The federal agency that identifies offshore wind energy areas is in the early stages of siting another possible commercial lease sale for the East Coast.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management held an open house last week at the Crystal Coast Civic Center in Morehead City, the first in the multiyear, multistep planning process for Central Atlantic 2. BOEM manages development of the U.S. outer continental shelf energy, mineral and geological resources.

Supporter Spotlight

BOEM Project Coordinator Seth Theuerkauf explained that the agency has just begun the work to identify lease areas in the Central Atlantic region.

“We’re at the call area stage, the first step of our process,” Theuerkauf said, adding that what’s really driving the effort is the remaining offshore wind energy needs for North Carolina and Maryland.

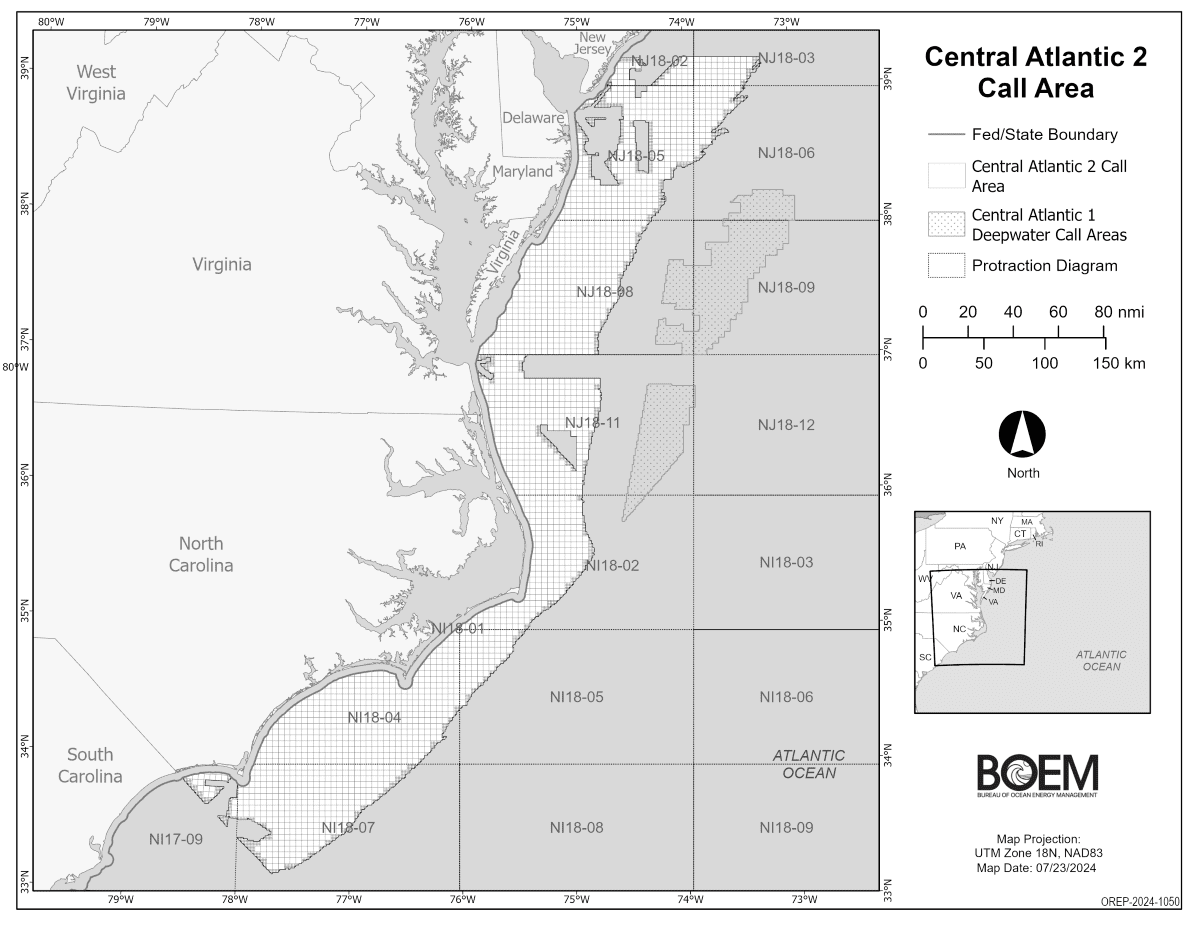

Officials on Aug. 22 published in the federal register the call area, which is 13 million acres off the coasts of New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina, and launched the 60-day public comment period that ends Oct. 21.

