Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. More of his work can be found on his personal website.

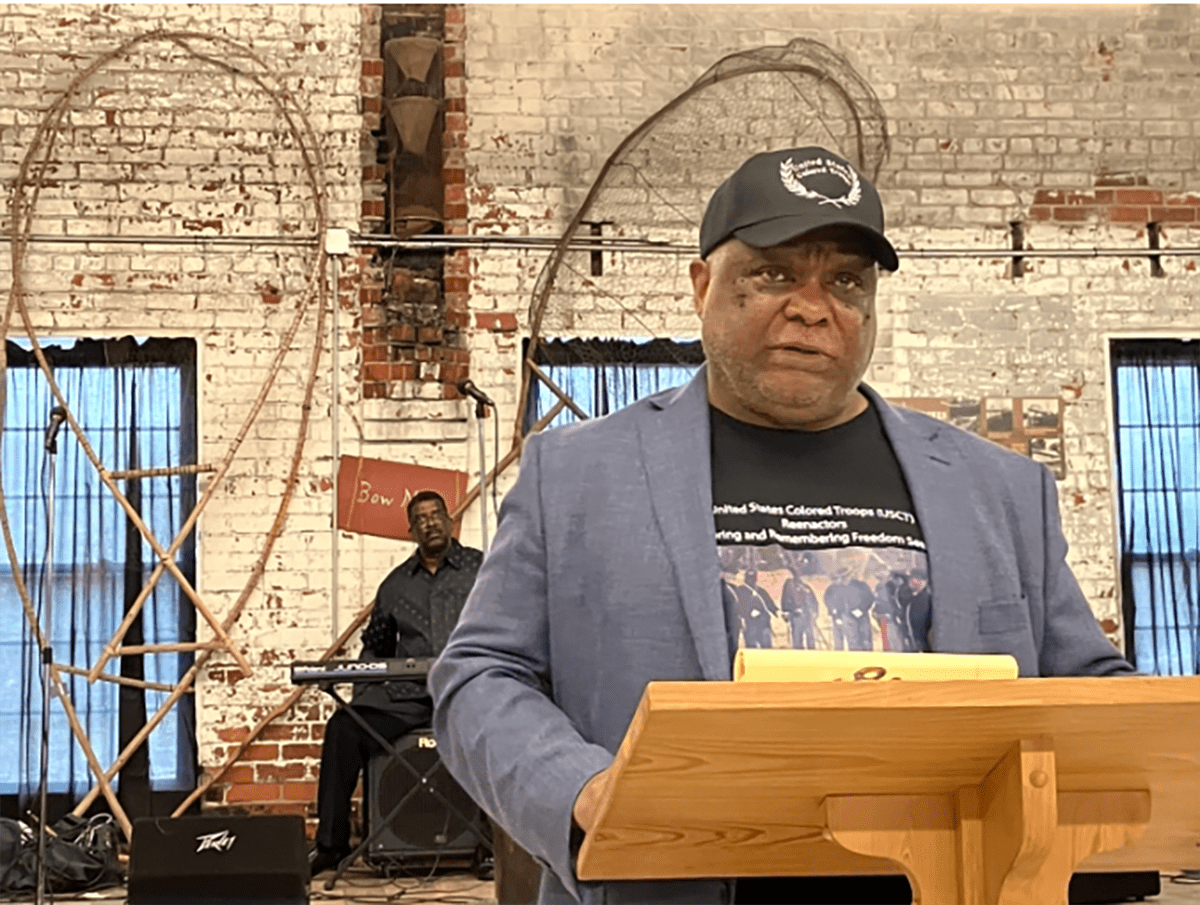

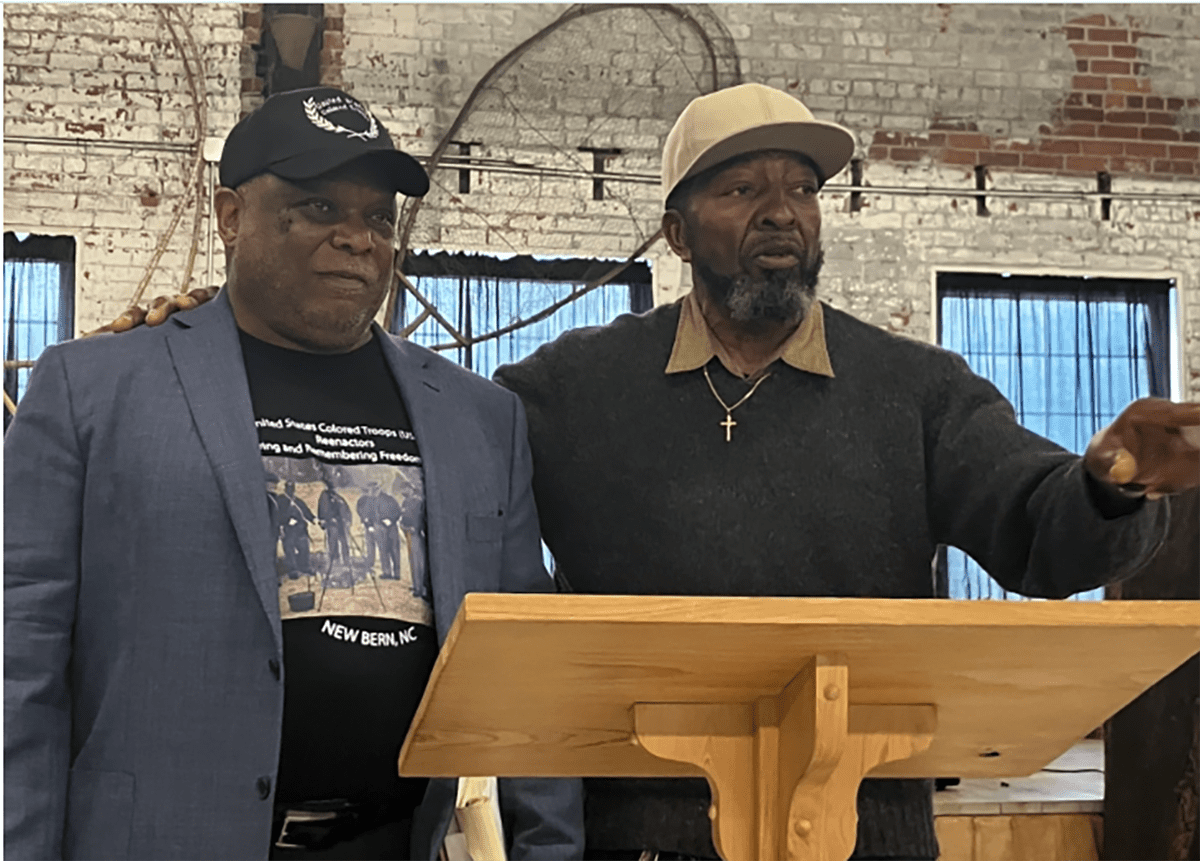

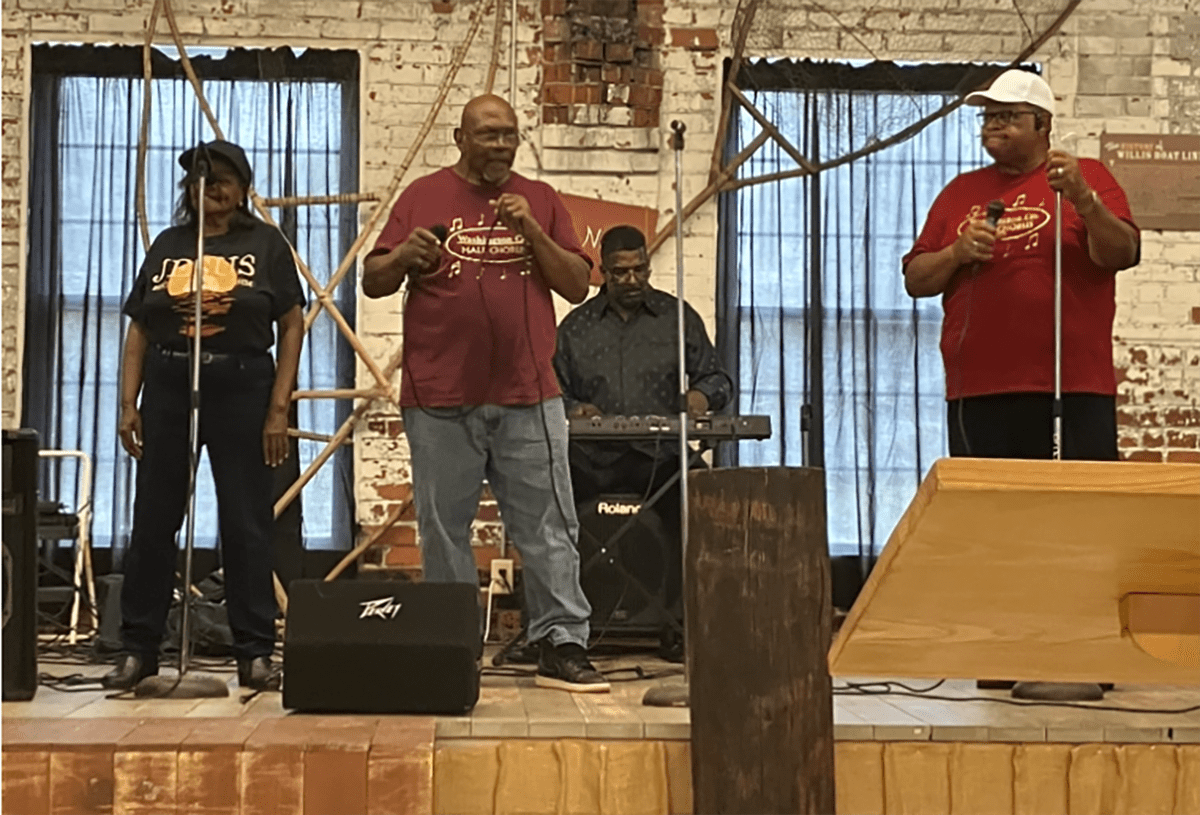

A few days ago, I gave the keynote address at an extraordinary event held in Plymouth to commemorate the Plymouth Massacre of April 1864. I found the event deeply moving, and I was honored to be there. This is a copy of my remarks.

Supporter Spotlight

Thank you for the invitation to say a few words here today. I will do my best not to go on too long, but I do feel as if some things need to be said. I of course will talk about the Plymouth Massacre. But I also want to talk at least briefly about the larger struggle for freedom, and to end slavery, that occurred here in Washington County and across the North Carolina coast during the Civil War.

I think that taking that somewhat broader view will help us to understand better what happened here in Plymouth and will help us to remember, mourn, and honor more fully those who lost their lives here 160 years ago.

