BUXTON — When the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse was rescued 25 years ago from the edge of the Atlantic, the nation’s tallest brick beacon was relocated with just an ordinary airport beacon in its lantern room.

It could be argued that return of the majestic first order Fresnel lens atop the 1870 lighthouse will be nearly as remarkable a feat as moving the 4,800-ton tower about a half-mile inland. But to the man crafting the replica, it’s the apex of a 40-year fascination with the unique lens that began with another lighthouse.

Supporter Spotlight

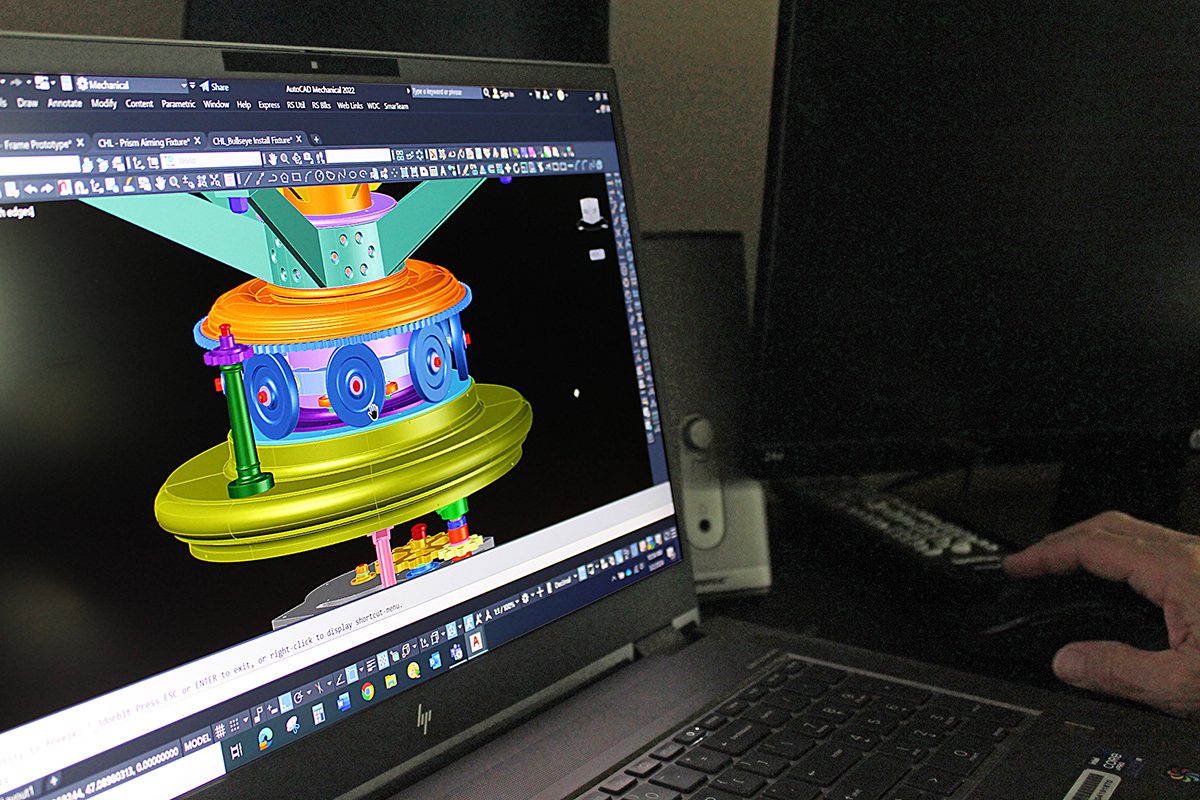

Dan Spinella, owner of Artworks Florida Classic Fresnel Lenses, has been meticulously replicating the design of the original Cape Hatteras Lighthouse lens as part of the current comprehensive lighthouse restoration project. The new prisms, made of a super-strong acrylic, are dyed to exactly match the sea foam green of the glass prisms they’re replacing.

Spinella is likely the only man in the nation, maybe the world, who knows about manufacturing those prisms. But when he visited the 1874 St. Augustine Lighthouse in the 1980s, it was the first time he had been even inside a lighthouse.

“And when I saw the lens, it’s like, ‘Whoa, what the heck is this?’” Spinnella recalled during a recent telephone interview. “I had no idea.”

