The coastal historian Jack Dudley recently gave me copies of some wonderful historical photographs of Mashoes, a fishing village now almost gone, that sits on a remote and solitary hammock on the mainland of Dare County, just northwest of Roanoke Island.

For me they brought back memories. I first visited Mashoes 40 years ago, during a winter when I was living on the shores of Lake Mattamuskeet, on that same part of the North Carolina coast.

Supporter Spotlight

Even then, the Mashoes I saw was almost a ghost town. The fish houses had been abandoned. The old church was gone. The boatyards had grown quiet.

But there were still a few cottages there, and a few signs of life, including a gill net drying in a fisherman’s backyard, several garden plots, and two or three boats tied up at the docks.

Above all, I remember how beautiful Mashoes was, and its solitude, and how frail the little village looked, surrounded by broad waters and miles of salt marsh and pocosin thicket.

I wondered then what its story was. I longed to know how Mashoes had come to be there, and if it had ever had more life to it, and who had lived there, and what their lives been like.

When Jack showed me the photographs, my memories of that day all came back. And at that moment, I decided that I would try to see if I could learn more about Mashoes’ past.

Supporter Spotlight

–2–

As I looked into the history of Mashoes (pronounced “Mee-shoes”), I quickly discovered that there had been settlers on that remote point of land by the time of the Revolutionary War, if not before.

For instance, according to the Native Heritage Project, a genealogical effort to document Native Americans, a mariner named John Payne purchased 160 acres at Mashoes Creek in 1773.

By 1786, Payne was living there with his family and was holding 13 African Americans in slavery, most of whom, I assume, would have forced to labor as fishermen or in other maritime trades.

Land, tax, and census records gave me some sense of settlement along Mashoes Creek in the 1700s and 1800s, but I discovered that I could not really find descriptive portraits of Mashoes until the 20th century.

Between 1930 and 1940, in particular, a flurry of newspaper accounts described visits to Mashoes. That sudden interest in the little village, I soon learned, was due to a local fisherman and storekeeper named Thomas Loyal Midgett, who in those years undertook what was largely a one-man campaign to persuade the state to build the first road to Mashoes.

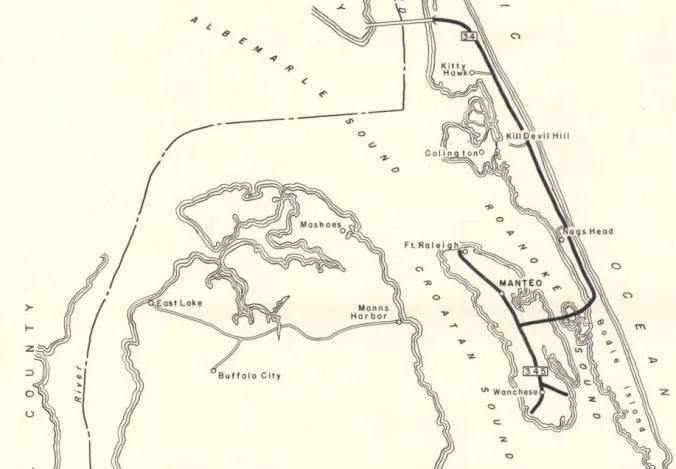

Up to that time, Mashoes might as well have been an island. The waters of Albemarle Sound, Croatan Sound, and East Lake wrapped around the village, except to the south, where swamplands and salt marshes separated the village from the rest of mainland Dare County.

No road had ever crossed that swamp and marsh. All travel and trade to and from Mashoes had always been by boat.

Historically that had not been unusual on the mainland of Dare County. For instance, Stumpy Point, a fishing village 20 miles south of Mashoes, was at least as isolated as Mashoes until 1926, when the state completed a road that ran from Stumpy Point to Engelhard.

But by the 1930s, Mashoes was an outlier. By most accounts, Mashoes was the last village anywhere on the mainland of the North Carolina coast that was not accessible to automobiles.

Beginning about 1930, Thomas Loyal Midgett, Capt. Tom, most people called him, set out to change that. He traveled to Manteo, the county seat, and perhaps to Raleigh as well, to convince public officials to build a road to Mashoes.

He also began inviting newspaper reporters to Mashoes to build public support for the construction of a road.

Midgett was kind of Mashoes’ unofficial mayor, and he had been watching the village’s population decline sharply during the early years of the Great Depression.

Nearly all the village’s people were fishermen and their families. Yet during the Depression years, very few fishermen anywhere on the North Carolina coast could make a decent living — the number of commercial fishermen on public relief was staggering.

The Great Depression strangled fishing communities across the Outer Banks and along North Carolina’s sounds and bays.

With so many people unemployed, and with wages and farm prices plummeting, fewer Americans were buying fresh fish. At times, the state’s fishermen left fish to rot on the beach because seafood dealers could not find a market for them.

