Land once eyed for major development proposals on the riverfront across from downtown Wilmington should be conserved, New Hanover County commissioners agreed earlier this week.

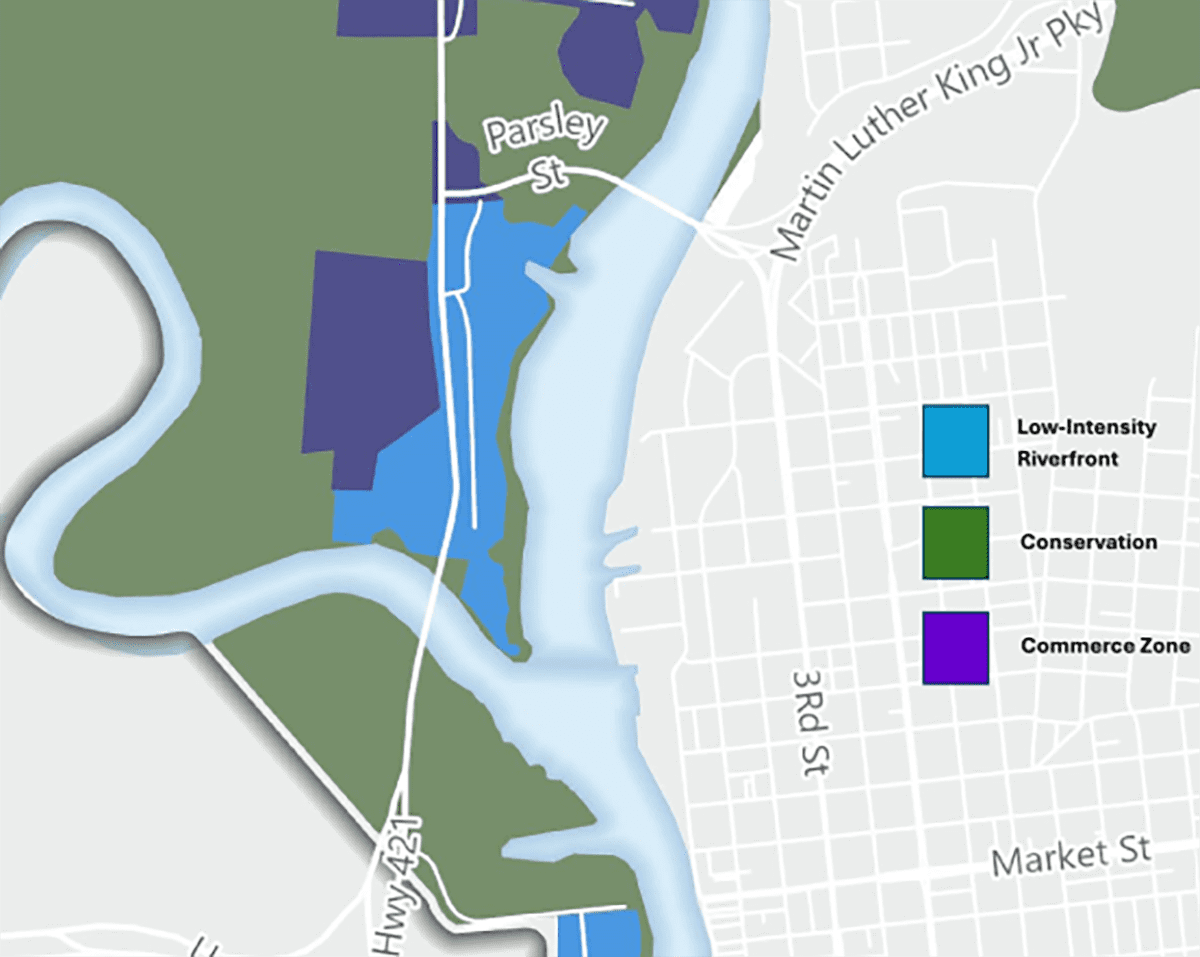

Following a public hearing Monday afternoon, the board approved a motion to continue the hearing and allow staff to draft a revised amendment to the county’s 2016 comprehensive land use plan to create a new conservation “placetype” specifically for the western bank at the confluence of the Cape Fear and Northeast Cape Fear rivers. “Placetype” is a planning term used to describe the mix of compatible uses within an area.

Supporter Spotlight

A conservation placetype is intended to protect significant natural areas by minimizing land disturbance.

