The acclaimed coastal scientist Orrin Pilkey, who died at the age of 90 on Sunday, had more stories than an old wet dog.

A few years back, we were sitting around the kitchen table in the retirement community in Durham, North Carolina, where he lived in later years. It was a comfortable apartment, messy with books and papers and walls filled with Orrin’s impressive collection of Indian arrowheads. Importantly, it was close to Orrin’s beloved Duke University, where he taught coastal science for a half-century and still had a coveted parking space in the faculty lot.

Supporter Spotlight

Orrin was telling me how he grew up in Richland, Washington, near the Hanford Reservation Reactor.

“We used to play in the puddles after it rained,” he said. “It drove my mother crazy. When the whistle went off, she would rush to the door and call us kids inside because they were about to release a radioactive cloud. We liked to say the dogs in Richland all glowed at night. It was great fun growing up there.”

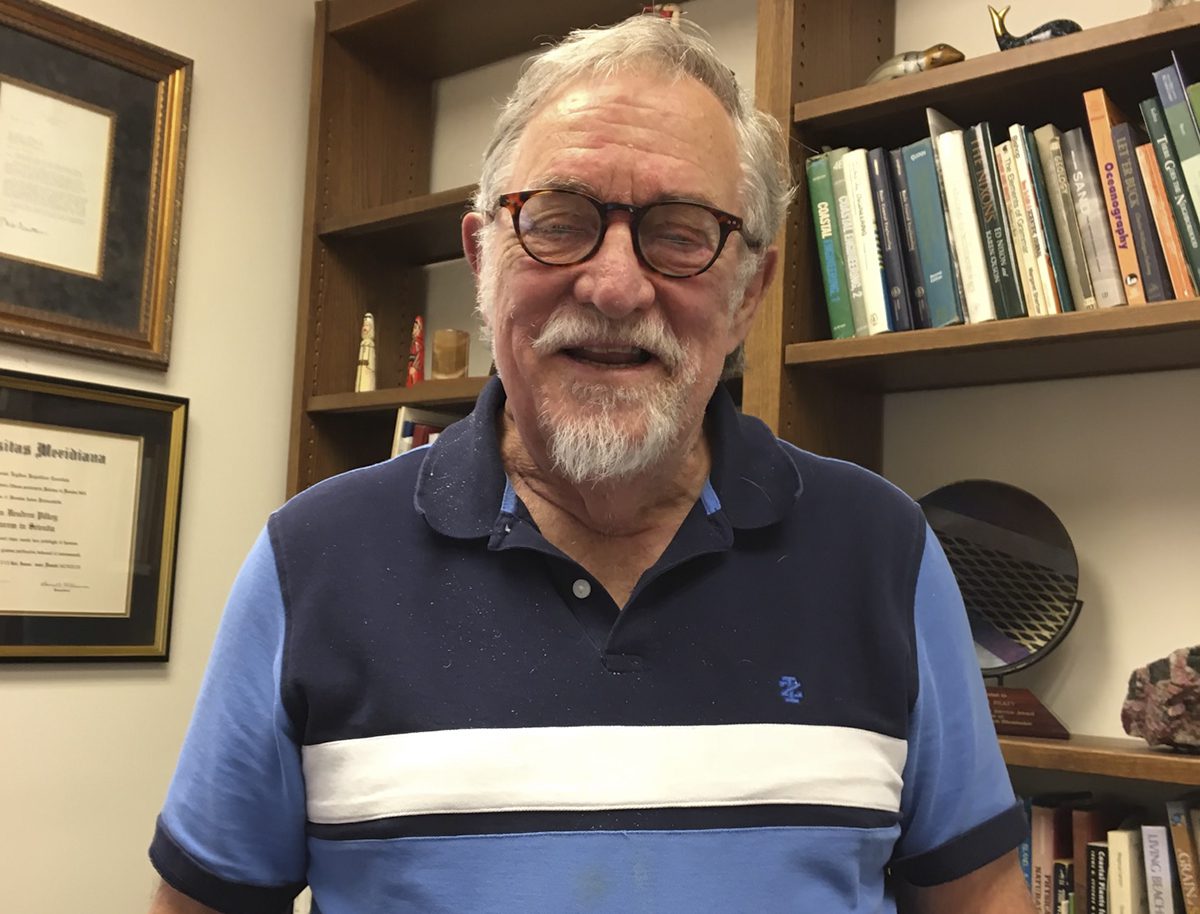

In a 2019 book, “The Geography of Risk, Epic Storms, Rising Seas, And The Cost of America’s Coasts,” I described Orrin this way: “Pilkey is a short, square hobbit of a man, with an unruly gray beard and a disarming sense of humor. Depending on your point of view, he is either a prophet or the antichrist of the coast.”

