Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. More of his work can be found on his personal website.

I would like to share a collection of historical photographs from the National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Supporter Spotlight

They were taken by inspectors and other personnel of the United States Lighthouse Board (1852-1910) and its successor agency, the United States Lighthouse Service (1910-1939), in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Lighthouse Board, and then the Lighthouse Service, had the responsibility for building and maintaining lighthouses in the U.S., but also for placing and tending many other kinds of critically important navigational aids, including range lights, buoys, light beacons, daymarks and others.

Many of those different types of navigational aids can be seen in the selection of photographs that I am featuring here. They are all from the North Carolina coast, and they date to the years 1885-1917.

As you’ll see, they include some of the most iconic historical images of the state’s lighthouses.

However, for me the portraits of lighthouses are not the stars of the show. Even if it’s just because of their rarity and freshness, I was more drawn to many of the lesser-known photographs that I found in College Park.

Supporter Spotlight

In particular, I was excited to find so many photographs that highlight the historic use and importance of other, rather less majestic types of navigational aides. In some cases, I had rarely, if ever, seen them discussed in books and articles on North Carolina’s maritime history.

I am thinking, for instance, of the system of range lights that have guided vessels on the Cape Fear River since the early 19th century, or the far from glamorous lens lantern at Wreck Point, just off the point of Cape Lookout, that helped so many pilots find refuge from storms in the Cape’s lee.

Many of the photographs also give us a rare view of the behind-the-scenes work that was necessary to maintain a functional system of navigational aids on the North Carolina coast.

In this case, I am thinking, for example, of several photographs that I found in College Park of the U.S. Lighthouse Service’s buoy depot that was in the port of Washington for more than half a century.

Or, as another example, I might refer you to the handful of photographs that I have included here that feature the U.S. Lighthouse Board’s gas works at Long Point Island on Currituck Sound. At that remote outpost, the U.S. Lighthouse Board’s keepers manufactured the compressed gas that was used in gas buoys over a large swath of the North Carolina coast.

Those photographs may not come with some of the romantic connotations that we so often associate with lighthouses. Yet for me at least, each of them opens a window into an important, unsung part of the state’s maritime history — and helps us to see and understand that coastal world a little bit better.

— 2 —

By most accounts, the history of navigation aids in the U.S. began with the construction of the Boston Light on Little Brewster Island in 1716.

Records of buoys and beacons in colonial America are notoriously sparse, though. According to Amy K. Marshall’s “A History of Buoys and Tenders,” there are records of cask buoys in the Delaware River in 1767 and of spar buoys in Boston Harbor as early as 1780, but not much else.

I suspect that there were at least some local buoys and beacons, and perhaps a great many, on North Carolina waters by that time as well, but the earliest I have found were wooden slats positioned to mark a channel on the Cape Fear River, below Wilmington, in the 1790s.

The framework for a more national system of navigational aids in the U.S. began to take shape around that same time. Soon after Independence, the First Congress passed an An act for the establishment and support of light-houses, beacons, buoys, and public piers that placed the responsibility for navigational aides under the authority of the Treasury Department.

Navigational aids continued to have a largely local character, and often differed widely from place to place, however, until 1848, when the U.S. Congress adopted a system of buoyage with uniform shapes, colors, and numbering — the so-called Lateral System, that, with some minor modifications, is still in use today.