In a way, I feel as if this is the funeral, the memorial service, that the victims of the massacre never had. They were unburied, left, by all accounts, where they fell, many of them in swamps where children would find their remains in the following days and weeks. No gravestones marked their passing. No monument has ever been raised to remember them.

We are here, then, to do what should have been done a long time ago. We are here to say words that for too long have not been spoken. We are here to lift prayers that are long overdue.

We are here to make sure that the forgotten will be remembered.

Supporter Spotlight

If you will bear with me, I will begin by setting the scene for what happened here in Plymouth.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Plymouth was a small town, quite a bit smaller than it is today. Most of the town’s population was African American, and the large majority of those Black men, women, and children were being held in slavery.

On the outskirts of Plymouth, on the Roanoke River, at Lake Phelps, and here and yon in every direction, thousands of African Americans were being held captive on plantations — slave labor camps, I think we would call them today, a kind of gulag of their time.

As we all know, by the time that the Civil War began in April 1861, white Southerners —and much of the North — had been treating African Americans as property, not as human beings, for more than two centuries. People, including little children, were bought and sold like mules.

That world — that way of life — finally began to crumble here in Washington County in the early part of 1862.

Very early in the Civil War, Union forces captured a long sliver of the North Carolina coast. Even before the first Yankee soldier stepped ashore, enslaved African Americans began to escape from plantations across Eastern North Carolina and move toward the sea.

Hundreds, then thousands, of African American men, women, and children fled from bondage in Confederate territory to freedom in New Bern, Beaufort, Washington, Roanoke Island—and Plymouth. As the Union force’s commanding general said, those communities were “overrun with fugitives from the surrounding towns and plantations.”