BOEM has scheduled open houses over the coming weeks in the other states plus a virtual meeting from 6 to 8 p.m. Oct. 2. Register for the Zoom meeting online. This meeting will feature presentations and offer a chance to comment.

North Carolina has a goal for 8 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2040 and need 3 more gigawatts of lease area to meet that goal. This process is intended to try to identify those lease areas – about 185,000 acres — that would help North Carolina meet its goals. Gov. Roy Cooper’s office established the goal in 2021 with executive order 218.

Supporter Spotlight

The call stage looks at a broad area, between 3 nautical miles offshore, where state and federal waters meet, “all the way out to 60 meters, which is basically as deep as you can go and have fixed foundations for offshore wind turbines,” Theuerkauf said.

The intent of this stage is to gather as much information as possible to help identify resource or use conflicts in the call area, Theuerkauf said.

BOEM is building the project on the momentum of the wind energy lease sale that took place in August and included two areas, one off Virginia and one off of Maryland and Delaware. The call area for that sale included offshore Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina, between the Virginia line and Cape Hatteras.

For the second round, Theuerkauf said the boundaries are being extended.

“The state of North Carolina indicated interest in looking at areas further south from Cape Hatteras, down to that South Carolina, North Carolina border. Again, we’re really looking for enough lease area to meet those state goals. We know there’s a lot of conflict, there’s a lot of usage, military activities, vessel traffic, natural resource considerations. And that’s really the information we’re trying to gain to identify and narrow.”

Some of the activity in the ocean that could conflict with an offshore wind energy area are military training activities and are areas that are important to vessel traffic, called fairways. The Coast Guard is working through the process to identify fairways and once those are established, these paths will be “no-go zones for offshore wind energy.”

Theuerkauf said other conflicts include fisheries, in terms of avoiding areas where there’s higher levels of fishing activity.

In all, “there’s really a whole lot that goes into the process” of determining an offshore wind area, Theuerkauf added. “We’re partnering with NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science to basically build a spatial model that takes all that information into account and is able to tell us on this sort of red-yellow- green scale, where are those areas that are best or worst based on all of that information.”

He said there’s also an expert focused on viewshed considerations. “We typically have applied coastal setback” for viewshed, Theuerkauf said, which is basically establishing a distance that wind energy areas had to be from land. “The state of North Carolina shared that 20 nautical miles is their recommended coastal setback.”

Theuerkauf said the next stage in the process is to identify draft wind energy areas. That process is essentially to narrow down the call area to smaller, less-conflicted areas. Those draft wind energy areas would go back out for public comment.

Along with Theuerkauf to explain the spatial modeling were Bryce O’Brien and Alyssa Randall with NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science. Randall said they gather lots of data on all possible conflicting uses and categorize that information into submodels to run a suitability model to determine the best spot is to site a lease.

O’Brien said the submodels — constraints, national security, industry, fisheries, wind, and natural and cultural resources — are combined and that’s how they determine the area with the lowest number of conflicts.

Mid-Atlantic Regional Council on the Ocean, or Marco, Communications Director Karl Vilacoba, said while gesturing to a map of the Central Atlantic region that MARCO has online a free, publicly accessible mapping site that shows “pretty much anything you can imagine at sea, including where vessel concentrations are, fishing grounds, sensitive habitat, real life distributions. People can use the portal to see how all these things relate to each other, and in some cases, conflict with one another, so that people in ocean management worlds can make better informed decisions.”

He said that the portal “gives the public a chance to look at a lot of the same information that the agencies are using to make their decisions.”