— 3 —

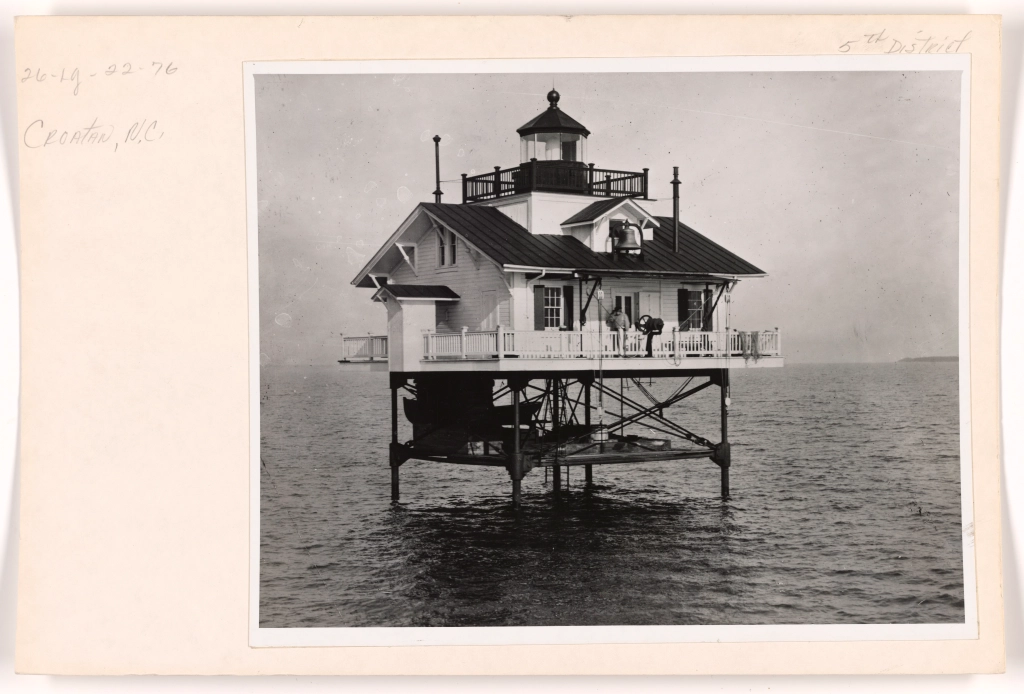

Croatan Lighthouse in the channel between Croatan Sound and Albemarle Sound in 1914.

At that time, the Croatan Light was one of 14 manned lighthouses built on piles on North Carolina waters. The Wade Point, North River, Laurel Point, and Roanoke River lighthouses all stood on the Albemarle Sound or at the mouth of its tributaries.

The Long Shoal, Hatteras Inlet, Bluff Shoal, Gull Shoal, Brant Island, Southwest Point Royal Shoal, and Pamlico Point lighthouses were all located on Pamlico Sound.

The Croatan Lighthouse was northwest of Roanoke Island. Another lighthouse, the Harbor Island Light, was located at the entrance to Core Sound, not far from Portsmouth Island, and the Neuse River Lighthouse stood off Piney Point at the entrance to the Neuse River. According to the U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office, the Croatan Lighthouse had a 4th Order Fresnel Lens, as well as a fog bell that struck every 15 seconds when in use.

— 4 —

This might be my favorite photograph of a U.S. Lighthouse Service navigational aid on the North Carolina coast. It’s a rather jerry-built back range light situated in a tree in downtown Edenton.

A front range light is evidently somewhere out in Edenton Harbor.

The front and back range lights worked together. When aligned visually, one directly behind the other, range lights indicated the route of safe passage on a river or other body of water. In this case, Edenton Harbor.

To be seen properly, the back range light had to be at least somewhat elevated above the front light, which in this case was achieved with nature’s help.

