Editor’s note: Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. More of his work can be found on his personal website.

I first learned about the Bohemian oyster shuckers who used to work in North Carolina’s oyster canneries almost 40 years ago.

Supporter Spotlight

I was living in Swan Quarter that winter, and I still remember how surprised I was when some of the old timers told me how, when they were young, Bohemian immigrants would come from Baltimore and work in a local cannery.

At the time, I wondered how they had come to be there, and what their lives had been like, and where else, besides Swan Quarter, they might have gone.

Many years have passed since those days in Swan Quarter, but I thought maybe it was time to see if I could discover their story.

Here is what I found out.

***

Supporter Spotlight

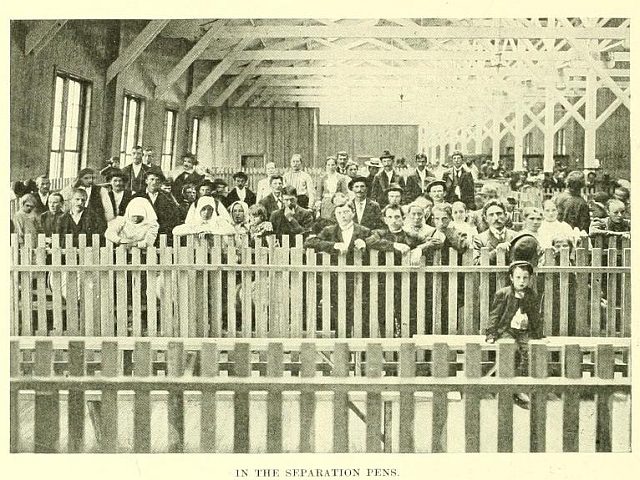

From 1890 until at least 1914, thousands of central and Eastern European immigrants worked in oyster canneries on the North Carolina coast. Typically recruited by “padrones,” or labor agents, in Baltimore, they all came to be known as “Bohemians,” though they had actually immigrated to the United States from many different parts of Europe.

They included men, women and children, all of whom, except for the youngest children, shucked and canned oysters. An unknown number of the men also worked on oyster boats.

Many had actually come from Bohemia, a land of low mountains and plateaus in what is now the Czech Republic. More, however, had left homes in other parts of Europe to come to America.

Among them were especially large numbers of Polish immigrants, but also Serbs, Dalmatians, and other Slavic peoples, Germans, and even Italians.

For simplicity’s sake, I will also refer to this diverse group of immigrants as “Bohemians,” unless historical sources allow me to identify their nation of origin more precisely.

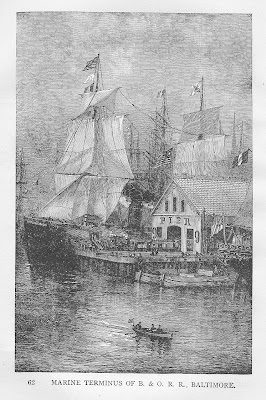

By the mid-19th century, Baltimore, Maryland, had become the center of the nation’s oyster industry.

But by the 1880s and 1890s, many of Baltimore’s oyster companies had begun to expand beyond Chesapeake Bay. They began to open canneries both on the North Carolina coast and as far south as Mississippi and Louisiana.

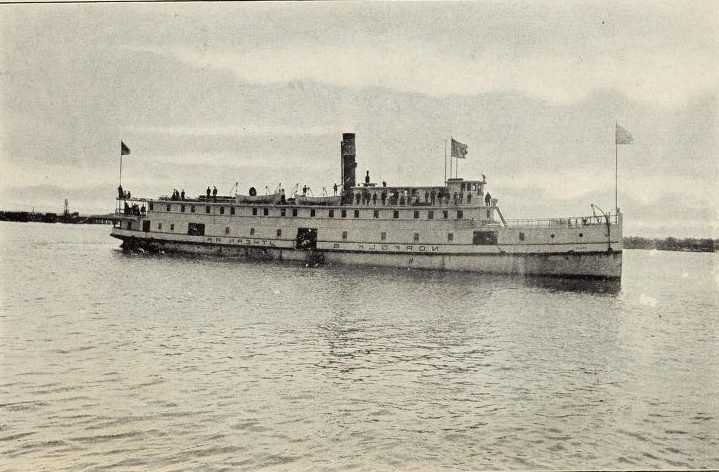

Many of those oyster canneries relied on immigrant laborers who had settled in Fells Point, Camden, and other waterfront neighborhoods in Baltimore, Maryland. Typically, they transported the Bohemian workers south by train, though some also traveled to the North Carolina coast by steamer.

For a time, the Bohemian immigrants seemed to be in every town and village on the North Carolina coast.

In my survey of coastal newspapers, I found the Bohemians working in oyster canneries in Elizabeth City, Swan Quarter, Belhaven, Washington, Morehead City, Beaufort, Marshallberg, Swansboro and Shallotte.

