What do hedgerows and permaculture have in common?

Hedgerows are multilayered, permanent habitats for birds, animals, reptiles, insects, and a host of other living things, providing something for each of them: shelter, habitat, easily renewable resources for building nests and burrows, water, hidden highways and resting areas.

Supporter Spotlight

Permaculture for humans is much the same thing, only the expanded, geared-for-humans type instead of wildlife version. The ideal permaculture — the word was coined from a combination of “permanent” and “agriculture,” with a side of plain “culture” — is pretty much an enclosed, or loop, system.

The idea is to provide for a variety of needs, with everything that can be, recycled and reused.

By mimicking nature, and the way certain plants grow in conjunction with others, humans have figured out how to make hedgerows, or permaculture, work for the benefit of humans.

Working with, rather than against nature, and utilizing practical and thoughtful observation instead of mindless labor, permaculture aims to use less work to gain better results.

Basically, instead of growing one crop over a large area, such as wheat or corn — both products we need and both somewhat counterproductive to grow in small plots of land — permaculture is the method small family farming used to embody.

Supporter Spotlight

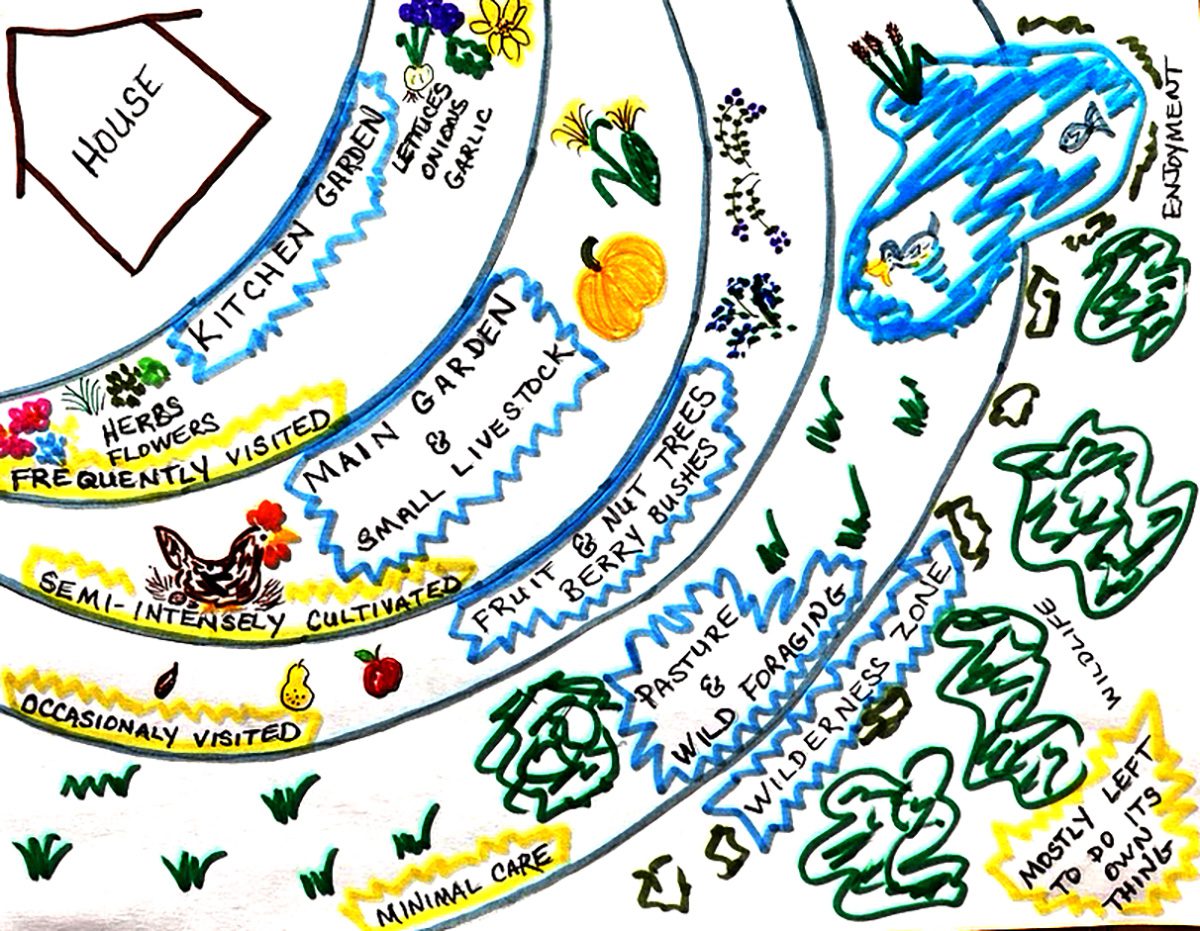

Everything had a place, and was utilized to the fullest extent it could be. Starting with a kitchen garden full of herbs and some vegetables located close to the kitchen door and easily accessible, the areas would expand out into more diverse areas such as a bigger garden, pastures for livestock, fruit and berry orchards, and larger specimens such as nut trees and woodlands.

By observing nature, it could be determined what plants would grow best and where. Manure from the animals would be used to enrich the soil. The movement of water would be catalogued, and ditches and wells and ponds placed in the best areas to sustain drainage and containment. If you’ve ever lived on a farm with a shallow, usually hand-dug well, you know the importance of easily accessible water.

Besides how much water humans need on a daily basis, the stock needs to be watered, and trust me, a herd of cows or horses or pigs can drink a lot of water! The garden needs water. Orchards need water.

Left to themselves, plants will only germinate and thrive in the soil, light, and water conditions best suited to their needs. Humans like to plant things where we want them, to suit our needs. The two are not always compatible.

This is where permaculture comes in.

Permaculture should be designed so everything has more than one purpose. Need a fence? Plant a hedgerow so it can double as a windbreak or as a trellis. In colder regions, a living fence will also reflect sunlight and heat onto plants and livestock during winter months.

Let a rain barrel double as a home for aquatic edibles, and even for fish, then use the water for irrigation.