— 5 —

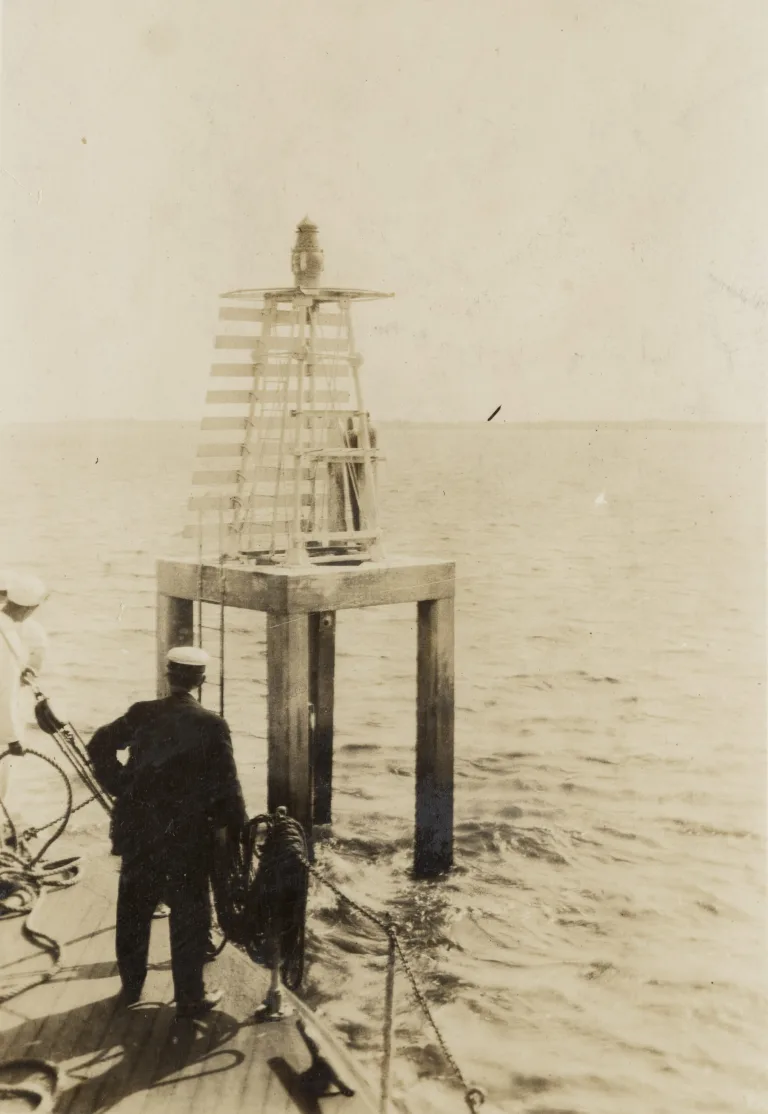

Debbie Mollycheck, who is the authority on the history of the Cape Fear river lights, recently told me that this photograph was probably taken during the Palmetto’s first inspection tour of the Lower Cape Fear.

The Palmetto had just recently been commissioned a shallow water tender. Ms. Mollycheck also informed me that the gentleman with his hands on his hips was the Palmetto’s master, Emil F. Redell. A family attorney by trade, Ms. Mollycheck is the granddaughter of Franto Mollycheck II, a later keeper of the Cape Fear river lights.

She has done extensive research on the river’s light keepers and is currently writing a history of those keepers and of the 6th Lighthouse District as a whole. You can learn more about her work online.