A great boatlift to freedom had begun. Across the sound here, on the Chowan River, slaves sailed away while their master shot at them from shore. Another night, a slave woman named Juno gathered her children into a dugout canoe and paddled down the Neuse River to freedom. A little east of here, at Columbia, a large group of African Americans confiscated a schooner and sailed down the Scuppernong and across the Albemarle Sound.

A little to our west, a Black boatman known as “Big Bob” carried 16 slaves down the Tar River to freedom, then turned and went back upriver for more.

Here in Plymouth, a group of slaves “patched until their patches themselves were rags” escaped and sailed through stormy weather and rough seas all the way to Roanoke Island. “How they succeeded is a wonder to us all,” a Yankee soldier exclaimed.

A little southeast of here, in Hyde County, an overseer informed a plantation’s owner that he could no longer control the enslaved men and women on the plantation, no matter what he did. Some had already escaped to Union lines. He said that he had even shot “old Pompey.”

Ten days later, that overseer reported that “something like 100 [slaves had] gone off in the last month,” 35 in a single night.

“Almost every day negroes are shot … for attempting to run away,” a journalist in Goldsboro reported. One plantation owner, William Loftin, described the situation in letters to his mother. Even before Yankee troops reached Roanoke Island, he wrote that “a good many negroes are running away” and “all of mine are gone from the oldest to the youngest.”

“All that I ever had is gone,” Loftin wrote. Later, in 1863, reality really set in. “My boy Tony came up with the Yankees in full uniform saying he was a U.S. soldier…. He went to J. H. Bryan’s and took his gun away from him. He says he has killed four damned rebels…. He had a rifle strapped to his back.”

William Loftin’s ”boy Tony” was only the beginning. By the spring of 1864, thousands of African Americans on the North Carolina coast had joined the Union army. By war’s end, nearly 180,000 African American men had served or were serving in the Union army. (Forty thousand of them did not survive the war.) Another 19,000 served in the Union navy.

The Civil War here in Plymouth was not much like the one that you or I read about in our history books when we were young (especially if you are my age) or that you may have seen in movies such as “Gone With the Wind” or even in more recent documentaries such as Ken Burns’ “Civil War.”

The large majority of Washington County’s people were opposed to the Confederacy. Half the population, we have to remember, was African American, and large numbers of the county’s white citizens also supported the Union. In fact, in Washington County, roughly as many white men enlisted in the Union army as enlisted in the Confederate army.

The divisions among the county’s white people were deep and bitter. To quote one leading historian, here in Washington County, “Brother fought brother. Neighbor attacked neighbor.”

Prior to the Battle of Plymouth, the low point was probably in December 1862, when, in a quick in-and-out raid, Confederate troops burned most of the town. (By that time, Plymouth had been in Union hands for months. Town leaders had peacefully handed the town over to the Union army in May 1862.) According to a local planter, the Rebel troops burned the town to “prevent its affording shelter to the Abolitionists and run away [sic] negroes …”

By that time, a Union private reported, Plymouth had become “a general rendezvous for fugitive slaves.” They escaped from plantations far up the Roanoke, and many got their first taste of freedom on the ground where we stand.

Many of those Black men enlisted in the Union Army. For the first time, many Black families were also able to send their children to schools that had been started here so that they could learn to read and write and do arithmetic. (None of the Confederate states allowed Black children to go to school.)

By the spring of 1864, Plymouth had been held by Union troops for nearly two years. But on April 17th, some 7,000 Rebel troops under Major Gen. Robert F. Hoke lay siege to the town, hoping to take it back from the Union and make it once again part of the slave South.

Every Black man here, both those in uniform and those that were civilians, including many fugitive slaves, understood the danger. If Plymouth fell, they could expect at the very least to be re-enslaved. But by that point in the war, most African Americans understood that, if rebel troops captured them in battle, or found them wounded on the battlefield, they might well be murdered.

By the spring of 1864, relatively well-known Confederate massacres of Black Union soldiers had occurred at Fort Pillow, Tennessee; Fort Wagner, South Carolina; Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana; Poison Springs, Arkansas; and at Saltville, the Crater, and Suffolk, Virginia.

But there were others. Many killings of Black Union prisoners did not make even a ripple in the news. Memory of them was lost in the fog of war, the slowness with which news traveled, and the reluctance, even in the North, to take the accounts of Black witnesses at face value.