St. Augustine’s Fresnel lens, the same impressive size as the Hatteras lens, immediately captivated him and set off an unusually productive obsession. Before he knew it, Spinella, who then was and still is employed as an engineer at Walt Disney World, offered to take dimensions and do some drawings to help in the lens restoration.

“Yeah, I went from volunteer to volunteer/business, and it just evolved over the years,” he told Coastal Review, speaking from his Orlando home. “Nothing that I planned; it just kind of worked out.”

Supporter Spotlight

The website of the nonprofit St. Augustine Lighthouse and Maritime Museum credits the efforts of the Junior Service League of St. Augustine and others, including Spinella and Joe Cocking, the lampist who had later saved the fixed Fresnel lens atop Bodie Island Lighthouse, for restoring its lens after being damaged by a vandal’s gunshots.

After working on the St. Augustine project for about a year, Spinella, a professed history lover, said he had learned a lot about how Fresnel lenses worked. He started with engineering books from the 1850s he had located that were written by Scottish lighthouse engineer Thomas Stevenson, the father of writer Robert Louis Stevenson.

He found optic formulas that explained the lenses’ ability to refract and reflect light, allowing him to design a cross-section of the lens “perfectly,” he recalled. And while he kept learning, he kept going. Next, he volunteered at Ponce Inlet, Florida, then continued the work by helping to replace parts at other lighthouses. All along, he was experimenting with cast acrylic, machined acrylic.

“I tried several different ways of getting these prisms made,” Spinella said. “Then in 2004, I started making reproductions.”

Around that time, John Havel, then a graphic designer at the Environmental Protection Agency’s campus in the Raleigh area, had developed a fascination with the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. After focusing on its original blueprints and plans and collecting old photographs, Havel recounted in a recent interview, he was soon doggedly researching deep into historic lighthouse archives.

“When you study the lighthouse, you see that it is this magnificent, incredible, amazing example of American Victorian architecture,” said Havel, who is now retired from the EPA and the owner of Havel Research Associates in Salvo, a Hatteras Island village north of Buxton.

The Hatteras lens, as well, is an extraordinary piece of art.

“Every first order lens is different,” he said. “There are no other lenses identical to the Cape Hatteras lens, or to the Bodie Island lens, or to the Currituck Beach Lighthouse lens. Every single factor except the height and circumference of the lens is different.”

There are a total of six orders of Fresnels lens, with the smallest able to be slipped into a purse.

A couple of years into his research, Havel recalled, he was visiting the office of the historian with Cape Hatteras National Seashore and noticed a small prism on his desk.

“And he started telling me about this guy down in Florida who made these lenses and wanted to offer a replicas lens through the park service for Hatteras,” he said.

But it wasn’t until 2015, after speaking about the lighthouse restoration at the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society Keepers Weekend, that Havel flew to Florida meet Spinella.

To put it mildly, Havel was impressed. In the years since, as a member of the Lighthouse Society board, and as a dedicated volunteer, he encouraged the National Park Service to tap Spinella’s expertise. Today, Havel is employed as a historic preservation consultant for Massachusetts-based contractor Stone & Lime Historic Restoration Services Inc., as well as an assistant and consultant for Spinella.

The $19.2 million restoration project, of which Spinella is being paid about $1.25 million, began in early 2024 and is expected to be completed by late spring or early summer 2025.

“He’s doing this entire thing,” Havel said of the skilled lens maker. “He’s doing this by himself, while he has a full-time job at Disney … He’s a genius.”

Initially, the park service was considering the possibility of restoring the original 1853 lens, the remains of which are on loan to the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras, a part of the North Carolina Maritime Museums system, which under the state’s Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

“Yes, we did talk about the option of doing that, and consulted with lampist Jim Woodward,” said National Park Service Deputy Chief of Cultural Resources Jami Lanier in a recent interview. “It was determined that it would probably not be feasible to do that for a couple of reasons (including) some issues with the frame of the lens not being exactly aligned to be able to accept the new prisms. And so it was felt that there could be some potential damage to the frame, or the lens itself, if that was attempted.”

Then there was the cost of replacing all the prisms — only 268 of the 1,000 or so prisms were salvaged — which “would have been astronomical,” she said.