I suspect that the Bohemians worked in other oyster ports on the North Carolina coast as well, but sources are scant — I cannot be sure.

In some other parts of the coastal South, the Bohemians are at least somewhat better remembered. But, on the North Carolina coast, they seem to have been completely forgotten. To my knowledge, no book, article, or museum exhibit — or blog, podcast or anything else — has ever told their story.

Today I hope that I can take at least a small step toward changing that.

By drawing especially on coastal newspapers, and with help from some wonderful librarians, archivists, and museum curators, I will try to sketch the best portrait I can of the Bohemian oyster shuckers and their lives on the North Carolina coast between 1890 and 1914.

At the John Boyle & Co.’s Cannery at Goat Island

One of the best accounts that I found of the Bohemian oyster shuckers here on the North Carolina coast comes from Elizabeth City, a town on the Pasquotank River, just north of Albemarle Sound, that was transformed by the boom in the oyster industry that began in 1890.

In the spring of 1902, an Elizabeth City attorney and newspaper publisher named Walter L. Cohoon wrote an account of his visit to a large group of Bohemian immigrants that were living and working at the John Boyle & Co.’s oyster cannery on Goat Island.

John Boyle & Co. was one of probably half a dozen or more Baltimore companies that had opened oyster canneries in Elizabeth City since 1890. The company had first located in the town’s Riverside neighborhood, then moved to Goat Island, now called Machele Island, which is located just across the Pasquotank from Elizabeth City’s waterfront.

Cohoon and a friend or two crossed the river in a skiff, then tied up at the oyster cannery’s wharf on Goat Island.

Touring the cannery, they discovered a large force of Bohemian oyster shuckers, “four score of them,” as well as many local African Americans, hard at work.

At that time, the John Boyle & Co.’s workers could, at peak capacity, shuck and can 15,000 bushels of oysters a month, which amounted to some 16,000 cans of oysters a day.

In his newspaper, the Tar Heel, Cohoon wrote, “We listened to the songs of the negroes and to the broken English of the foreign element until becoming tired we turned our attention to the Bohemian quarters.”

They then walked next door to the barracks where the Bohemian workers and their families stayed during the oyster season.

“Here,” Cohoon reported, ” … we found one long room with rows of bunks built along the sides of the building.”

Seasonal and migrant labor camps of that kind were not uncommon on the North Carolina coast in that day, but Cohoon does not seem to have visited any of them before.

“The members of a dozen families lay themselves down to sleep with not so much as a thin curtain separating their different births. The sons and daughters of different families cooped up in one small building like so many beasts is a condition of affairs that one can hardly believe, yet such is a fact, and they live peacefully together, never trespassing or intruding upon one another in any other manner.”

‘Two Trainloads of Bohemian Goat Islanders’

The Bohemian oyster shuckers on Goat Island continued to show up in the pages of the Tar Heel for another couple of years.

The very next year, for instance, on April 10, 1903, the Tar Heel referred to the Bohemians while railing against a change in state law that regulated the oyster industry more closely.

In that article, the Tar Heel warned Elizabeth City’s citizens that the new law would have a disastrous impact on the town’s economy.

The headline read:

“The Oysterman’s Boats are Idle and without Employment. TWO BIG CANNERIES SUSPEND. Several Hundred Bohemians go Home—Colored Laborers are Walking the Streets—and the Oyster Tongers are out of Pocket Money.”

The Tar Heel observed that oyster cannery owners had gone to a great deal of trouble and expense to “send a mass of Bohemian population from Maryland to North Carolina.”

The newspaper then went on to say that local merchants would suffer if the Bohemian oyster shuckers left the North Carolina coast for good:

“In Elizabeth City alone, an entire island colony have migrated to Baltimore this week, whose combined salaries were practically invested here and who might have gone this month into the pockets of our merchants.”

The “entire island colony” was of course a reference to the Bohemian oyster shuckers at Goat Island.

The paper continued:

“The Boyle Oyster Canning Company suspended active business Wednesday the 1st. Monday April 6th two train loads of Bohemian Goat Islanders, left Elizabeth City for Baltimore, where they will engage in picking strawberries, or canning sundry goods.”

That was actually typical. When the oyster season ended on the North Carolina coast, usually later in April, the Bohemian immigrants most often returned to Baltimore to work either in canneries there or in the fields of Maryland and Delaware that supplied the city’s canneries with fruits and vegetables.

The Song of the Oyster Shucker

According to newspaper accounts, the first Bohemian immigrants had come to work in Elizabeth City’s oyster industry in the latter part of 1890.