The Battle of Olustee was one of those. Early in 1864, reports of a massacre of wounded Black soldiers from the 35th Regiment, United States Colored Troops, after an especially bloody battle in Olustee, Florida, reached New Bern. (The 35th had been recruited in and around New Bern.)

After Olustee, Union leaders had grown suspicious because the Confederate commander supplied them with such a short list of Union soldiers wounded or taken prisoner in the battle. But not for some months did they conclude what the surviving Black soldiers had always known, that “most of the wounded colored men were murdered in the field.”

I do not know if the Black men and women here in Plymouth knew that Confederate general Robert Ransom’s soldiers were among the Rebel troops attacking Union positions here in Plymouth. But if they did know, they would have expected the worst. Ransom’s Brigade was one of those Confederate units notorious for not taking Black prisoners alive.

Ransom’s own men wrote about that policy. Only a month earlier, Ransom’s Brigade had taken no prisoners after encountering Black troops of the 2nd Regiment, United States Colored Calvary, 75 miles from here, at Suffolk, Virginia. “Ransom’s Brigade never takes any negro prisoners,” one of Ransom’s soldiers bragged in a letter to the Charlotte Observer.

Another of Ransom’s soldiers, Pvt. Gabriel Sherrill, echoed those words. In a letter home a few weeks before the Battle of Plymouth, he wrote, referring to Black soldiers, “They will fite,” rather than surrender, “for they know that it is deth eny way if we got hold of them for wee have no quarters for a negroe.”

One of Ransom’s officers, Maj. John W. Graham, said much the same in a letter to his father. (Graham’s father represented North Carolina in the Confederacy’s senate.) In that letter, Maj. Graham said, speaking of Suffolk, the “ladies … were standing at their doors, some waving handkerchiefs, some crying, some praying, and others calling to us to `kill the negroes.’”

He told his father, “Our brigade did not need this to make them give `no quarter,’ as it is understood amongst us that we take no Negro prisoners.”

After a very bloody, four-day siege — one hard on both sides, but with especially heavy Confederate casualties — Hoke’s forces did capture the town of Plymouth on April 20th, 1864. At that point, Rebel troops were left to ransack the town and the worst fears of the Black people and the white Unionists in the town were realized.

One of the first historians to write about the Plymouth Massacre in any detail was Dr. Wayne Durrill. Durrill earned his Ph.D. in history at the University of North Carolina in 1987, and he is now a professor at the University of Cincinnati. His book “War of Another Kind“ is the fullest scholarly study of the Civil War here in Washington County.

In his book, Professor Durrill quotes the only known account of the Battle of Plymouth given by an African American eyewitness, a man who identified himself as a Union sergeant. “Upon the capture of Plymouth by the rebel forces, all the negroes found in blue uniform, or with any outward marks of a Union soldier upon him, was killed,” he testified.

The Black eyewitness also observed that “some [were] taken into the woods and hung … Others I saw stripped of all their clothing and then stood upon the bank of the river with the faces riverward, and there they were shot … Still others were killed by having their brains beaten out by the butt-end of the muskets in the hands of the rebels.”

Professor Durrill quotes another Union serviceman, a white lieutenant named Alonzo Cooper, of the 12th New York Volunteers, who reported that “the negro soldiers who had surrendered, were drawn up in line at the breastwork, and shot down as they stood.”

According to another eyewitness, when an unknown number of Black men, probably Union enlistees, saw what was happening and fired at Confederate troops, the Confederates “charged them with every conceivable weapon in their possession, whereupon the negroes [most of whom were unarmed] ran, taking refuge in Coneby Creek swamp and the flats beyond, scarcely a mile away.”

According to that account, the Rebels followed them into the swamp and “slaughtered” them “like rats.” Lt. Cooper, recalled, “the crack, crack of muskets down in the swamp where the negroes had fled to escape capture,” and reported that the Blacks were “hunted like squirrels or rabbits.”

Years later, B. D. Latham, who was a 12-year-old boy at the time, remembered that he and some other local white boys went into the swamp the Sunday morning after the battle. Professor Durrill wrote: “There they saw `hundreds of slain negro troops,’ their bodies having been left to decay for four days.”