— 6 —

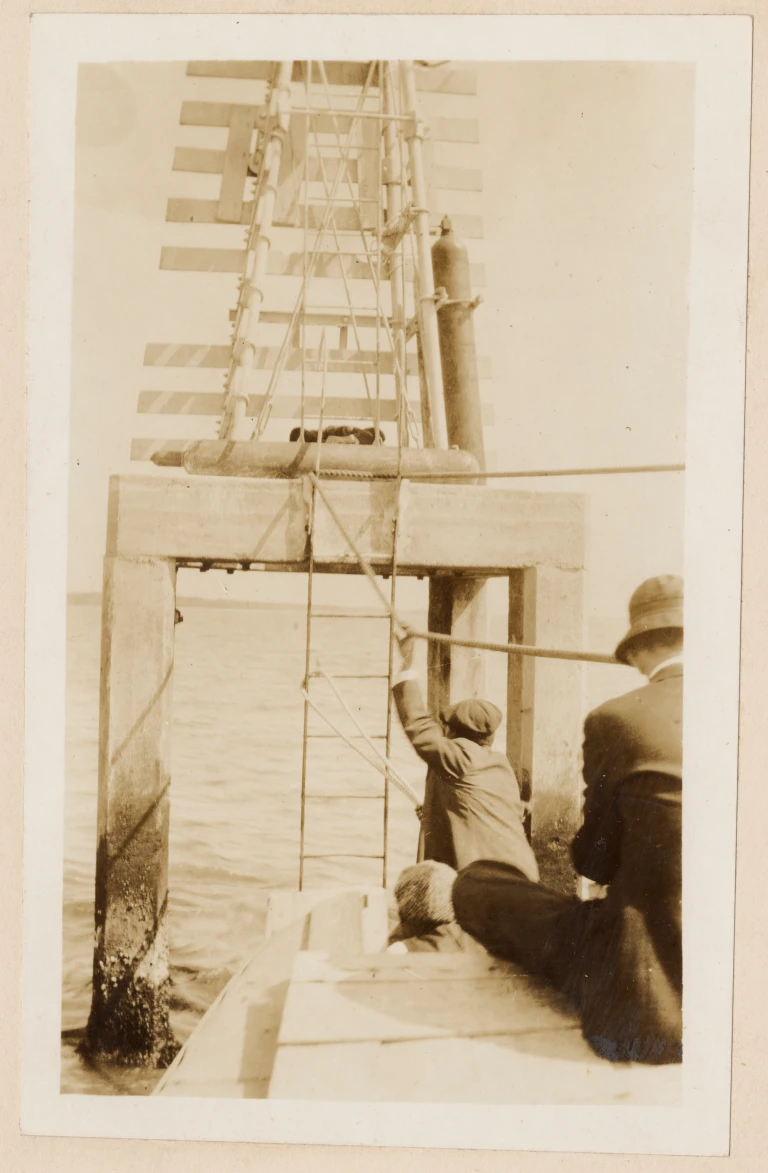

According to Debbie Mollycheck, Berry was an African American waterman who was born into slavery in Brunswick County in 1855. Her research has shown that Berry had been tending lights on the Lower Cape Fear since 1885.

At the time of this photograph, he had the day-in and day-out responsibility for maintaining the lights along a 14-mile section of the river from Upper Lilliput Channel to the Atlantic. This photograph was taken on the same inspection tour of the Lower Cape Fear that I referenced in the photograph above.

Keeper Berry was presumably guiding Capt. Redell and the Palmetto’s crew on the tour, with his boat being towed by the Palmetto and used when they needed to reach navigational aids on sections of the river too shallow for the Palmetto. You can learn more about Ms. Mollycheck’s research here, and I am hoping that I will be able to share more of her research on Henry Berry here sometime soon.

— 7 —

This is a rare portrait of the U.S. Lighthouse Service buoy depot in Washington March 1914. The depot was one of three or four in the Life-Saving Service’s 5th District, which extended from the Delaware coast to New Inlet, on the central part of the North Carolina coast.

At this site, personnel stored and maintained — painted, rebuilt, sometimes assembled — the buoys and beacons that were used throughout much of the North Carolina coast.

The depot was just below the town’s bridge across the Pamlico River, where its wharf was a popular, if apparently illicit swim spot for local kids. On the righthand side of this photograph, we can see the depot keeper’s house. In 1914, the keeper was Capt. T. F. Smith, a Life-Saving Service veteran who had previously been keeper of the Cape Hatteras Light for 19 years and the Ocracoke Light for 12 years. On the left, a side wheel steamer is docked on the Pamlico.

I can’t be sure — no Life-Saving Service tender was ever based at the depot — but the steamer looks a lot like the Sidewheel Lighthouse Tender Jessamine.

— 8 —

The U.S. Life-Saving Service used several different kinds of buoys to mark the locations of channels to warn of shoals and other dangers, and, in some cases, to indicate anchorage grounds.

Built of iron or steel plates and weighing anywhere from 700 to over 8,000 pounds, buoys such as these were moored to the bottom by a heavy chain attached to a concrete block, stone or cast-iron sinker. A cast-iron ballast ball, tethered directly below the buoy, kept them steady in rough seas and high winds.

Pilots could navigate in and out of a harbor, up or down a river or through another other kind of channel by eyeing the colors, numbers, and shapes of the buoys.

The maintenance and replacement of buoys was one of the U.S. Lifesaving Board and U.S. Lighthouse Service’s most important jobs, and a never-ending one.

As the U.S. Lighthouse Service’s annual report for 1915 said, “buoys are liable to be carried away, dragged, capsized, or sunk, as a result of ice or storm action, collision, and other accidents…, [but] great effort is made … to maintain them on station in an efficient condition, which frequently requires strenuous and hazardous exertions on the part of the vessels charged with this duty.”