The lens had been removed from the 1853 lighthouse, which was a taller version added to the 1803 tower, and installed in the1870 lighthouse, Lanier said. The lens was removed again in 1949, and in 1953 the lighthouse became part of Cape Hatteras National Seashore. But in the years before and after World War II, the lighthouse was essentially abandoned and the lens was vandalized, she said.

Lanier explained that Woodward and his team had removed the original pedestal from the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in 2006, put it together at the museum with the remains of the lens stored in a park facility on Roanoke Island.

Lanier said that the park service also discussed the potential of retrofitting the original lens with acrylic or glass replacements.

“You know, we went through all those discussions,” she said. “But in the end, it was just decided not to retrofit the original lens either way, and we knew if we were going with the replica that it would be acrylic.”

Indeed, it would cost four to seven times more to make the replica prisms in glass, Spinella said. Some prisms in glass restorations he has done cost $4,000 each, and some were as much as $20,000 each. And multiplied by 1,008 prisms, that could mean millions of dollars. Plus, glass is heavier and would put an additional load on the structure, he said. The original lens weighed 4,500 pounds, while the reproduction will weigh a mere 1,600 pounds.

A first order Fresnel lens, which is shaped like a beehive, is 8 1/2 feet high and 6 feet wide. Not only is the acrylic lighter, Spinella also used anodized aluminum frames that are a third the weight of bronze. Also, the aluminum will not deteriorate or tarnish, but it looks the same as brass except it’s not quite as shiny.

“Polished brass looks absolutely beautiful when I install them, but I can go back a couple months later and they look terrible just because of the humidity and condensation in the lantern room,” he said.

In 2009, Spinella worked with Woodward, who has worked on more than 400 lenses, to measure the lens, and he went back to his workshop and created a 3D model of it. During the intervening years while the park service mulled over having a replica lens, Spinella had continued his experiments, perfecting his acrylic prisms. The initial cast acrylic lacked the quality he wanted, and he eventually settled on optical acrylic.

“It’s a very high-quality acrylic,” he said. “I mean, they use it in fighter jet windows, and it’s UV stable, and it’s easy to machine, sand and polish and it can be tinted.”

Optical acrylic also is clearer than glass and transmits more light, he added. Although it’s strong and durable, it doesn’t last as long as glass.

Importantly, the reflective and refractive ability is nearly the same, with only slight differences.

“It actually bends light a little,” he said. “It’s got a slightly lower index of refraction, so … I’ve adjusted the formulas and adjusted the profile of each prism and shape of curvatures according to the refractive index of acrylic.”

A modern Fresnel-specific LED bulb, installed on a little stand on the pedestal, is hooked up to a sophisticated controller that, at $10,000, costs more than the $8,000 LED, Spinella said. But even with the light source now drastically different than the original kerosene oil lamp, the prisms are in the same arrangement around it.

“That lamp was a flame or omnidirectional light, so it spread 360 degrees spherically in all directions,” Spinella explained. “So that was the purpose of these lenses, to capture as much of that light as possible.”