Some fishing communities proved more vulnerable to the economic downturn than others, however. The fate of any fishing village without a road — or without a railroad to northern markets, or a bridge to the mainland, if it was on an island — hung by a thread. Many of those communities did not survive the Great Depression.

Seeing what was happening, Tom Midgett hoped that a road across the swamplands would bring new life to Mashoes.

Fortunately for those of us interested in North Carolina’s coastal history, several journalists who were Capt. Midgett’s guests in Mashoes later published newspaper stories about the village, including what some of the old timers there told them about its history.

With the help of other sources in the collections of the Outer Banks History Center and the State Archives, those newspaper stories gave me at least a glimpse of what the village was like both in the 1930s and in earlier times, before anyone had ever dreamed of a road.

–3–

One of the most interesting newspaper articles on Mashoes was published in the Raleigh News & Observer on Nov. 27, 1938.

The author of the article was Ben Dixon MacNeill, a journalist who later wrote a well-known account of the Outer Banks called The Hatterasman and a novel, published posthumously, called Sand Roots.

In his N&O story, MacNeill described how he began his journey to Mashoes at Roanoke Island, where at that time he was the publicist for Paul Green’s new outdoor drama “The Lost Colony.”

A bridge had not yet been built between Roanoke Island and the mainland of Dare County, so he took a private ferry across Croatan Sound to Manns Harbor, a fishing village seven miles south of Mashoes. He then found a fisherman to take him up the coast to Mashoes.

In Mashoes, MacNeill found perhaps a dozen families living along what locals called “Peter Mashoes Creek.” (More on that name later.) A little arc of old fish houses stood on wood pilings around the village’s harbor. There was a church, a school, a post office, two abandoned stores.

He described seeing sheep grazing on the grassy cart road that ran from the docks up into the little settlement.

One of the first places that he visited was the village school, said to be the smallest in the state. The teacher, Carrie Mae Lowe, greeted him there. She had come to Mashoes from Rockingham, N.C., 250 miles away, to take the teaching job. She must have had an adventuresome spirit.

Ms. Lowe taught only seven students, though, she said, it was eight if you included Briary, sixth grader Boyd Basnight’s dog. She told Ben Dixon MacNeill that Briary accompanied Boyd to school every day.

“Now that she is used to local custom, [Miss Lowe] would never think of omitting Briary when she calls the roll,” MacNeill wrote. “He is now a member of the 6th grade … and has a desk all to himself. He sits there and behaves himself. … Miss Lowe says he is a very smart pupil.”

While he was in Mashoes, MacNeill watched three young children arrive at the school by boat. Six-year-old Wilton Westcott was behind the oars, his two sisters enjoying the ride.

Ms. Lowe explained that the children lived on an isolated rise a mile down the creek and always came to school that way.

–4–

A personal story: my mother’s fourth grade teacher in Beaufort, N.C., was evidently cut from the same cloth as Ms. Lowe. A year before Ben Dixon MacNeill found Boyd Basnight’s puppy attending school in Mashoes, my mother’s German shepherd Mike-Dog was going to school with her.

My mother’s father David had died in a terrible accident in the fall of 1937. After his death, my mother’s teacher allowed my grandmother to send my mother to school with Mike-Dog.

Mike-Dog rested by my mother’s desk for the rest of that school year and was, my mother later told me, a tremendous comfort to a heartbroken little girl. And like Briary in Mashoes, he was, she said, always well behaved.

–5–

Huts of Rough Boards

In the April 4th, 1930, edition of The Independent, a newspaper published in Elizabeth City, journalist Victor Meekins described a recent visit to Mashoes:

“Down on the creek about 150 yards from the Midgett store and home, is a scene of much activity these days. A hundred shad fishermen live in huts of rough boards … and make this their rendezvous for the season.”

He continued, “They get out at daylight, to their nets anchored, or tied to stakes in the rough waters of Albemarle Sound.”

–6–

On the day that he visited Mashoes, Ben Dixon MacNeill also visited the home and boatyard of William “Bill” Howett. Born nearby in 1864, Howett was just shy of 75 at that time, but he had been one of the foremost builders of traditional workboats on that part of the North Carolina coast for many years.

Howett was one of two master boatbuilders in Mashoes that built the elegant, sweet sailing wooden workboats known as “shad boats” in the late 19th and early 20th century.

“He remains the premier boat builder of that country,” Ben Dixon MacNeill wrote his News & Observer article in 1938.

The other shad boat builder in Mashoes was Ken Mann, who apparently had a boatyard in the village for a time, but at another time had his boatyard on Rabbit Island, a marshy rise just off Mashoes that has washed away in the years since that time.

For more on shad boats and shad boat builders, see my 12-part series “The Story of Shad Boats.”

