Undergraduate students who spent their fall semester studying Currituck Sound may have broken new ground in understanding the effects of controlled burns on a marsh island.

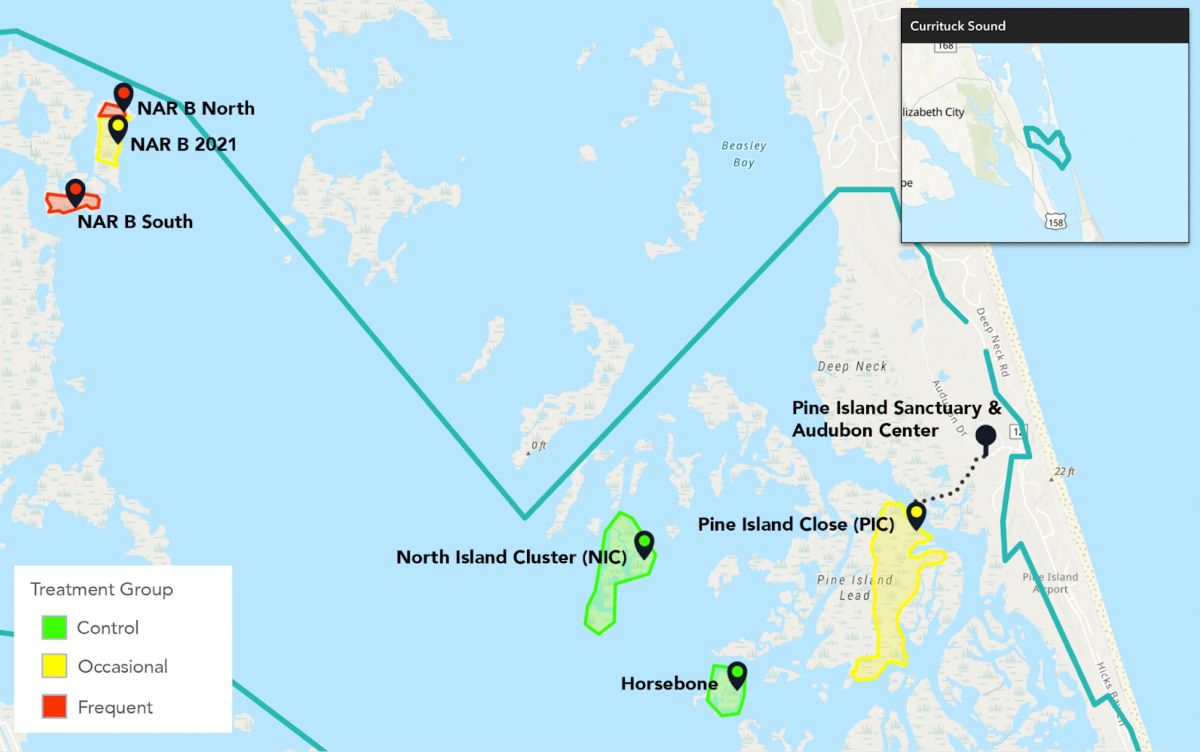

For the project, students compared vegetative changes to the marsh islands with the Audubon Pine Island Sanctuary and Center in Currituck County that have no history of recent fire, islands that are occasionally burned, and islands that have had frequent controlled burns.

Supporter Spotlight

The students presented their findings “The Sound of Change: Responses to Controlled Burning and Other Changes in the Currituck Sound,” Dec. 12 as part of the monthly Science on the Sound lecture series at the Coastal Studies Institute, or CSI, on East Carolina University’s Outer Banks Campus.

The students conducted the research project as part of the Outer Banks Field Site, or OBXFS, a semester-long, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill undergraduate program hosted each fall by CSI.

Controlled burns are part of a fall tradition that existed well before the first European set foot upon the North American continent and “has deep historical roots in the South, where the practice was quickly adopted from the Indians by early European settlers,” according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service research.

While there have been a number of studies examining how a controlled burn effects a marsh, delving into a fire’s impact on invasive species, soil accretion, plant diversity and potential of endangering some animal species, this research takes a different approach.

The study “was one of the few that worked in brackish marshes, and the students talking to stakeholders and users of the marsh about the changes they perceived is also something that’s, I think, unique to the study,” Outer Banks Field Site Director Lindsay Dubbs said during the presentation.

Supporter Spotlight

The students included a human dimension and interviewed people who use the Currituck Sound frequently about the environmental changes they feel have taken place.

For their field work, the students traveled to marsh islands within the boundaries of the Pine Island site and compared the effects of controlled burning on marsh vegetation.