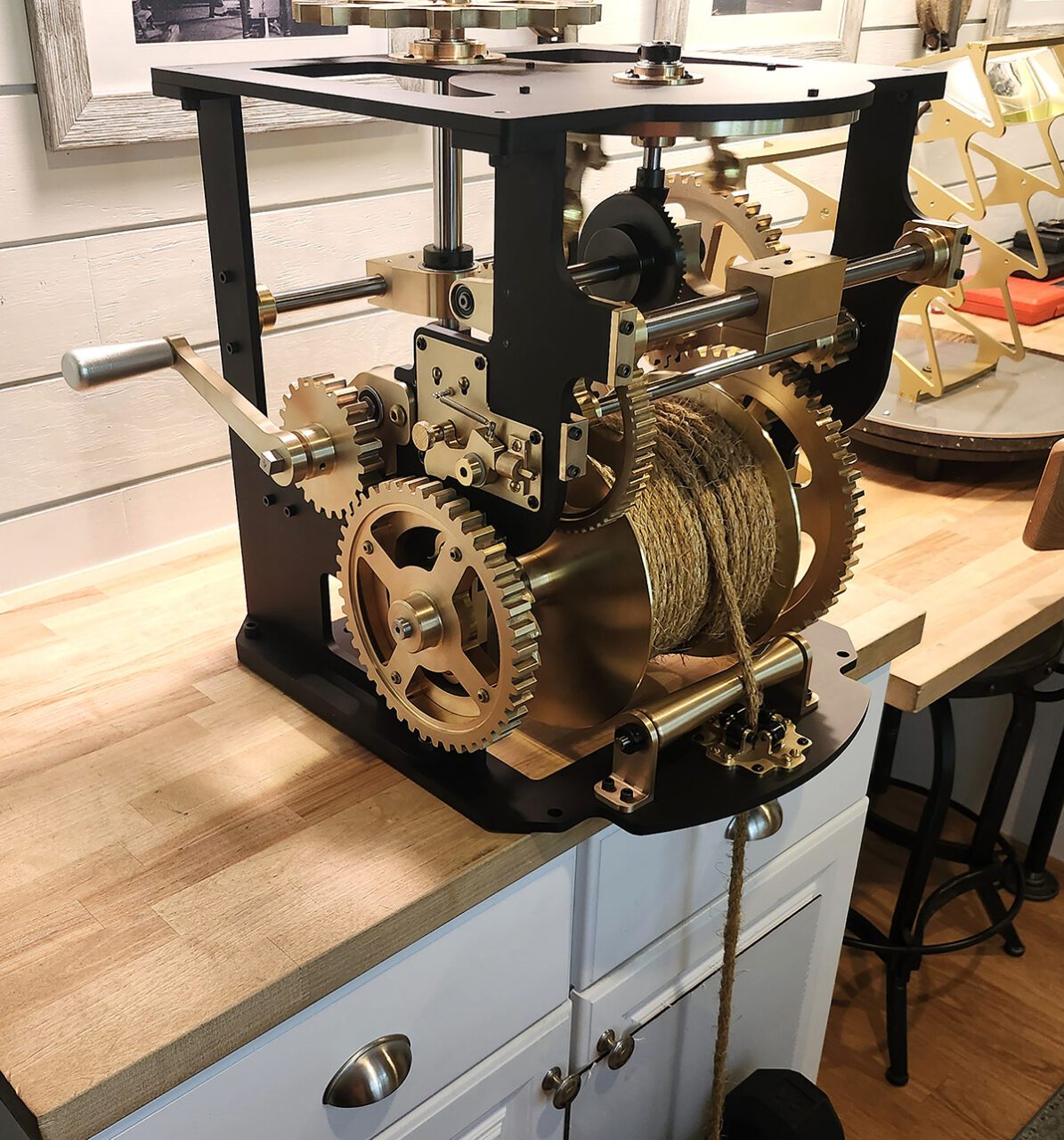

As Havel noted, another engineering feat that Spinella accomplished was his replication of the lens’ clockwork mechanism, which was based on the 1853 original at the Graveyard museum. There are no known photographs or even descriptions of the lens and its machinery, he said.

“Dan has replicated that with all new gears, metals and whatever (mechanisms) rotated the lens so that it would flash out to sea,” Havel said.

The clockwork had been run by hemp rope, which was extremely strong but messy.

“Hemp sheds,” Havel said. “Dan found synthetic rope that looks the same but isn’t hairy like hemp.”

The rotating beacon’s original flash pattern of every 10 seconds, instead of the former 71/2-second burst, is being restored, and it will continue to be visible for up to 20 miles. As Spinella explained it, each minute the mechanism rotates a quarter turn, a full rotation takes four minutes, “And what that’ll give you is a 10-second flash interval,” he said.

Each lighthouse has its unique flashing characteristic and daymark, which are listed for mariners by the U.S. Coast Guard.

Once Spinella and Woodward reinstall the beacon — probably in June — there will be a day when people who climb to the top of the tower will be able to see for themselves the mesmerizing beauty of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s First Order Fresnel Lens.

Spinella said he has modified the lens with modern elements, but he said it’s still correct to consider the lens a replica because it follows the original design. For instance, while the clockwork mechanism and chariot wheels that rotated the lens are still part of it, the real rotation will now come from a 1/3-horsepower electric motor operated by a controller.

“I’ve done some things that make it more durable and more modernized,” he said. “But you really won’t see any of it.”