That series features the research of the two most knowledgeable authorities I have ever known on the history of these distinctive traditional workboats– Mike Alford, the former curator of traditional workboats at the N.C. Maritime Museum in Beaufort, and Earl Willis, a now retired schoolteacher who grew up among the last generation of shad boat builders in Wanchese, N.C.

When Howett passed away a few years later, his obituary in the Dare County Times (Dec. 11, 1942) noted that fishermen had long come to Mashoes from great distances to have him build a boat built for them.

To some he seemed something of an eccentric, but I always take that kind of reputation with a grain of salt. In my experience, it often meant that an individual retained the values and outlook of an earlier age, and perhaps failed to embrace other people’s notions of progress and a modern life.

“For many, many years,” MacNeill wrote, “people have been going to Mashoes to get their boats built by this old man, nobody knows how old he is. When they look at the tools with which he does his work, they doubt that anyone could build a raft with them, but when they see the product finished in marvelous strength and smartness and beauty, they marvel at the genius and patience of the man.”

–7–

“To Get Away from the World”

On Nov. 19, 1939, a reporter from another newspaper, The News & Record, of Greensboro, N.C., also spoke with Peter Howett on a visit to Mashoes. In the interview, Howett told him he remembered when fishing boats from all over Dare County crowded the village’s little harbor.

“Why, I mind the time when more than 200 boats were tied up there at one time—and it was me that built most of them.”

Howett went on to say:

“They came from Manns Harbor and from Stumpy Point and from Roanoke Island and pitched their tents or built makeshift shacks down there by the beach during the fishing season. I was right there with them, too.”

According to the reporter, Howett’s elders had told him when he was young that Mashoes had originally been just a fish camp.

He meant the kind of place where people didn’t usually live, but where fishermen gathered only for the fishing season, lived rudely, cooking over fires, and no doubt sharing story, song, and more than a little bit of East Lake liquor, then went home.

Howett said that changed after the Civil War. “With the coming of peace,” the News & Record’s correspondent was told, “many of the men who had suffered during the war felt the need to get away from the world so a number of houses sprang up in Mashoes during the next few years.”

That image of Mashoes in that day stayed with me: a village built as a refuge for broken men and those weary of war and killing.

–8–

While in Mashoes in 1938, Ben Dixon MacNeill observed that an old wooden boat called the Hattie Creef bound the village to Elizabeth City and to other isolated fishing villages on that part of the North Carolina coast.

The Hattie Creef was a 55-foot-long vessel owned by the Globe Fish Company, a wholesale seafood dealer that two brothers in Wanchese, Ezekiel R. and Arthur S. Daniels, had founded in 1911.

George Washington Creef, who is best known for inventing the shad boat, built the Hattie Creef at his Manteo boatyard in or about 1888. He built her for oystering, but the Daniels turned her into a buy-boat sometime between 1911 and 1915.

In the late 1930s, when MacNeill was in Mashoes, the Hattie Creef arrived at the village’s docks every day during the fishing season. The boat’s hands unloaded ice for the next day’s catch, and they picked up that day’s catch, which would ultimately end up in Elizabeth City.

That was the site of the nearest railroad to Mashoes and to a host of other remote fishing villages on that part of the North Carolina coast. In Elizabeth City, the fish were loaded onto refrigerated cars and sent to Norfolk, Baltimore, and other markets to the north.

At that time, the fishing business in Mashoes could not have survived without the Hattie Creef. However, the old boat was important to the villagers in other ways, too. Most importantly, its captain was always happy to give a lift to local people bound anywhere on his route.

As a result, the Hattie Creek helped connect Mashoes to the rest of the world. From Mashoes, the village’s residents could take the Hattie Creef to buy provisions in Elizabeth City, to see a doctor in Manteo, or to visit a sister or a girlfriend in some of the other fishing villages that were on the boat’s regular run, such as Manns Harbor and Stumpy Point.

–9–

On March 27, 1896, The Weekly Economist in Elizabeth City reported that a large crowd of some 100 fishermen had moved into camps in Mashoes for the shad fishing season.

That same issue of The Weekly Economist noted that the “Davis’ seine fishery” in Mashoes was also busy.

That may be a reference to the Croatan Fishery, a massive undertaking that had been operating on the upper part of Croatan Sound since at least the early 1800s.

Owned by Col. William “Bill” Davis of Elizabeth City for much of the late 19th century, the fishery was manned by large gangs of African American fishermen who harvested the fish in a heavy rope seine that was more than a mile long.

The size of their catches was mind boggling. The largest record of a catch at the Croatan Fishery that I found was a single haul of at least 450,000 fish, requiring two days of labor.

Several other historical accounts refer to that kind of seine fishery operating at Mashoes in the 19th century. However, I cannot be sure that the Croatan Fishery and the “Davis’ seine fishery” were one and the same. Another seine fishery may also have operated in the vicinity of Mashoes in 1896.