In a December 1890 issue of another Elizabeth City newspaper, the Weekly Economist, I found an article that noted:

“The oyster packing house of Wm. Taylor received 75 Bohemian laborers yesterday from Baltimore with their families…. There are about 25 women and 15 to 20 children.”

At that time, oyster canneries and shucking houses were springing up along the North Carolina coast, but no place more so than in Elizabeth City.

Two years later, the Weekly Economist Oct. 27, 1893, looked back wistfully at the prosperity and excitement that came to Elizabeth City during that first year or two of the state’s oyster boom.

Pondering all of Elizabeth City’s history, the newspaper’s editor declared that he could only compare the impact of the oyster boom on the town to the days after the opening of the Dismal Swamp Canal in 1829.

Referring to the oyster boom, the newspaper observed:

“It was a jolly time—a new revelation. Population and money flowed in a perpetual stream and prosperity was felt in every fibre and pulsation of business.”

On one hand, he seemed anxious about the large influx of immigrants into what had been a relatively quiet southern town.

“New people, new faces, new ways, new manners, almost destroyed the homogeneity of the population,” he wrote.

On the other hand, the newspaper’s editor clearly found something intoxicating in that historical moment.

“The song of the oyster shucker was heard in the land, the refrain of its suggestive melody was joined by Bohemians, Hittites, Hivites, Jebezites, Virginians, Marylandros, and Afro-Americans, in happy harmony and peaceful intercourse.”

“Every Saturday night was a new and upward departure in business,” he exclaimed. “There was money and plenty of it in all hands.”

While the local oyster industry never again reached the heights it did in 1890-91, Elizabeth City remained home to oyster canneries well into the first decade of the 20th century, and Bohemian immigrants continued to make the journey from Baltimore to work in the town’s canneries.

The John Boyle & Co. cannery continued to employ Bohemian oyster shuckers at least until 1903. According to the Virginian-Pilot in Norfolk, Virginia, “Bell’s oyster house” in Elizabeth City also employed “a large force of Bohemian oyster workers” in those first years of the 20th century.

Other oyster canneries in Elizabeth City likely employed Bohemian immigrants as well, but I have not found any record of them doing so.

Beaufort, Morehead City and Marshallberg

Another part of the North Carolina coast where “the song of the oyster shucker” could be heard was Beaufort, a small town in Carteret County where local people had always made their livings from the sea.

I found historical references to Bohemians working in Beaufort’s oyster canneries from 1890 to 1914.

In December 1890, for example, The Daily Journal in New Bern reported that a sizable group of Bohemian immigrants had passed through that coastal town on their way to a cannery in Beaufort.

A few weeks later, a second group passed through New Bern. According to The Daily Journal Jan. 15, 1891, they arrived on the steamer, Neuse, then took a train east to Morehead City, where they could board a ferry for Beaufort.

Surveying the Bohemians passing through New Bern, The Daily Journal’s correspondent wrote:

“There were in all about 100 people, about 75 of whom were workers, the remaining 25 being children too small for labor. They were especially Poles and Bohemians, but there were a few Germans among the number. They appear to be quiet, industrious people, who will make desirable citizens.”

Over the years, large numbers of Bohemian shuckers worked in oyster canneries both in Beaufort and in other parts of Carteret County.

For instance, a report in Washington Progress, Feb. 2, 1892, indicated that the North Carolina Packing Co. was employing Bohemians at its oyster cannery in Beaufort.

Six years later, The Daily Journal in New Bern on Dec. 15, 1898, reported that Bohemian oyster shuckers were working at the A.B. Riggin & Co.’s oyster cannery in Marshallberg, a village 8 miles east of Beaufort.

“The steamer Neuse brought in quite a passenger list yesterday, the large number being Bohemians of all ages, from infants in arms to grandmothers. The crowd were from Baltimore…. [and] were engaged by the Oyster Canning Factory at Marshalberg, and will shuck oysters at the factory. There were 48 persons in the party.”

That same month, a Raleigh newspaper, Carolinian, reported Dec. 22, 1898 that “fifty foreigners” were shucking oysters at the Booth Packing Company’s cannery in Morehead City.

Two years later, on Oct. 30, 1900, the New Berne Weekly Journal commented that “about 20 Bohemians” had passed through New Bern on their way to an oyster cannery in Beaufort.

“They came from Baltimore and were men, women, and children,” the newspaper observed.