— 9 —

Another view of what I believe is the U.S. Lighthouse Service paddlewheel tender Jessamine tied up at the buoy depot in Washington, March 1914.

Built at the Malster & Reaney shipyard in Baltimore in 1881, the Jessamine was based at the 5th Lighthouse District’s headquarters in Baltimore but her crew built and maintained lighthouses and tended buoys and other navigational aides across much of the North Carolina coast.

Like all U.S. Lighthouse Service tenders, Jessamine was a tough, seaworthy vessel, constructed with a hull, deck framing, and the rest of her superstructure having “a large reserve of strength,” to quote a 1915 U.S. Lighthouse Service report.

Lighthouse tenders had to be capable of handling violent storms on the open ocean, as well as to navigate along shoals where shallow draft and a solid hull, capable of putting up with accidental groundings, was required.

Note the Jessamine’s forward mast, which doubled as a derrick for construction work and for hoisting and lowering buoys. The Jessamine was not, by the way, the only U.S. Lighthouse Service tender with a botanical name.

Since 1867, the U.S. Lighthouse Service had named its lighthouse tenders after trees, flowers, or other plants, generally ones native to the area where a tender operated.

— 10 —

In June 1900, crews from the U.S. Lighthouse Service’s predecessor agency, the U.S. Lighthouse Board, placed lens lantern at Wreck Point to help guide vessels seeking a lee inside Cape Lookout.

Erected at the barb at the point of Cape Lookout Bight, the light was a welcome sight for many a mariner caught offshore in heavy weather. The Wreck Point Light gives some sense of the diversity of navigational aides built and maintained by the U.S. Lighthouse Board and the U.S. Lighthouse Service.

According to The United States Lighthouse Survey for the year 1915, the U.S. Lighthouse Service had 14,554 navigational aides in commission in U.S. waters as of that year. They included lighthouses, so-called “minor lights” that are not tended by resident keepers, light vessels, gas buoys, float lights, and a wide variety of unlighted aids such as bell and whistle buoys, fog signals, and day beacons.