One possibility, which I can’t rule out, but have no evidence for, is that Isaac N. Davis, a merchant in Wanchese, was behind the “Davis’ seine fishery.” Davis had been in the shad fishing business since the 1870s, and he may have had the financial wherewith necessary for a smaller, less capital intensive seine fishery.,

Either way, “the Davis’ seine fishery”— and its large number of presumably African American fishermen— was yet another contributor to Mashoes’ character in its heyday.

–10–

The origins of the Mashoes’ name are lost in mystery and lore. According to the North Carolina Gazetteer, some historians have suspected that the village’s name was of Algonquin origin, as are so many of the place names on that part of the North Carolina coast.

A more common legend, however, traces the village’s name to a man named Peter Michieux, or Mashows, about whom little is known.

According to legend, Peter Michieux, or Mashows, and his wife and child were shipwrecked near what became the site of Mashoes in the early 1700s. As the story goes, he washed ashore holding the lifeless bodies of his wife and child in his arms.

To quote the Gazetteer:

“When he regained consciousness, he found both were dead. The shock of the experience shattered his reason, and 20 years later he sat with his back to a cypress tree and died. His skeleton and a board on which he had rudely carved the account of his tragic experience were discovered years later.”

People have told many other tales about the village’s name, but it is clear that the marshy stream that led into the settlement was called “Peter Mashoes Creek” by the 1770s.

–11–

Tom Midgett’s campaign to get a road to Mashoes was successful. A state contractor finished building the road in 1943. By then, the coming of the Second World War, with young people joining the military and new opportunities to work in shipyards and other defense industries, had thinned the village’s population even more.

But on a lovely summer day, perhaps 20 or 30 locals joined a larger crowd of visitors in Mashoes to celebrate the opening of the new road.

Speeches were made, and one and all enjoyed a dinner of fried spots, Cole slaw, and cornbread prepared by Bob Tillet, an African American man who was the longtime master of community fish fries on Roanoke Island, according to June 14, 1943, Greensboro News & Record.

Maybe Mashoes’ days were numbered anyway, but the coming of the road still seemed to change everything. The village’s remaining residents found the road to be a great convenience. On the other hand, they also discovered that the convenience came with a price.

The very next year, in September 1944, a powerful hurricane washed the Methodist church in Mashoes off its foundation. The church had long been the center of community life, but now that they had a road, the people of Mashoes found it was easier to drive down to Mt. Carmel Methodist Church in Manns Harbor than it was to make the repairs to their own church.

The Mashoes School must have closed around the same time. Once the road was built, Mashoes’ children could be driven to a school in Manns Harbor. The days of children arriving at school by rowboat had come to an end.

A few years later, the village’s post office closed its doors for the last time. According to a Dec. 14, 1950, article in the Rocky Mount Telegram, the very part-time postmaster there had only done $30 in business all year.

Rural post offices were being closed all over the state of North Carolina at that time. “Rural Free Delivery”– mail delivered by vehicles from post offices in towns — was replacing them.

On the other hand, the road made things a lot easier for the remaining residents of Mashoes in some other ways.

For instance, Tom Midgett’s general store had not sold anything besides sodas since the 1930s, so the road made it easier for people in Mashoes to get groceries and other provisions.

A few years later, the first bridges were built across the Croatan Sound (1957) and the Alligator River (1962). With the road built to Mashoes, local residents could drive for the first time to Manteo, Edenton, and Elizabeth City and beyond.

-12-

In his Nov. 19, 1939, interview with the Greensboro News & Record, the old boatbuilder Peter Howett seemed to foresee what the road would mean for the little village.

He seemed to know that he — and his way of life — was standing in the way of history, and he turned his back on all of it.

“Electric lights, running water, roads, roads — ain’t this place good enough for you like she is,” he told a local young woman, Celia Liverman, in a conversation with the reporter.

Howett had seen how the children who “got educated” on that part of the North Carolina coast left behind their fishing boats, and in many cases left behind their old homes, too, and often were seen no more.

In school, the children learned about the outside world, and even if they did not have the wherewithal in 1938 or ’39 to leave home and go in search of a different life, that would soon change.

“They tell me there are seven kids in school now, seven kids that ought to be out learning how to fish like their daddies before them,” Howett, ever the contrarian, preached. He sounded terribly cantankerous and old fashioned, but there was genuine feeling behind his words, too.

In fact, when I was younger, and my elders remembered Peter Howett’s days, and the changes the coast underwent in those years, I often heard similar words from many of those old timers, too.

I think that they, like Howett, were not really railing against everything new and modern. But I do think that they were trying to tell me something important: be mindful of what people call Progress, because there is a loss and gain in everything, and we often do not know what we have lost until it is gone.