Warming sea temperatures fueled significantly more intense hurricanes between 2019 and 2023 and force-fed nearly a half-dozen storms into Category 5 strength, including two this current season, according to a newly released climate study.

Human-caused climate change has, on average, boosted peak, pre-landfall Atlantic hurricane wind speeds by 18 mph over the last six years, said Dr. Daniel Gilford, lead author of the study published in the journal Environmental Research: Climate.

Supporter Spotlight

“Every single storm we studied in 2024 had an intensity increase of these warmer sea surface temperatures by something between 9 and 28 miles per hour,” Gilford said during a webinar Tuesday afternoon.

A total of 11 storms have churned over warming waters this Atlantic hurricane season, which ends Nov. 30.

Gilford, a climate scientist at Climate Central, a nonpartisan, nonprofit independent group of scientists who research and report the effects of climate change, said that between 2019 and 2023 and over the course of this hurricane season, storms have strengthened over waters as much as 2.5 degrees warmer because of global warming.

Scientists found the faster rate at which hurricanes are spinning equates to an average of about one category higher on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. This scale does not measure hurricanes’ other potential destructive factors, including storm surge, which is also being exacerbated by rising seas, and rainfall.

A companion study also released Wednesday by Climate Central found that Hurricane Helene’s peak wind speeds were made about 13 mph more intense because of climate change.

Supporter Spotlight

The difference is a “tiny bit lower” than Gilford’s findings, “but very much in the same ballpark,” said Dr. Friederike “Fredi” Otto, a senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College London and lead of World Weather Attribution, a team of researchers from several European-based institutions.

Otto said the companion study, “really shows that these two completely different lines of evidence show us the same thing.”

The study led by Gilford traced data from the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship, or IBTrACS, which provides global cyclone track information, and the National Hurricane Center’s GIS archive to analyze hurricanes back to 2019.

Researchers used observations and reanalysis from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s optimum interpolation sea surface temperature, or OISST, which is a long-term climate data record, and combined climate models to look at how sea surface temperatures are changing.

The companion study looked at stochastic models, which use mathematics that incorporate randomness and uncertainty to simulate hurricane behavior, including intensity, track, and landfall location.

From a scientific point of view, Otto said, the changes brought on by global warming show that a storm that might have been a Category 4 over cooler sea surface temperatures is now building up to a Category 5, the highest on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale.

“That makes a huge difference and I think that can also make a huge in how we communicate about the impact of climate change because, as we’ve seen, quite tragically this year, people died and there are huge death tolls when extreme events happen that people have not experienced before,” Otto said.

Thus was the case when Hurricane Helene swept up the Gulf Coast, making landfall Sept. 26 in Florida’s Big Bend region before barreling north through western North Carolina. More than 230 people across six states died as a result of the storm, one that gutted mountain towns, ripped away roads and caused more than $50 billion in damage.

Even though there “were really good warnings,” people in the Appalachian region had not experienced such an extreme event so they did not know what to do with the warnings, Otto said.

“I think this, that we see now, again and again, that records are broken, that wind speeds are higher than ever before, rainfall is higher than ever before. We really need to use that to make sure that people don’t die,” she said.

Otto added that it may be time to discuss whether to add a sixth category to the Saffir-Simpson scale, “just so that people are aware that something is going to hit them that is different from everything else they’ve experienced before and therefore more dangerous.”

Hurricanes Beryl and Milton were identified as the last of five storms that strengthened into Category 5 storms because of climate change, according to the study led by Gilford.

NOAA predicted earlier this year that there was an 85% chance this Atlantic Hurricane Season would be above normal.

Hurricane Beryl first formed on June 28 and broke a series of records this season.

It was the farthest east that a hurricane had formed in June, the first Category 4 storm to form in the month of June and, on July 2, it became the earliest Category 5 hurricane on record.

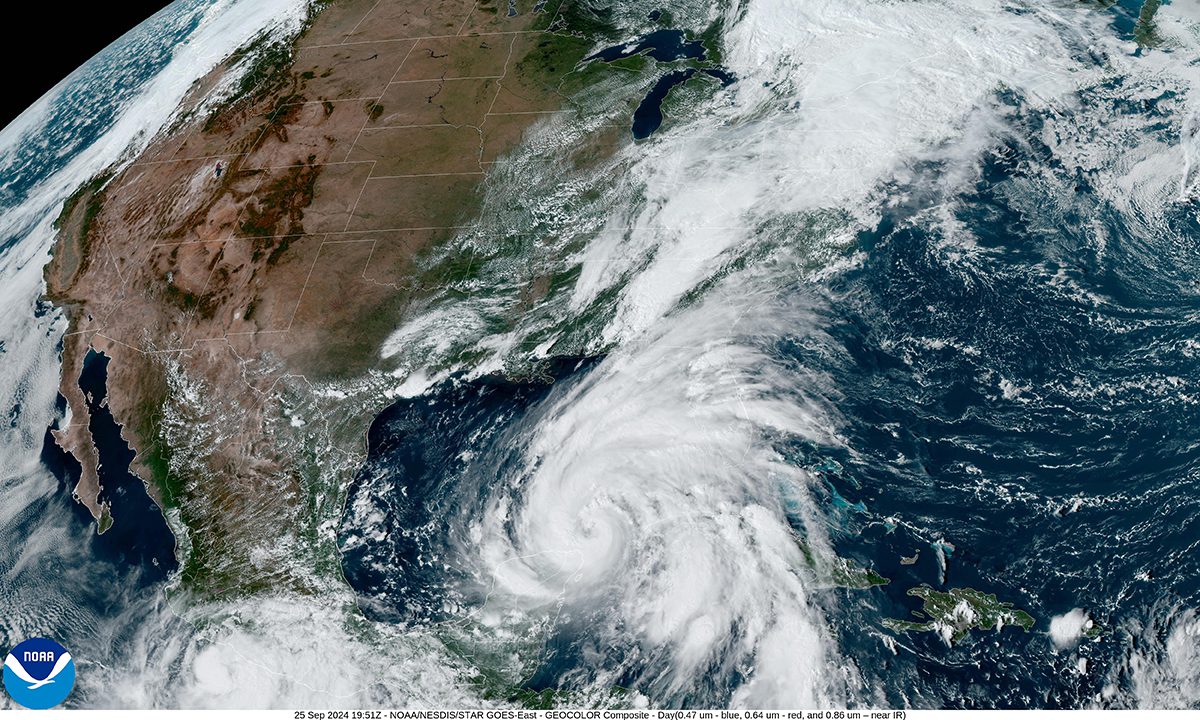

A little more than three months after Beryl made its third and final landfall – the last in Matagorda County, Texas – a monster Hurricane Milton seemingly filled the Gulf of Mexico as it roared toward Florida’s Gulf Shore. The speed of intensity at which Milton grew brought tears to longtime meteorologist and NBC 6 South Florida weatherman John Morales, whose live forecast went viral after he choked up reporting that the storm’s air pressure had dropped 50 millibars in 10 hours.

Morales, one of the speakers taking part in Tuesday’s webinar, noted that over his 40-year career he was seeing more hurricanes go through extreme, rapid intensification cycles in recent years, compared to years past.

“For all I know we might have four hurricanes in a year, but if 50% of those are becoming Category 3, 4 and 5, then we’ve got a problem because a greater proportion of them are becoming the very dangerous ones,” he said.