![Surveying the Bohemians passing through New Bern, The Daily Journal’s correspondent wrote: “There were in all about 100 people, about 75 of whom were workers, the remaining 25 being children too small for labor. They were especially Poles and Bohemians, but there were a few Germans among the number. They appear to be quiet, industrious people, who will make desirable citizens.” Over the years, large numbers of Bohemian shuckers worked in oyster canneries both in Beaufort and in other parts of Carteret County. In 1892, for instance, a newspaper report indicated that the North Carolina Packing Company was employing Bohemians at its oyster cannery in Beaufort. (Washington Progress, 2 Feb. 1892) Six years later, The Daily Journal in New Bern (15 Dec. 1898) reported that Bohemian oyster shuckers were working at the A. B. Riggin & Co.’s oyster cannery in Marshallberg, a village eight miles east of Beaufort. “The steamer Neuse brought in quite a passenger list yesterday, the large number being Bohemians of all ages, from infants in arms to grandmothers. The crowd were from Baltimore…. [and] were engaged by the Oyster Canning Factory at Marshalberg, and will shuck oysters at the factory. There were 48 persons in the party.” That same month, a Raleigh newspaper reported that “fifty foreigners” were shucking oysters at the Booth Packing Company’s cannery in Morehead City. (Carolinian, 22 Dec. 1898) Two years later, on October 30, 1900, the New Berne Weekly Journal commented that “about 20 Bohemians” had passed through New Bern on their way to an oyster cannery in Beaufort. “They came from Baltimore and were men, women, and children,” the newspaper observed.](https://coastalreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/headline.webp)

Polish Oyster Workers in Swansboro

At least for a time, in 1907 and 1908, Bohemian oyster shuckers were also working and living in Swansboro, an old seaport that is in Onslow County, just across the White Oak River from Carteret County.

In Swansboro, the immigrant laborers worked at a cannery owned by a local merchant named Guy D. Potter.

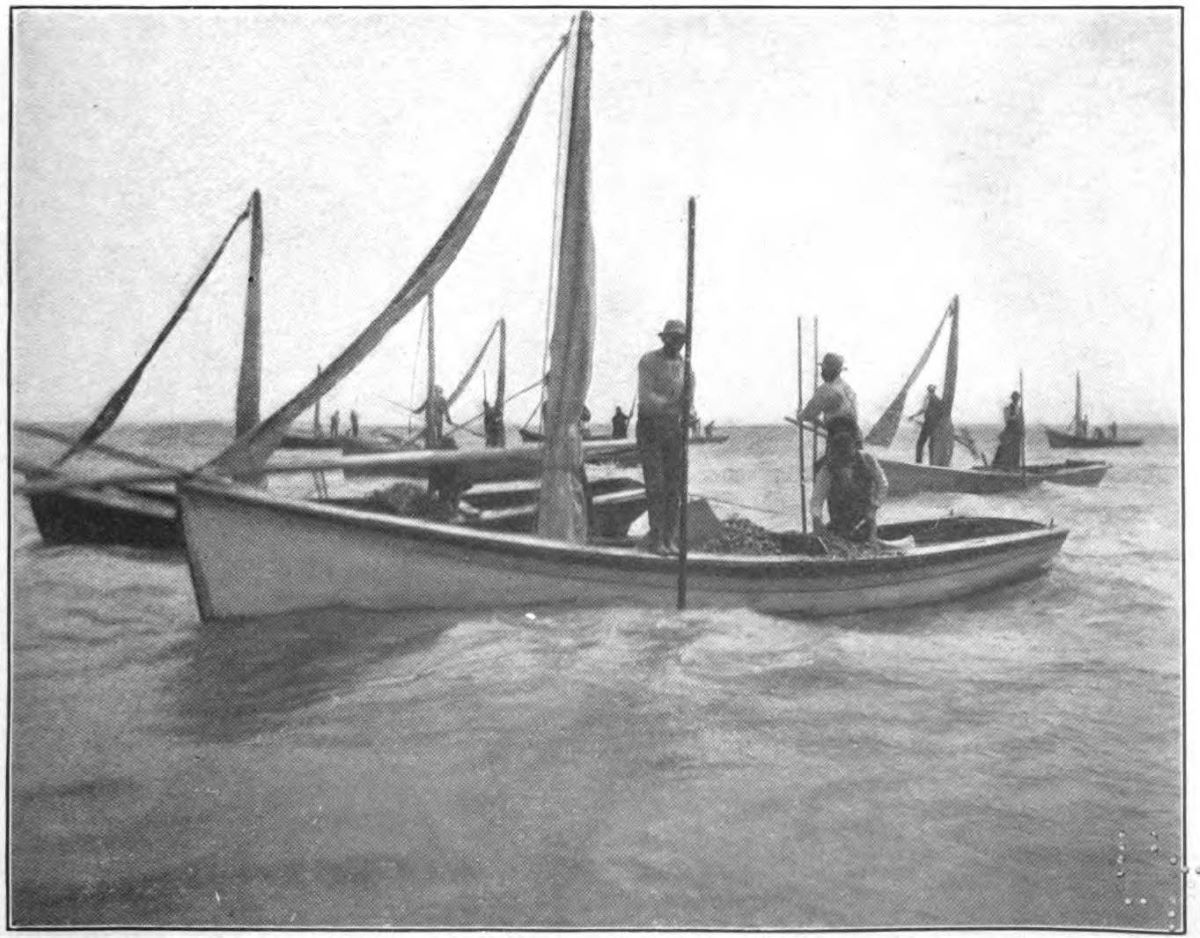

On Oct. 11, 1907, New Bern’s Daily Journal reported that Potter had gone to Baltimore to recruit “a hundred head of Poles as shuckers.”