— 11 —

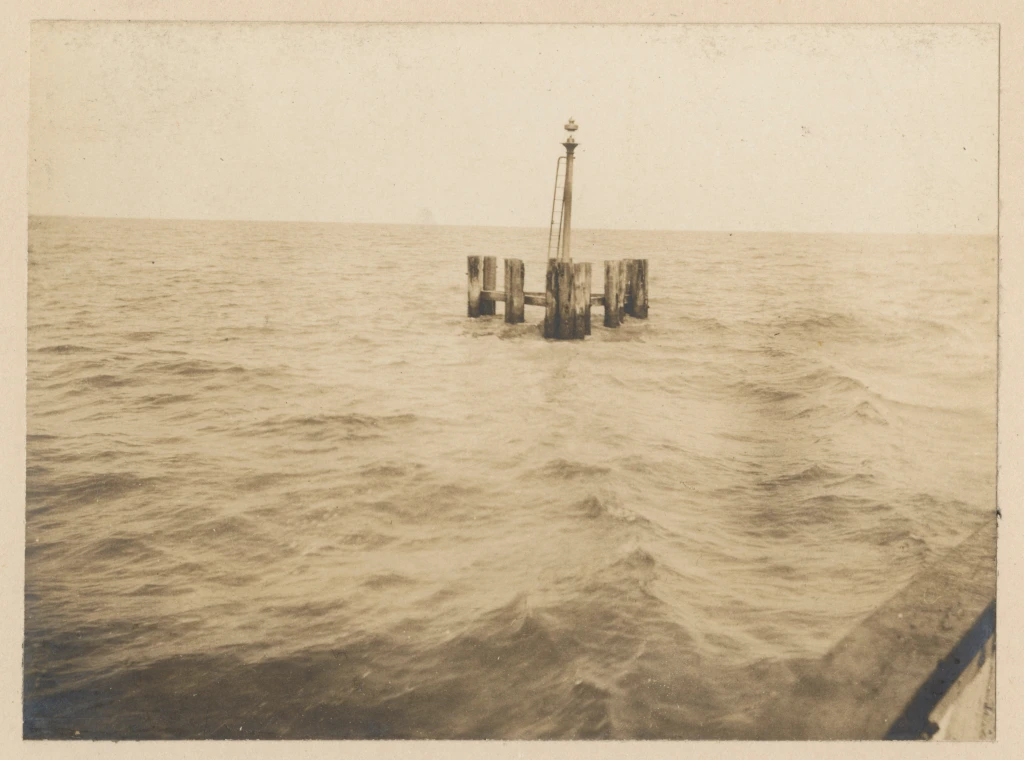

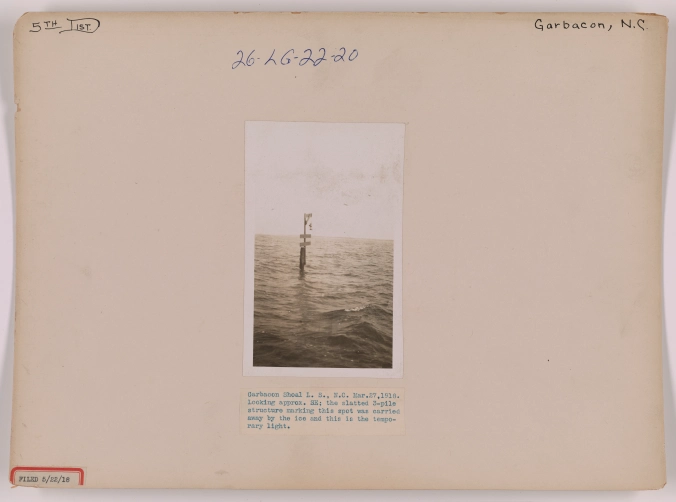

The beacon in this photograph was a temporary replacement for a slatted, 3-pile structure that was crushed by ice in the great freeze of December 1917 to January 1918.

That cold spell devastated both U.S. Lighthouse Service navigational aids and a great deal of maritime infrastructure. The ice cut away wharves and piers, took out beacons, and severely damaged at least two lighthouses. The North River Lighthouse was washed off its foundation after ice shattered its pilings. A buildup of ice also knocked askew the Norfolk & Southern’s railroad bridge across the Albemarle Sound.

According to the Jan. 25, 1918, Daily Advance in Elizabeth City, the weight of the ice made the bridge “as crooked as a snake” and a 1,000-plus foot section of the track fell into the Albemarle. Boats of all kinds were frozen in the ice; some, like the U.S. Coast Survey’s Matchless, were sunk. With no freight boats running, mail and other supplies did not reach Roanoke Island and a large section of the Outer Banks for three to four weeks.

When the ice finally broke up, U.S. Lighthouse Service crews had their hands full replacing and repairing buoys, beacons, and other navigational aids. A freeze that bad was unusual, but losing navigational aids to storms was not and kept the U.S. Lighthouse Service busy. Only a few years earlier, for instance, a 1913 hurricane destroyed 20 post lights on Pamlico and Albemarle Sound, washed out many government wharves and outbuildings, and did serious damage both to the buoy station in Washington, and to nine light stations from Ocracoke Island to Pamlico Point, according to the Washington Progress, Oct. 13, 1913.

— 12 —

The Wade Point Light Station at the mouth of the Pasquotank River was another lighthouse damaged in the great freeze of 1917-18. A screw-pile structure, the light was originally built in 1855 but was rebuilt at least once and maybe twice after Confederate guerrillas burned the superstructure during the Civil War.

It was rebuilt again in the 1890s. The station’s light and 26 x 26 cottage rested on five metal pilings roughly 12 feet above the water. During the freeze, a buildup of ice pushed the pilings to one side and left the superstructure in danger until repairs could be made to stabilize the foundation.