MARCO Executive Director Avalon Bristow added that while MARCO is not a program of BOEM, it works in partnership with BOEM and other federal agencies, states and other stakeholders “who are interested in the ocean to present information that might be useful to understand how decision making is made offshore.”

From a fisheries perspective, Thomas Moorman, a scientist with BOEM, said that different types of fisheries-related information is taken into consideration that would affect the suitability for a potential site.

For instance, data from the National Marine Fisheries Service that illustrates where commercial fishermen are going for specific species is incorporated.

“We look at like density of areas where fishing is occurring, and we do that by species,” which helps inform siting an area. “If we think about siting this area, what are the main fisheries that would occur here? And how does a potential sale interact with the fisheries that occur here?” Moorman continued. They take that information to form the question “is this an area where we should or shouldn’t consider for a lease sale?”

BOEM Marine Biologist Jeri Wisman said that when it comes to how offshore wind projects affect endangered species, she spends a lot of time explaining the impacts to marine mammals, particularly the related noise and vessel traffic, and mitigation strategies.

Another consideration, BOEM environmental specialist Lisa Landers explained, that is taken into consideration is how an offshore wind energy lease could impact cultural resources.

With the open houses and public comment period, “We’re looking for information, any recommendations regarding areas that we should avoid — or should we provide consideration to specific setbacks or buffers — anything that should be taken into consideration,” and that includes known shipwrecks, archeological sites “anything that is culturally significant,” Landers said. “Also, we are taking into consideration the visual impacts to historic properties. So, there are national historic landmarks, lighthouses, historic districts along the coast that could be visually adversely impacted future offshore wind energy development.”

To give an idea of what the viewshed would be like, John McCarty, a landscape architect with BOEM, had designed simulations of what the viewshed would look like for wind turbines at different offshore distances. By illustrating the potential visual impacts, McCarty said it gives the public an opportunity to comment on what distance is acceptable for them from a visual standpoint.

Getting the power generated by wind turbines to the shore is another part of the puzzle, particularly what uses exist between a possible lease area and land.

BOEM Renewable Energy Program Specialist Josh Gange said the wind turbines produce energy that is then transferred to an offshore substation. The power is transmitted from there by an export cable buried under the sea floor to a point of interconnection onshore, which is typically another substation, and that’s where that power is then distributed throughout the existing grid.

BOEM economist Jayson Pollock said that overtime as technology evolves, there’s bigger output and more efficiencies are created but, like with anything, there’s tradeoffs. The further away from shore that a project is developed, the higher the cost will be and “I think that’s a very important point.” It costs more money for boats to go the distance, to manufacture longer cables, for example.

Vessel traffic is another conflict taken into consideration. BOEM oceanographer Will Waskes said that the Coast Guard is in the process of codifying fairways offshore for large ships, especially those traveling to and from ports. Once the fairways are formalized through the rulemaking process, the highways for ships will be considered conflicts for wind energy areas.

Jennifer Mundt, the assistant secretary for Clean Energy Economic Development under the North Carolina Department of Commerce, was on hand to answer questions from the state level.

Mundt amplified that the state is appreciative of the “collaborative spirit that BOEM brings” and the effort to solicit feedback from the public. “I think this is really important for a transparent process.”

In a follow-up call, Brian Walch with BOEM’s communication office told Coastal Review that the reception was positive from the 40 or so that attended. They seemed interested in the information and wanted to know more about the lease siting process.

It can take as long as a decade to develop a wind project from when there’s the first review of a possible lease area to when there could be any project actually in operation.

“BOEM is meticulous,” and thoroughly looks through the public comments, Walch said. Adding the team puts a great deal of effort in public outreach, like the open houses. There are four more for this round and “it’s a pretty significant undertaking” to get the staff and representatives in one place but BOEM feels that it is a responsibility to communities and to individuals.

Comments can be submitted until 11:59 p.m. Oct. 21 in writing by using the portal at regulations.gov or by mail to Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Office of Renewable Energy Programs, 45600 Woodland Road, Mailstop: VAM-OREP, Sterling, VA 20166.