Soon after Professor Durrill’s book was published, two highly respected Civil War historians, Weymouth T. Jordan and Gerald W. Thomas, undertook a far more exhaustive and in-depth study of the Battle of Plymouth’s aftermath. Deeply knowledgeable of the Civil War, both had, and have, reputations for being conservative, judicious, and diligent scholars.

Their goal was first to determine if what happened in Plymouth should truly be called a “massacre” and — if a massacre did occur here — how many people were killed.

At the time of their study, Jordan was the head of the Civil War Roster Project at the N.C. Division of Archives and History. Thomas, a native of Bertie County, had nearly finished his book “Divided Allegiances: Bertie County during the Civil War,” but took a break to assist Jordan to get to the bottom of what happened in Plymouth.

Together they sifted through thousands of pages of historical evidence. They then presented their results in a 72-page article called “Massacre at Plymouth: April 20, 1864.” That article was published in the North Carolina Historical Review, the state’s foremost historical journal, in the spring of 1995. To this day, it remains the definitive study of what happened here in Plymouth.

Theirs was a very cautious approach. They did not accept evidence that could not be corroborated, and they looked askance at evidence if the individual that was the source of that evidence had any reason to exaggerate or be dismissive of claims of a massacre.

At times, when I reviewed their research, I personally felt that they may have been too cautious and leant over backwards too far for the sake of wanting their research to be utterly beyond reproach.

In their article, Jordan and Thomas acknowledged that we will probably never know every detail of what happened here on those April days in 1864, or know the exact number of people that lost their lives here. Yet their findings were unambiguous. In their conclusion, they wrote, “it is clear that blacks and Buffaloes [white Unionists] were killed at Plymouth under circumstances that merit the appellation `massacre’….”

They concluded that Confederate troops, mainly Ransom’s Brigade and cavalrymen led by Col. James Dearing, executed approximately 25 Black prisoners in the first days after the Battle of Plymouth. “Some blacks captured in uniform were shot out of hand…. [S]ome were dispatched later, [and] some black male civilians were murdered also….”

They went on to say: “The number of blacks, uniformed and otherwise, who were murdered in Plymouth on April 20 was probably no more than 10. Fifteen more may have been executed on April 23 or 24…. Forty were killed as they fled the battlefield, [and] 40 were hunted down and dispatched in the swamps.” Others died in combat, hundreds of others managed to escape, and “approximately 400, including a few uniformed soldiers and many women and children, were captured and taken prisoner.”

At least a handful of “Buffaloes” — the white Unionists — were also killed either in town or in the swamps.

To me one of the war’s most remarkable phenomenon was the courage and determination that African Americans soldiers and sailors displayed even though they knew that this kind of treatment could well be their fate whenever, and wherever, they fell into Rebel hands.

“We have fought … where captivity meant cool murder on the field, by fire, sword, and halter; and yet no black man ever flinched,” African American delegates — including North Carolina’s Abraham Galloway — declared at a convention of African American leaders in 1864.

Here in Plymouth, as well as on distant battlefields, America’s Black soldiers held onto a prophetic vision of the Civil War that in their eyes justified their hardships and sacrifices.

We have to remember: their courage, and their willingness to fight and die, was rooted in something bigger than themselves and far more personal than the Union cause. Their Civil War — the slaves’ Civil War — was grounded in the love of their wives and children, their brothers and sisters, their mothers and grandmothers, their yet-to-be-born grandchildren and great-grandchildren, all of whom, if they prevailed, would be free.

If they prevailed, they knew, a child of theirs might one day go to school. A son might not be whipped to his last breath. A daughter could be raised in safety. Husbands and wives would know that they could grow old together.

If they prevailed, the unspeakable fear that a child could be taken away from them at any age, and at any moment, of any day, would disappear forever. A man or woman’s work would be their own.

A Black Union sergeant named Charles Brown expressed the prevailing sentiment among the country’s Black soldiers as well as anyone in the ranks.

While encamped near New Bern, Sgt. Brown weighed the dangers that his company faced from Confederate soldiers, as well as the discrimination that his men faced within the Union army due to their race.