Use a chicken tractor – a small, lightweight and portable enclosure – to not only protect your chickens from predators and your garden from chickens, but also to enrich the soil.

Called “stacking functions,” this kind of setup allows for multiple purposes for each item.

Establishing permaculture can be a slow process of trial and error, taking into consideration the needs of plants and livestock and humans, and finding the best solution for each.

For instance, just because you love black raspberries doesn’t mean they’ll grow here. The biggest patch of wild black raspberries I’ve ever seen is on top of Mount Mitchell. That’s a good indication those particular plants need cold weather to thrive, so our coastal heat and humidity and mild winters are no good for them. Same with fruit trees. Our climate is not conducive to peaches, and forget about cherries. Apples do marginally better.

Blackberries and figs and blueberries, however, do great on the coast.

If permaculture is such a great idea, and it is, why don’t more people use it? For one thing, it takes time and effort, and it an ongoing process, not a one and done.

Permaculture advocates for no till, which means instead of plowing, less invasive methods are used, and that means less fertilizer, more water conservation, and less soil erosion.

We’ve been taught that in order to have a successful planting, we need to till or plow. Maybe we were taught wrong. Tilling or plowing tears up the soil, loosens compacted soil, and helps with weed control, but we’re learning that tilling or plowing also destroys fungal networks and organisms that hold soil together, not to mention beneficial root mass.

When was the last time you dug into soil and found an abundance of earthworms? Or any earthworms, for that matter?

The purpose of permaculture is to create a mutually beneficial living space for humans and the environment. We’ve lost touch with infinite interactions that exist between humans and the environment. They’re forgotten, these interactions we desperately need to rediscover.

Permaculture also has drawbacks. In giving ourselves a better habitat, we encourage wildlife, which in turn love to feast on our plantings. More plants and bushes and trees mean more insects. More birds. More birds mean more wildlife, each compounding the others. Foxes and snakes and ticks and chiggers, oh my!

Permaculture can be difficult, especially in our area, with our already challenging growing conditions. On the other hand, at least we don’t have rocks and clay soil to deal with.

Someway, somehow, in order for permaculture to work, a perfect balance has to be struck, otherwise all our efforts turn into a chaotic, unbalanced mess.

For more information and probably a better explanation than I can provide, check out these sites:

- The Permaculture Institute.

- Permaculture: A Beginner’s Guide.

- Permaculture – Sustainable Farming, Ranching, Living… by Designing Ecosystems That Imitate Nature – SARE.

- North Carolina State University’s Growing Small Farms.

- Wild Abundance school near Asheville teaches permaculture, carpentry, and earth skills, offering a degree in permaculture.