The designation would articulate “our vision this area be conserved in its current state,” Commissioner Rob Zapple said as he made the motion, one that also includes adding a provision in the proposed revised amendment that the county will not agree to extend water and sewer utilities to the area.

Commissioners also agreed to direct county staff to search for state, federal and nonprofit funding and grants to help pay for the cleanup of brownfields and restore and preserve wetlands and estuaries on the western bank. That includes seeking out funding for the county to buy private properties along the river bank.

“What I’m in favor of is finding resources to purchase the property and compensate them justly,” Commissioner Jonathan Barfield Jr. said. “I’m hoping we can tap into some of the federal dollars that’s come down to our state and hopefully those property owners would be amenable to selling the property to the county and then, once we own it, then we could deem it as conservation land.”

Barfield was referring to the federal Climate Pollution Reduction Grants program, which is disbursing nearly $5 billion to states, local governments, tribes and territories to reduce carbon emissions and boost climate change resiliency efforts.

Supporter Spotlight

The Atlantic Conservation Coalition, which includes North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, Maryland and The Nature Conservancy, has been tapped to receive $421 million from the program to work in conjunction with nonprofit organizations for conservation and restoration projects.

The commissioners’ unanimous vote was met with applause from people who are among what has become an overwhelmingly unified force in opposition to development on the western bank, a movement that began a few years ago when the county was presented with development proposals for a riverfront multistory hotel and a pair of luxury condominium towers.

Opponents have raised a host of concerns about development on the river bank, where flooding is exacerbated by the rising sea, raising concerns about safety, potential economic impacts and the effects of stormwater runoff on surrounding properties, including the National Historic Landmark USS North Carolina.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, maps indicate that by 2050, between 75% and 80% of land along the western bank will be anywhere from 6 inches to several feet underwater, Zapple said.

“Everywhere you look on there in developing the western bank it is problematic and, in my opinion, it’s not a good idea,” he said.

Almost all of those who submitted the nearly 3,000 public comments to the county earlier this summer agreed.

New Hanover County Manager Chris Coudriet made clear that the commissioners’ decision on Monday does not change the current zoning of the land, which is I-2 Industrial District, one that allows minor industrial uses and uses on a more extensive scale. It does not allow residential development.

“And so, if a development were to proceed that is consistent with the existing zoning … those are projects that if they can meet the technical standards of the ordinance, in fact can go vertical,” he said. “So, this has been a discussion around what the vision should be, not exactly what the zoning on the ground is and so there is, by right, zoning, largely I-2, on that side of the river.”

Wilmington resident Logan Secord, the first of several who spoke at the public hearing, said the county cannot allow the current zoning to be reflected in the comprehensive land use plan.

“We must find a way to protect this land within the authority given to us since conservation, notwithstanding any resources available to us, to see what we can do to protect us,” he said. “We cannot have on the record messages to developers to say yeah, you can put a five-story building there that’s going to be underwater, you can build residences there, you can pay for the initial expansion of utilities and resources and then we foot the bill. This amendment to the comprehensive plan moves us in that direction. It is a step and one that should be of many.”

Isabelle Shepherd, representing the Historic Wilmington Foundation and speaking on behalf of a number of organizations, including Cape Fear River Watch, Alliance for Cape Fear Trees, League of Women Voters of the Lower Cape Fear, Cape Fear Historical Society, North Carolina Coastal Federation, which publishes Coastal Review, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or NAACP, said those groups agree all western bank parcels should be in the conservation placetype.

This “best preserves the historical integrity, cultural significance and natural environment of the area compared to creating a low intensity riverfront placetype as proposed,” she said.

Shepherd rattled off a list of considerations commissioners should take into account: Parcels on the western bank are part of a dynamic compound floodplain subjected to high tides, river flooding, and storm surge; the county’s unified development ordinance mandates development should not be risked in hazardous floodplains; development in flood-prone areas can lead to tax increases for county residents; developing the area would threaten historic and culturally significant lands; and that the land on the western bank is home to diverse ecosystems.

“The conservation development scenario would protect these critical habitats from the detrimental effects of urban development, such as pollution, habitat fragmentation and increased flooding,” she said. “Maintaining these natural assets ensures the sustainability of the local environment and its ability to provide essential ecological services. Our coalition understands the desire for development and that there are property rights concerns. We believe the hazardous condition of the area argues against the mixed use and low intensity development that are outlined as possibilities.”