There was little doubt that North Carolina would vote to support the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibiting “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.”

The state had been dry since 1908. The first Southern state to go dry.

Supporter Spotlight

It was the Volstead Act passed into law in 1919 that allowed enforcement of the amendment. The law was challenged in the courts, and on Jan. 5, 1920, when the Supreme Court handed down its ruling upholding the act, prohibitionists were overjoyed.

“Supreme Court’s Action Hailed as a Sweeping Victory,” exclaimed the headline in the Jan. 6 Wilmington Morning Star, with a subhead telling readers, “Dry Forces Jubilant at Upholding of Volstead Prohibition Enforcement Act.”

If the dry forces of the state saw Prohibition as the dawn of a new and healthier society for farmers and lumber workers in northeastern North Carolina, who often lived in remote and barely accessibly areas, Prohibition offered something entirely different.

It was for them, a government-sponsored golden parachute. The once seemingly inexhaustible supply of lumber had, in fact, been exhausted. In 1920, farm income was roughly equivalent to household incomes nationwide, but over the next decade and into the 1930s, as commodity prices fell and foreign competition became more robust, farm income lagged even further behind the rest of the country.

It’s unclear how much moonshine liquor was being distilled in northeastern North Carolina before the Volstead Act. Following a 1919 raid in Currituck County, W.O. Saunders, publisher of the Elizabeth City Independent wrote, “Prior to the inauguration of Bone-Dry prohibition the illicit manufacture of liquor in the Elizabeth City territory was unknown. The news in this paper last week telling of the capture of stills in Camden and Currituck counties came as a shock to the thousands who had a vague idea that ‘moonshining’ belonged to the mountain fastnesses of western North Carolina.”

Supporter Spotlight

The rare discovery of a still in these parts seems to have become more regular after the Volstead Act took effect, although it was not solely the Volstead Act that created the change.

Chris Barber, whose book “When Ghosts Made Moonshine: Prohibition in the Albemarle,” examines Prohibition in northeastern North Carolina, recently told Coastal Review about the factors involved and how the illegal practice may have started here.

“This was just making a little bit of money to feed their families originally,” she said. “There was a small depression following World War I when soldiers came back. So people needed to make money,” and Buffalo City, a logging town near East Lake in Dare County long since lost to the forest, “that was a remote location.”

Barber’s title was drawn from a 1931 New York Herald Tribune article, “A Ghost That Makes Booze,” by Ben Dixon MacNeill. The story was picked up by a number of papers including the Independent where the story ran with the headline, “Buffalo City Written up in N.Y. Newspaper.”

“The ghost makes liquor,” MacNeill writes. “Makes liquor with a prodigality and completeness that is without parallel anywhere else in this country, and liquor of an exceedingly high and desirable quality.”

By 1931, the East Lake area had become a thriving center of liquor production — mostly rye whiskey, but corn whiskey, as well.

Back in 1920, production had been small and distribution limited, although that would soon change. The federal government was unprepared to enforce the new law.

“The government provided funds for only 1,500 agents at first to enforce Prohibition across the country. They were issued guns and given access to vehicles, but many had little or no training,” the Mob Museum in Las Vegas notes on its Prohibition webpage.

Although there would eventually be more agents assigned to the area, when Robert Tuttle, the first federal Prohibition agent, arrived in Elizabeth City in February 1920, he was alone covering all of northeastern North Carolina.

Even after more agents arrived, it remained clear how ill-prepared the government was.

“The government paid them poorly,” Barber said, referring to the work that needed to be done. Cars were not provided.

In order to raid a suspected site in Camden County that borders Elizabeth City, agents had to hire jitney drivers, the equivalent a taxi. When the they arrived at the location, “It was obvious that the people they were going to raid knew it,” Barber said.

