Ocracoke Inlet, on North Carolina’s Outer Banks.

On the 2nd of April, they finally made land north of Cape Hatteras, then ran past Diamond Shoals. By noon the next day, the Polly had reached the bar at Ocracoke Inlet.

They anchored by the inlet that night. The next morning, an Ocracoke pilot sailed out to the Polly and guided her through the inlet and into safe harbor behind Portsmouth Island.

“The current setting strong and the wind being light, they did not get over the Bar until three o’clock P.M. and at four ‘clock came to with the best Bower in Wallace’s Channel, and on the 7th following they arrived at New Bern…”.

At that time, New Bern might as well have been a port in the West Indies, by the look and feel of the place.

The large numbers of enslaved Africans, the multitude of languages spoken along the docks, and the vibrancy of the songs heard in the town’s streets– all gave the little port that feeling. Indeed, to many visitors, the seaport seemed a far outpost of the Caribbean Sea.

The Polly’s crew must have felt right at home, surrounded, as they were, by seamen from far and wide, and of many races and creeds, many of whom, like them, knew the perils of the sea.

-6-

In the New Hampshire Fire and Marine Insurance Co.’s records, I also found three other claims for damages that involved the North Carolina coast. The oldest of those manuscripts, an affidavit dated Nov. 25, 1804, concerned the schooner Dolphin, Ephraim Sutton, master.

That affidavit gave few details but made clear that the Dolphin had been damaged in a storm while sailing from Cape Fear to Portsmouth the previous October.

Another claim, also lacking in detail, concerned a brig named the Reward. According to that claim, the Reward “was cast on shore, at a place called Ocracock, on the coast of North Carolina” either in the last weeks of 1804 or the first weeks of 1805.

A final claim for damages involved a brig called the Forest, another vessel that sailed out of York, Maine. That claim concerned a relatively minor incident, but it provided some interesting details.

In the winter of 1817, the Forest had sailed from Basse-Terre, one of the islands that made up the French colony of Guadeloupe.

At that time, almost 90 percent of Guadeloupe’s population, some 90,000 men, women, and children in all, were enslaved Africans who had been taken from their homelands and forced to work on the colony’s plantations (or were the first generation’s children and grandchildren).

According to the affidavit of Capt. John Perkins, the brig’s master, the Forest left Guadeloupe, presumably having filled its hold with sugar or other goods produced by those enslaved Africans.

She was bound for Portsmouth but was waylaid evidently by storms on the North Carolina coast.

As Capt. Perkins testified, he and his crew “arrived off Cape Fear and saw Bald Head Light House on the 20th of … February, and made a signal for a pilot.”

With a gale rising from the south, none of local pilots responded to the Forest’s signal. Fearful of running the inlet without a pilot, Capt. Perkins ordered the crew to anchor outside of the Cape Fear River’s bar for the night.

The strength of the storm continued to grow throughout the night. By first light, the seas had grown so nasty that the captain “judged it would be unsafe to lay any longer at anchor.”

He decided “that it would be most prudent, and was necessary, for the safety of the Crew, as well as the preservation of the Vessel and Cargo, to slip the Cable… and make … his way in over the Bar, without a Pilot.”

The Forest’s crew “slipped the cable,” abandoning the anchor and chain, and managed to make it over the bar and into a safe harbor.

As I did not find any record of damage to the Forest, I assumed that the insurance claim was for the loss of the brig’s anchor and cable, a relatively small but not inconsequential expense.

Seen in that light, the level of detail in the claims report was meant make it plain that slipping the cable was necessary, given the storm’s dangers, rather than an act of panic or foolhardiness.

-7-

By the time I finished at the Athenaeum, a hard rain was falling. The library’s last patron, other than me, had gone home, and one of the curators and I walked around the library together.

He told me who was who in the old oil paintings, and we talked about the relics, seemingly in every nook and cranny, that had come from sea voyages and distant seaports many years ago.

It was a cozy way to spend a day, listening to the rain and getting swept up in the scenes of shipwrecks and storms that were described in the New Hampshire Fire and Marine Insurance Co.’s records.

At lunchtime, when it was only drizzling, I had walked down to the banks of the Piscataqua, and then over to where, long ago, the waterfront district called Puddle Dock used to be.

Once upon a time, salt marshes and oyster bays were found on that edge of the seaport. Built up over the water, ramshackle fish houses, sailors’ boardinghouses, canneries, and ship chandleries had stood there. Perhaps a brothel, dance hall, and tavern or two, or three, as well.

A sailor’s world. Sea-salt air. Grimy. Raw sewage in the tidal creeks. People of all colors and faiths. People that had been places, most of them. Had seen things. Knew things. Full of life.

The marsh and oyster beds are long gone now, filled in, replaced with a park and a lovely museum and cobbled streets that at least on a cold and rainy day were empty, quiet, and still.

As I walked those misty vacant streets, my thoughts turned back to the records that I had been reading at the Portsmouth Athenaeum.

I thought about all the slave colonies I had seen listed just in the few claims reports that I had been looking at– Grenada, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Grand Turk, St. Maarten and St. Martin.

And I thought of the seaports on the North Carolina coast, which were not that different, their business grounded in shipping the crops that enslaved laborers grew, the lumber they cut, the fish they caught.

As I came out of the rain and into the Athenaeum, I thought as well of the first-person accounts of shipwrecks and storms that I had been reading that morning.

I thought of those sailors on that lee shore at Currituck Banks, looking out over the breakers, eyeing their end.

I thought about all those on the Alligator, the Polly, and the Rockingham, the Forest, the Reward, and the Dolphin. I imagined them watching the waves roll over the decks, the dark and endless sea all around them.

I thought as well of the people on the nearest shores. Perhaps someplace like Ocracoke Island or, closer to where I grew up, Cape Lookout.

I imagined them: the sky still clear, maybe just the first signs of trouble visible on the horizon. I saw them walking along the beach and scavenging driftwood or digging clams or watching over children playing in tidal pools, unknowing, like all of us, of all that was happening out in the great, wide sea.