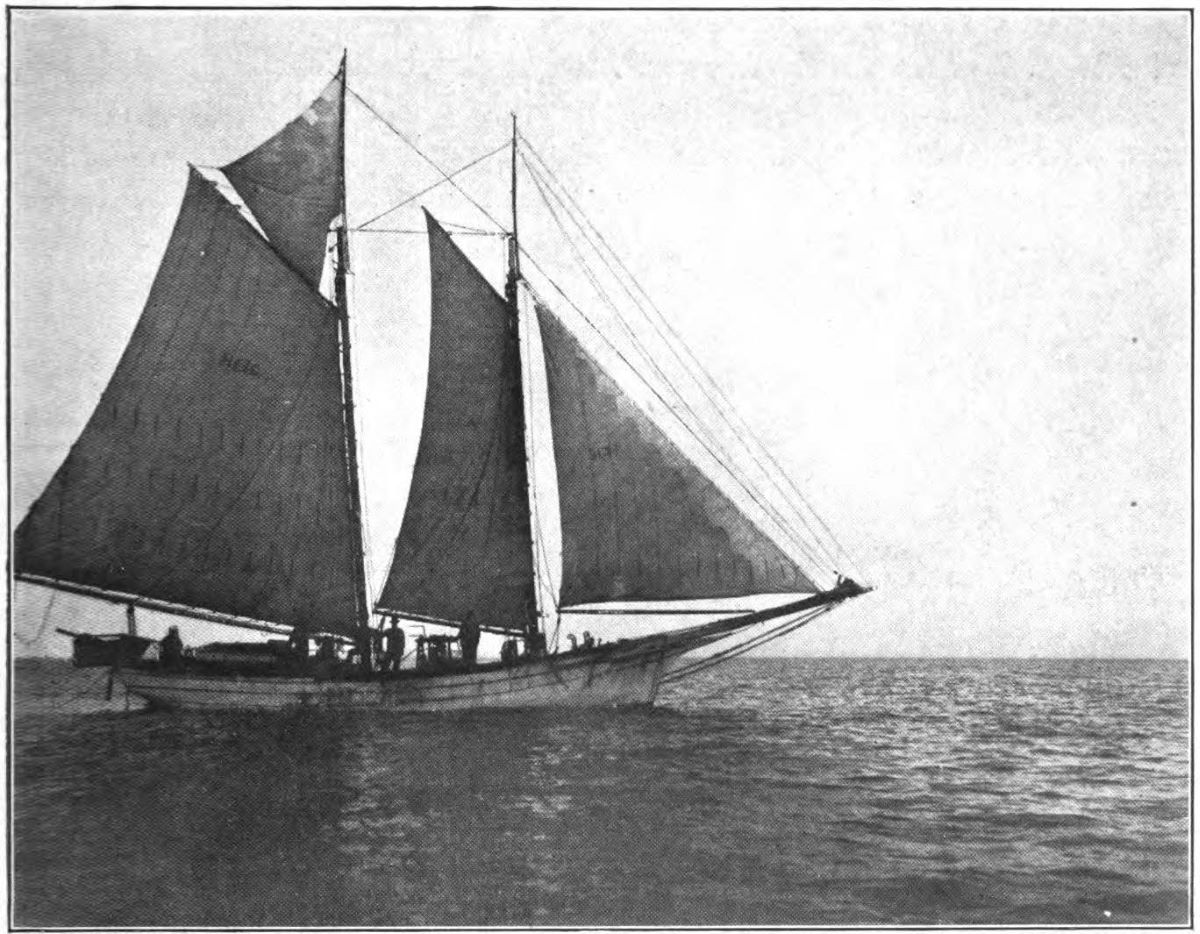

Six months later, on March 31, 1908, an article in the New Bern Weekly Journal indicated that Potter employed the Poles not only to shuck oysters, but also to harvest the oysters.

We only know that was the case, unfortunately, because the newspaper reported that one of the Polish immigrants had a tragic accident while returning from the oystering grounds. According to the Weekly Journal, his sail skiff overturned and, unable to swim, he drowned.

The report did not give the Polish oysterman’s name. It did however say that he left a wife and four children in Swansboro.

At Thomas Duncan’s Cannery in Beaufort

The last reference that I found to Bohemian oyster shuckers in Carteret County was in the April 4, 1914, edition of the New Bern Sun Journal.