— 13 —

— 14 —

–15–

This is a view looking down from the U.S. Lighthouse Service tender Jessamine at the gas plant that was located at the Long Point Light Station, March 1893. Established in 1879, the station ran the gas plant in order to make the compressed gas that was used to light buoys throughout that part of the North Carolina coast.

At that time, the technology was still quite new. The country’s first gas buoy had only been deployed 12 years earlier, in 1881 at the entrance to New York Bay. Gaslit buoys were the wave of the future however. By 1915, the U.S. Lighthouse Service had more than 500 gas buoys in operation.

By then, all of the U.S. Lighthouse Service’s lighted buoys utilized compressed gas, either oil gas or acetylene. U.S. Lighthouse Service personnel deployed the gas buoys widely to mark the the entrances of rivers, inlets, and canals, as well as to signal shoals, jetties, and other dangers, as well as the paths of channels.

— 16 —

The brick building on the right is the Long Point Light Station’s retort house, where special equipment distilled and compressed the oil gas that was used in the region’s U.S. Lighthouse Board light buoys. On the left, we can see one of the two brick cisterns that were used for storing the gas. The rest of the gas works is in the background. According to research by Currituck Sound teacher and historian (and my friend) Barbara Snowden, the resulting gas was what was typically called at the time “Pintsch gas.”

Named after its inventor, a German tinsmith and manufacturer named Carl Friedrich Julius Pintsch, it was a compressed fuel gas created from distilled naphtha. Pintsch’s firm pioneered its use in buoys in the 1870s, and the U.S. Lighthouse Service used the gas extensively in buoys and other lighted navigational aides through the First World War, when it was largely replaced by acetylene.

Widely used in railroad cars as well, “Pintsch gas” could often light a buoy for a couple months or longer without refilling.

— 17 —

![Telescopic view of the Bald Head Light Station from the waters off Bald Head Island, November 1896. Originally built in 1817, the lighthouse was long a welcome sight to mariners at the entrance to the Cape Fear River. In July 1834, Capt. Henry D. Hunter of the revenue cutter Tanker described the Light as having 15 lamps, being 109 feet above the level of the sea, and showing a fixed light. On an inspection tour two years later, he reported, “The keeper is an old Revolutionary [War] soldier and is unable from sickness to give the lighthouse his constant personal attention. The light, however, shows well from a distance.” Source of quote: U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office. Source of Photograph: Records of the U.S. Coast Guard (RG 26), National Archives-College Park](https://coastalreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bald-head-island-station.webp)

Originally built in 1817, the lighthouse was long a welcome sight to mariners at the entrance to the Cape Fear River. In July 1834, Capt. Henry D. Hunter of the revenue cutter Tanker described the Light as having 15 lamps, being 109 feet above the level of the sea, and showing a fixed light.

On an inspection tour two years later, he reported, “The keeper is an old Revolutionary [War] soldier and is unable from sickness to give the lighthouse his constant personal attention. The light, however, shows well from a distance,” according to the U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office.

— 18 —

The Keeper’s House at the Ocracoke Light Station, May 1893. You can’t see it in this photograph, but the Ocracoke Lighthouse, built in 1823, is just a few feet to the north.

I would expect that the three individuals in the photo are the light station’s keeper at that time, Enoch Ellis Howard, his wife Cordelia, and one of their daughters or granddaughters. According to Ellen Cloud’s book, “Ocracoke Lighthouse,” Enoch Ellis Howard was born on Ocracoke in 1833, became keeper of the light during the Civil War, and died while still serving as the Light Station’s keeper in 1897.

He was one of many Ocracoke Howards who made their livings following the sea one way or the other as ship’s pilots, mariners, coast guardsmen, and in other maritime trades, including, some say, one who was a member of Blackbeard’s crew in the early 1700s.

Phillip Howard’s Village Craftsmen Journal is a wonderful place to learn more about the history of the Howard family on Ocracoke, as well as much else about the island’s history.

— 19 —

As I mentioned earlier, range lights are a pair of lit beacons placed some distance from one another, with the back light elevated higher than the front light. By lining up the two beacons, ship pilots could identify the channel that would afford safe passage through shallow or dangerous waters. They are sometimes used to fix position as well.