I worried a little that Orrin might be offended, but when an acquaintance brought up the description, he roared and said, no, he loved it. It was exactly right.

Orrin was maybe 5 feet, 4 inches tall, and had an impressive belly. He swore to me that he used to run marathons and had broken three hours at the Boston Marathon. I was a decent enough runner back in the day and had struggled to break three hours, which is considered the standard separating real runners from hobby runners.

Supporter Spotlight

Like many of his stories, it verged on the unbelievable. But Orrin was like that, always surprising, a prolific and important writer of books on North Carolina and other coasts, a provocative critic, a generous, dedicated teacher, and as Rob Young, one of Orrin’s former students and the head of a coastal science program at Western Carolina University, wrote in a LinkedIn post, “He was funny as hell.”

You had to work hard to not like Orrin. Over a quarter-century, I watched developers and engineers scream invective at him for challenging the way they stacked fragile beaches and sand dunes with ever-larger investment properties. But I also reveled in how Orrin could disarm even his most hostile critics with an impish grin and a joke.

Once, back in the winter of 1998, I was showing Orrin around some of the new development in Corolla, on the northern Outer Banks. We had just finished emptying our over-caffeinated bladders behind some wax myrtle, when one of the developers roared onto the gravel lot in his Caddy and began screaming at us for violating private property. This lasted roughly a minute when suddenly he stopped, stared at Orrin, and exclaimed, “Hey, I know you. You’re that Pilkey guy.” Orrin smiled and marched over to the car. By the time it was done, the developer had Orrin’s email and was his next best friend.

Some of the engineers at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers bitterly criticized Orrin’s science and complained that he was training a cadre of young “Pilkeyites,” who would ruin the coast. By ruin, I think they meant put a halt to the development and the Corps’ costly beach replenishment projects, in which they pump millions of cubic yards of sand onto eroding beaches to save the property lining the shoreline. Pilkey correctly pointed out that those projects were mere Band-Aids, lasting a few years before the next storm came along and washed the sand out to sea. “It’s madness,” he told me many times. “Absolute madness.”

A Florida engineer complained that Pilkey “got all of the students who got 1600 on their SATs,” and then indoctrinated them in his ways. I loved that. They just didn’t know what to do with Pilkey.

“My approach to coastal science and management is very different from his,” Young wrote. “But, my approach to life is not. My dad died when I was 21. Orrin was the closest thing to a father I had for the last 40 years. He gave me my current position. I owe him so much.”

Orrin got his Bachelor of Science in geology at Washington State University and his master’s in Montana and figured he would become an expert on mountains and shale. During summers, he worked as a smoke jumper and manned a fire tower deep in the forest. Instead of staying out West, he picked up his PhD in coastal science at Florida State and became an expert in sedimentology.

He lived for a time on Sapelo Island, off the coast of Georgia, where he attended church in a ramshackle chapel with the Gullah Geechee. “Hey, I really like the singing, Pal,” he told me. He called everyone pal. Later, he researched the abyssal plain, a gaping mud hole in the ocean so deep sunlight does not reach the sea floor.

In the mid-1960s, Duke took a chance and hired Orrin to start a marine geology program. “It was a big leap,” he said. “They were taking a big chance.”

Over the years, he helped to train thousands of students now scattered across the land. Early on, he was approached by Paul Godfrey, a marine biologist working for the National Park Service on Cape Lookout, and asked to sign a petition protesting a reckless development along the coast. “I was new and didn’t sign,” he told me, with a frown. “It was a big mistake, one of the biggest mistakes I ever made.”

In time, he would become one of the loudest critics of what we were doing to our coasts, penning scores of opinion articles and essays, often appearing on radio and television. Duke was his local podium, but he traveled the nation and the world, spreading the gospel of Pilkey, which might be summed up this way: Preserve as much as possible of what we have left at the coast, stop hardening eroding shorelines with groins and sea walls and, above all, allow the barrier islands to keep moving, the way Mother Nature always meant.

Orrin wasn’t impressed with many of the incremental policies being implemented to protect the coast. He believed they were too little, too late. In time, he became a national advocate for retreating from the coast as the seas rose and storms became larger and more destructive. His position felt impractical to some coastal geologists, who knew that developers, politicians and property owners would fight efforts to remove them. Far too much money was at stake.

When I asked him if he was becoming out of step, he shrugged and told me “I’ve always been out of step.” And then he laughed.