That article was brief. It indicated only that a Beaufort oyster cannery owner named Thomas Duncan had accompanied a large group of Bohemian immigrants back to Baltimore.

The Bohemians had worked for him that winter and were returning to Baltimore after finishing the oyster season in Beaufort.

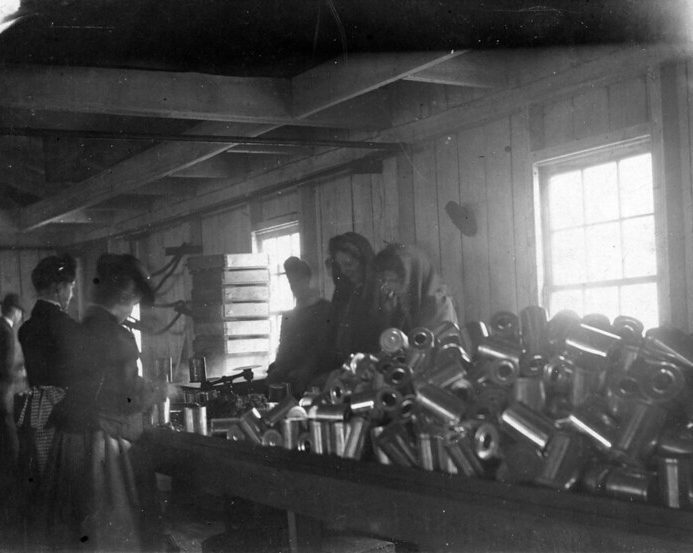

The article gave no more details. However, I found it especially interesting because several photographs at the State Archives of North Carolina show interior scenes of Thomas Duncan’s oyster cannery in Beaufort.

One of those photographs, above, shows a group of women wearing dark hats and shawls in the oyster factory’s canning room.

Another photograph, at the top of the post, shows a long view of the cannery’s shucking room.

I cannot say for sure, but I strongly suspect that at least the first photograph, and probably the second, portray Bohemian immigrants, as well as, in the case of the second photograph, African Americans.

If that is correct, they may be our only surviving images of Bohemian oyster shuckers anywhere on the North Carolina coast.

‘Bohemian Headquarters’

Another, very different account of the Bohemian oyster shuckers on the North Carolina coast, comes from the Washington Gazette, a newspaper published in Washington.

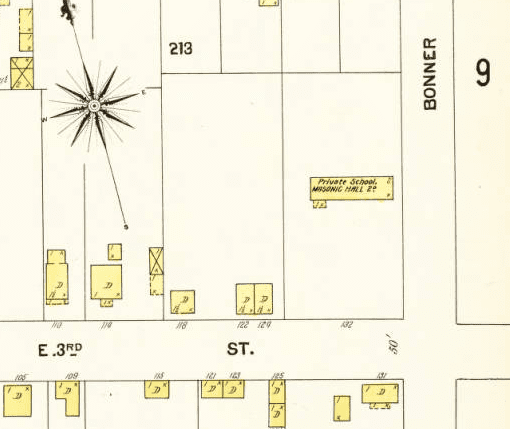

On Nov. 6, 1890, at the height of the oyster boom, one of the Gazette’s writers described his visit to what he called Washington’s “Bohemian Headquarters.”

He was referring to an old school building on Third Street that had been converted into a migrant labor camp for the oyster season.

I do not know what the Gazette’s reporter expected to find at “Bohemian Headquarters.” Evidently it was not this:

“It was discovered that a fiddle and a banjo were employed in dispensing sweet music, while about two dozen gushing Bohemian maidens with pale-faced partners were tripping the regular old fandango in high glee.”

He must have gone there on a Saturday evening, after the oyster shuckers finished their shift at a local cannery.

The Gazette’s correspondent apparently enjoyed his visit. He observed that “both men and women seemed courteous and kind.”

He also mentioned in passing that he found some of the young women quite attractive, and he expressed some surprise at how many of the Bohemians were “conversing well in English.”

He then went on to describe their living quarters:

“There are 63 quartered in the building which crowds it to its uttermost capacity…. The only furniture noticed were trunks or chests with one or two bedsteads. The balance of the sleeping paraphernalia consists of bunks in a continuous row from one end of the room to the other. There were four or five stoves placed about the room….”

Most likely, that group of Bohemian immigrants was employed at the J.S. Farren & Co.’s oyster cannery that was located on the town’s waterfront, near what is now the Children’s Park.

Based in Baltimore, J.S. Farren & Co. had opened the cannery earlier that fall.

Another Baltimore firm, the H.J. McGrath Canning Co., also opened an oyster cannery in Washington that winter. However, its workers had not yet arrived from Baltimore at the time that the Gazette’s correspondent wrote his story.