And yet he wrote: “I feel more inclined daily, to press the army on further and further; and, let my opposition be in life what it will, I do firmly vow that I will fight as long as a star can be seen, and if it should be my lot to be cut down in battle, I do believe… that my soul will be forever at rest.”

As his regiment marched into battle, Brown said, they sang:

We are the gallant first

Who slightly have been tried,

Who ordered to a battle,

Take Jesus for our guide.

May all of their souls forever be at rest. May they all be remembered. May we all find hope in the stars as they did.

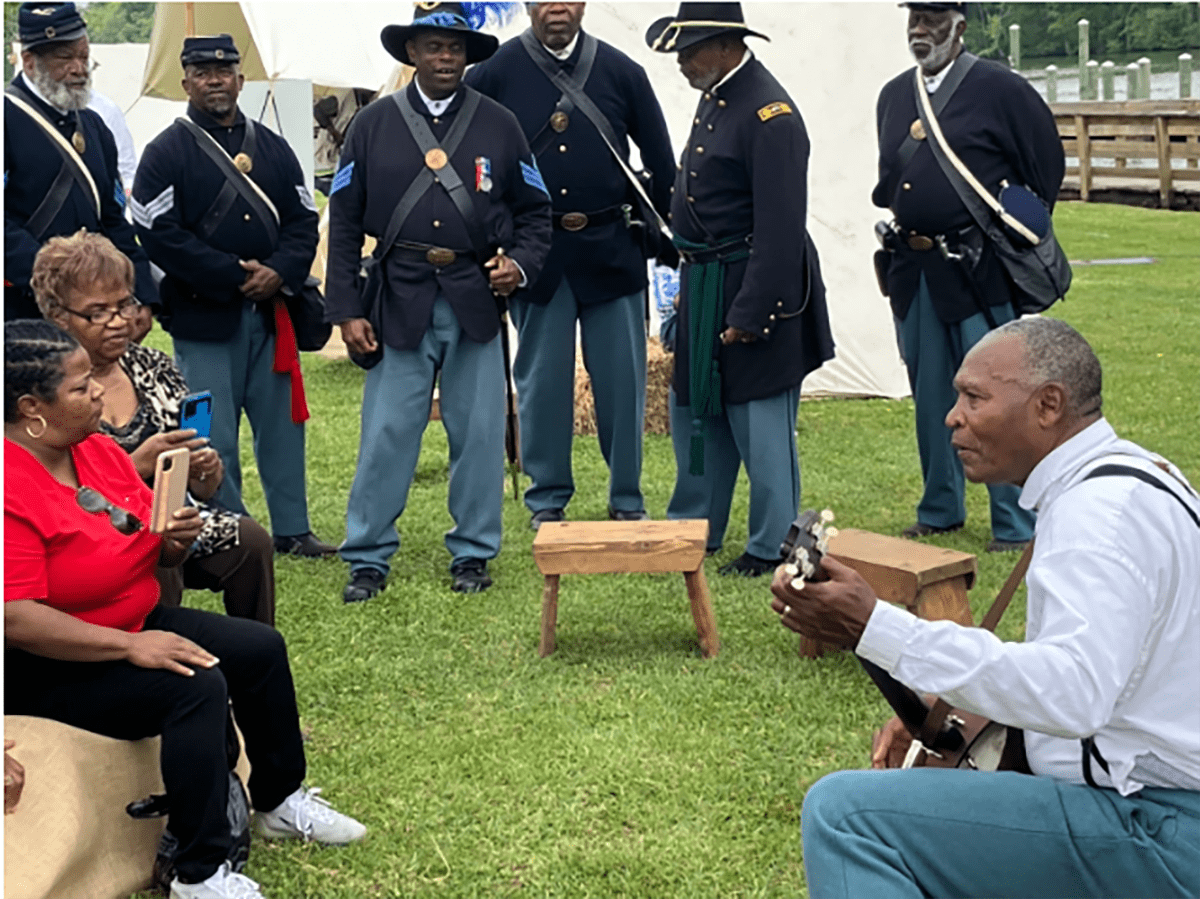

Note: Photographer Sharon C. Bryant is the African American Outreach Coordinator at Tryon Palace in New Bern, and she prepared extensive educational materials on the history of the 35th USCT that were displayed at the encampment in Plymouth.