The islands were divided into three groups. The control islands had “no historical data of any burns happening,” explained sophomore Lily Bertlshofer. “Our occasional sites were last burned in 2021 and our frequent sites have data being burned every year.”

The study was designed “to look at how controlled burns impact the allocation resources within marsh plants and soils, the impacts of controlled burning on the vegetation community of marsh and what the implications for marsh resilience are,” Berlshofer said.

The study confirmed that the long-established practice of prescribed burns benefit vegetative diversity in marsh inlands.

At first glance there does not appear to be a significant difference in plant diversity among the three areas.

“We found that there was no statistically significant relationship between species richness and burn frequency,” said Veronica Cheaz, a sophomore.

That finding was expected. Because the number of plants that can live in a salt-to-brackish environment is limited, diversity is relatively low.

“Generally, we found low species richness at all of our plots, which is not very surprising,” Cheaz said. “We have a brackish marsh in the Currituck Sound, and there’s not going to be very many species.”

What the study did identify, though, was how effective controlled burning of a brackish marsh could be in maintaining the habitat.

“We also looked at salinity tolerance,” Chaez said, which “is going to be influential in determining how effective these sites are at adapting to environmental stressors like sea level rise and a rise in salinity. We found that occasionally burned sites had the highest scores compared to our control sites, and we hypothesized that this is because occasionally burned sites have a balance of the disturbance periods and restoration periods that allows salt water species to move in.”

There was at least one surprising finding. When the living root systems, or the biomass, of the three sites were compared, the frequently burned areas have statistically greater biomass than either the control or occasional burn areas.

Pointing to a graph showing more than double the biomass of an occasional site, senior Katelin Harmon, majoring in environmental studies and political science, described the finding that “frequently burn sites were much higher,” as “one of our most interesting findings…There’s much stronger root systems in our frequently sites.”

Verdant and complex, the Currituck Sound marsh is somewhat unique. The nearest saltwater source is Oregon Inlet some 55 miles to the south of the study area at the Pine Island Audubon site. The salinity there is typically under 3 parts per thousand, or ppt, and at times lower.

“The low salinity makes these places special, and we refer to that as an oligohaline environment,” junior Thomas Ferguson said during the presentation.

Currituck Sound has not always been an oligohaline, or a low-salinity, environment. Throughout the colonial period and into the early 19th century, there were two inlets on the north end of the sound. Currituck Inlet across from Knotts Island was open until the 1730s. New Currituck Inlet just to the south, opened soon after that, closing in 1828. Until New Currituck Inlet closed, the north end of the sound was a high-saline brackish marsh.

With the closing of the inlets, Currituck Sound transitioned to an oligohaline marsh and migratory waterfowl began arriving by the hundreds of thousands, creating a hunter’s paradise.

“In 1828 the Currituck Inlet, at that time composed of salt water, was closed by a storm and the vicinity gradually became fresh water. This change allowed vegetation such as wild celery and eel grass to grow on the marsh bottom and this new vegetation attracted wintering fowl in greater quantities than before,” The National Register of Historic Places noted in its assessment of the Currituck Shooting Club.

The Currituck Shooting Club, founded in 1857 “by a group of business men in New York City,” the assessment wrote, was the first of numerous hunting clubs that lined the shores of Currituck Sound. The building was completely destroyed by fire in 2003.

The Pine Island Club was formed in 1910. In 1979 the last private owner of the club, Earl Slick, a Winston-Salem developer, donated 2600 acres of marsh and uplands to the National Audubon Society. In 2009 Audubon North Carolina assumed full-time responsibility for the managing the club.

Hunting is still allowed on the property, but according to at least one of the hunters the student researchers interviewed, it falls well short of what it had once been like.

“It really doesn’t have any ducks compared to when I was young, when I was your age, this place had ducks. This place doesn’t have anything anymore,” the researchers were told.

In a question-and-answer session following the presentation, Pine Island Site Manager Robbie Fearn noted that the statistical biomass findings at the frequently burned areas was inconsistent with what was visually happening.

“I’m at the Pine Island Sanctuary,” he said. “The areas that are frequently burned from my lived experiences are falling apart, and yet the data says that for longer term management, frequent burning may be better… Is it a question of the plants are responding to the frequent burn by trying to survive and creating more below-ground biomass.”

For Fearn, who was very complimentary of the work the students did, the inconsistency between what he has observed and what the statistics say is a jumping off point for much needed further research.

“The work that these students have done have really set us up to dig in and figure out how best to manage these marshes in the sound and I’m very thankful for their work,” he said.

Coastal Review will not publish Jan. 1 in observance of New Year’s Day.