According to another local newspaper, the Washington Progress on Jan. 13, 1891, 100 Bohemian oyster shuckers arrived in Washington a week or two after New Year’s to begin work at the McGrath cannery.

I do not know how many more years the Bohemians came to Washington. The last reference that I found to them in the town’s oyster industry was from the Washington Gazette on Feb 18, 1892.

Anti-immigrant Views

When he visited the “Bohemian Headquarters,” the Washington Gazette’s correspondent seemed to have been rather charmed by the oyster shuckers from Baltimore.

However, I found a much different sentiment expressed in the Gazette the next year.

At that time, an uncredited article on the Gazette’s front page had this to say about the Bohemian immigrants:

“The Bohemians are rapidly developing the innate cussedness of their true nature. They are a nuisance in the sections where they are located and the sooner Washington is rid of this very undesirable acquisition to her population the better pleased many of her citizens will be.”

Where that hostility was born, and why the Gazette’s view of the Bohemian oyster shuckers had changed so profoundly, is far from clear.

Had some incident occurred that colored town leaders’ attitudes toward the immigrants?

Or perhaps that comment reflected anti-immigrant or even anti-Catholic bias, both of which were on the rise in the U.S. at that time? Most of the Bohemians came from predominantly Catholic homelands.

Or had cannery owners courted trouble by employing immigrant laborers instead of hiring local workers?

Those are all possibilities, but I do not have anywhere near enough evidence to say more.

‘Now she now sleeps in quietude’

In that same year, 70 miles away, an even darker view of Washington’s Bohemian immigrants was expressed in the Perquimans Record, a newspaper published in the coastal town of Hertford.

On March 18, 1891, the Record noted that a train carrying Washington’s Bohemian shuckers back to Baltimore at the end of the oyster season had passed through Hertford.

Referring to Washington, the newspaper’s correspondent wrote, “Our sister town has at last gotten clear of the dirty, ugly tribe, and now she sleeps in quietude.”

I do not know what stirred the Perquimans Record to that level of maliciousness, but clearly some local people greeted the Bohemian oyster shuckers warmly and others did not.

At the Pungo River and Swan Quarter

Bohemian immigrants also worked in oyster canneries in the more remote coastal communities east of Washington.

On Oct. 23, 1903, for instance, the Elizabeth City Tar Heel reported that “two (train) carloads of Bohemians” were en route to Belhaven, 25 miles east of Washington.

Beginning in the late 19th century, hundreds of oyster shuckers — one government report said as many as a thousand — left their usual homes and created what amounted to a here-today, gone-tomorrow boom town of oystering people there on the banks of the Pungo River.

Another 25 miles east, Bohemians were also shucking oysters in Swan Quarter, a village bordered by seemingly endless plains of salt marsh on the edge of the Pamlico Sound.

I lived in Swan Quarter for a time when I was young, and I remember old-timers then telling stories about the Bohemian immigrants who used to come and shuck oysters there.

However, the only newspaper account I found that mentioned those immigrant laborers concerned a brawl that broke out between them and local oystermen in February 1902.

That story ran in several North Carolina newspapers, including the Kinston Free Press of Feb. 11, 1902:

“Some Bohemians, who are employed at the oyster canneries there, were having a dance, when the crews of several [oyster] dredges came ashore and attempted to take charge of the dance.”

The story continued:

“A general fight ensued, and when the smoke of the battle cleared away it was found that 13 people were wounded, seven of them seriously, four badly cut and three shot.”

Whether that incident was rooted in tensions between locals and immigrants or was just a run-of-the-mill dance hall fight — fights were almost a Saturday night ritual in some coastal villages — I do not know.

All I can say for sure is that if the fight had not made the news, I would not have found any written evidence of Bohemian oyster shuckers ever living and working in Swan Quarter.

By the Calabash River

The last incident involving Bohemian oyster shuckers that I want to mention comes from the quiet salt marsh creeks located below Shallotte, 50 miles southwest of Wilmington.

The exact location of the oyster cannery where the Bohemians worked there is somewhat uncertain, but as best I can tell it was 12 or 13 miles below Shallotte, in the vicinity of the Calabash River.

According to several articles that ran in the Wilmington Morning Star in December 1907, 60 Bohemians — actually Poles, by all accounts — were recruited in Baltimore and transported to the A. B. Riggin & Co.’s oyster cannery on that part of the North Carolina coast. Copies of the articles are in the Brunswick County Historical Society’s newsletter of April 2007.

Things must have been bad at the cannery. Only a few days after arriving there, half of the Polish workers gathered whatever possessions they had and left. According to a Dec. 1, 1907, account, they had found “the pay and conditions” at A.B. Riggin & Co. intolerable.

They did not have an easy time getting back to Baltimore. Some walked all the way to Wilmington. Others somehow got passage to Wilmington aboard a steamer called the Atlantic.