— 21 —

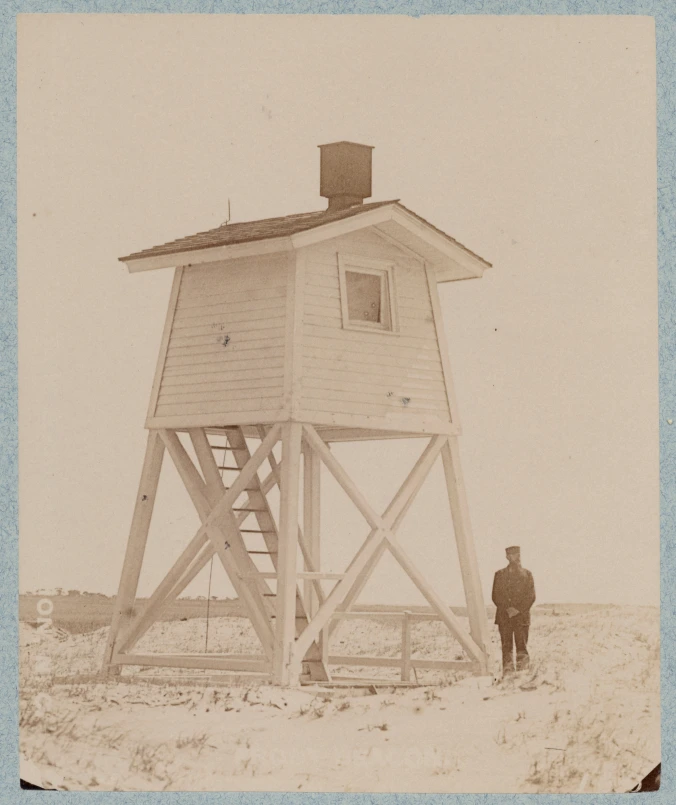

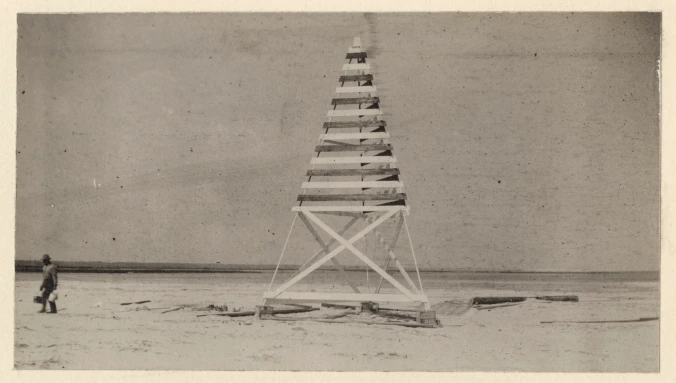

In addition to lighted navigational aids, the U.S. Lighthouse Service also built and maintained thousands of navigational aids that were not lighted– so-called “daymarks” that were only meant to be visible from sunrise to sunset. This 32-foot high structure, for instance, helped pilots get their bearings at the Little River Inlet, roughly 50 miles south of Wilmington.

— 22 —

Cape Lookout Light Station, 1889. I don’t know if I’ve seen a photograph that better captures the austere beauty of the Cape in that day and time. The building on the far right is the original Keeper’s Quarters, built in 1812 and apparently abandoned by this point in time. On both sides of the lighthouse’s base, we can just glimpse the two chimneys of the second Keeper’s Quarters, built in 1873. The two outbuildings to the right of the lighthouse are an oil house and perhaps a coal shed or other storage building.

— 23 —

These are the ruins of the keeper’s dwelling at the Price’s Creek Light Station on the Cape Fear River, just upriver of Southport, June 1917. Built in 1849, the brick dwelling had a wooden lantern that served as one of the range lights that guided vessels through the river’s ship channel.

This structure has since been destroyed by storms, but the ruins of the second range light at Price Creek, a squat 20-foot high brick tower, have survived and can be easily seen from the Southport-Fort Fisher Ferry.

— 24 —

–end–

Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who shares on his website essays and lectures about the state’s coast. He brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives where he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.