According to the Wilmington Morning Star, the Poles spoke little or no English, and they seem to have been penniless. When they reached Wilmington, they had no place to stay, so town leaders let them bed down for a few nights first at the police station, then at City Hall.

Many stayed in Wilmington for a time and took temporary jobs at a local lumber mill. Others did farm work. A few chopped wood and did other odd jobs around the seaport.

As best I can tell, they probably worked just long enough to earn passage home to Baltimore.

Four or five other Poles got home by taking passage aboard “the leaking schooner Grace Seymour in exchange for manning the pumps on the voyage North,” a grueling job if ever there was one.

Remembering the Bohemian oyster shuckers

The history of these Bohemians immigrants — these Czechs, these Poles, these Slavs, Italians and others — is remembered at least somewhat better in other parts of the American South.

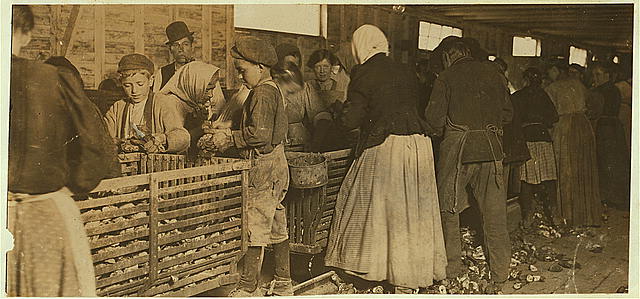

To an important degree, that is because of a child labor investigation more than a century ago.

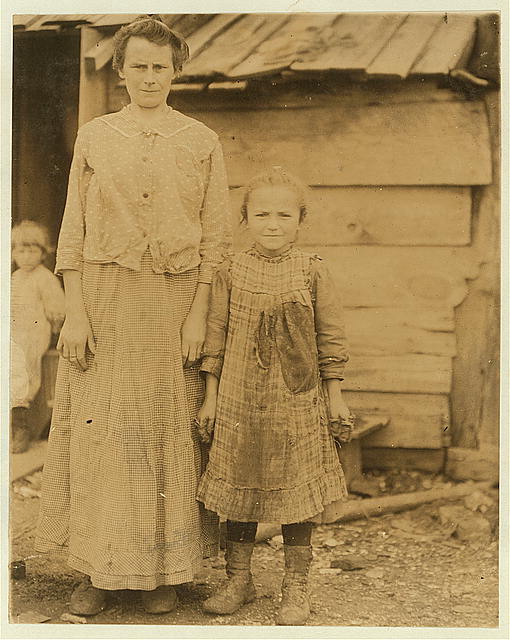

Between 1909 and 1916, a social reformer named Lewis Hine documented “Bohemian” and local children, both Black and white, in oyster and shrimp canneries in Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, Florida and South Carolina.

Working for the National Child Labor Committee, Hine used his photographs and reports to advocate for stricter child labor laws across the U.S.

His photographs are powerful, and many, particularly those of the youngest workers, are unforgettable. They stunned many people when they first appeared in newspapers, magazines, and books.

Now preserved at the Library of Congress, Hine’s photographs and investigative reports highlighted child labor in the South’s oyster industry.

But they also brought public attention to the low wages, long hours, and often atrocious working conditions that shuckers of all ages, races, and backgrounds experienced in oyster factories at that time.

In the parts of the coastal South that he visited, Hine’s work assured that the Bohemian oyster shuckers, and really all who worked in oyster canneries, would be remembered.

Lewis Hine never visited the North Carolina coast, however.

Without his work to remind us of them, all memory of the Bohemian oyster shuckers — and really all those who worked in North Carolina’s oyster canneries — gradually faded away here, then was lost.

What I hope is that what I have written here today, however incomplete it is, might be the beginning of remembering them.

* * *

For their help with the research for this story, I want to express my deep gratitude to Stephen Farrell at the George H. and Laura E. Brown Library in Washington, N.C.; Ray Midgett of the Historic Port of Washington Project; David Bennett at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort (especially for his work on A.B. Riggin & Co.); and to my old friend Amelia Dees-Killette at the Swansboro Area Heritage Center Museum.

I also want to extend a special shoutout to my dear friend Bland Simpson for his lyrical evocation of Machele Island in “The Inner Islands: A Carolinian’s Sound Country Chronicle,” one of my favorite books.

If you want to learn more about the history of the state’s oyster industry, my essay “The Oyster Shucker’s Song.” might be helpful. And if you’d like to read more about the Bohemian immigrants in the South as a whole, I wrote a piece called “Shuckers and Peelers” for Southern Exposure magazine many years ago that you might find interesting.

I dedicate this story to the memory of one of my ancestors on the Polish side of my family, my great-uncle Peter, a lobsterman who lost his life at sea.