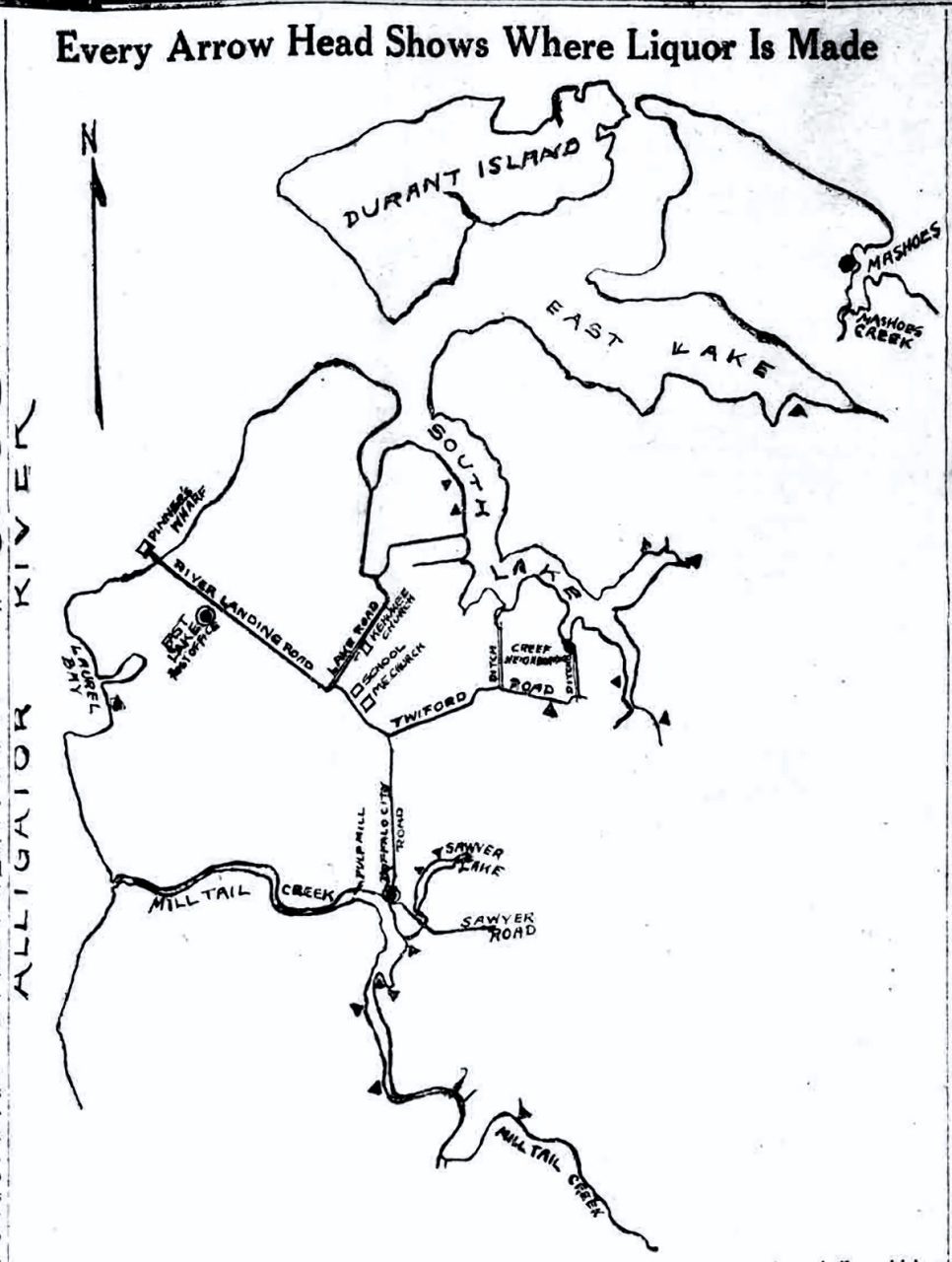

What was happening in counties close by Elizabeth City and Pasquotank County was dwarfed by what was happening on the Dare County mainland.

In the 1920s, there were no roads in the East Lake District. The main connection with the outside world was a dock at Buffalo City on Milltail Creek. The area was a virtually impenetrable swamp and sparsely populated. The people who lived there were self-sufficient and tightknit, and they had one other advantage — a well-established connection to Elizabeth City, at that time a transportation hub.

In her 2019 Eastern Carolina University master’s thesis in marine archeology, Reconstructing Buffalo City (1887-1986), Sara Mackenzie Parkin, points to the remoteness of the location and a well-established transportation network as key to an explosive growth in bootleg whiskey production.

“The strategic advantage of their remote location coupled with the proximity of well-traveled trade routes lent itself well to the illegal manufacturing and sale of Buffalo City’s newest trade good,” she wrote.

Federal Prohibition agents were aware of East Lake and in June 1922, with the help of the Coast Guard, they made their first raid.

“By nine o’clock Saturday morning they captured two sixty-gallon corn whiskey plants and destroyed nine hundred gallons of mash at East Lake. They arrested no one,” Barber wrote in her book.

Less than a year later, they agents returned. Again they arrested no one, but Barber writes, “They discovered buildings and equipment. This was more than a still; it was a large, well-organized operation.”

The agents found a still capable, they estimated, of producing 100 gallons of whiskey a day and 7,500 gallons of beer in containers ready to be shipped.

A pattern was emerging. As more federal agents arrived in Elizabeth City working with county sheriffs, they were often able to surprise bootleggers at their stills in areas accessible by car.

“Local Sheriff Found Still Running,” announced the headline in the Sept. 22, 1922, edition of the Independent. The article goes on to report the arrest of “Bruce Burgess, Henry Hughes and a 19-year-old boy named Jones.”

But at East Lake, although the agents could often seize equipment, the men who possessed the knowledge and expertise required to make whiskey were never there.

“Part of the story is the underground network and spies and informants. So agents could rarely go to East Lake and surprise anybody. It was just not possible because (East Lake residents) already knew,” Barber said.

The spies were not always successful, though. To get to East Lake, federal agents had to rely on the Coast Guard for water transportation. The AB-21, the 65-foot-long boat the Coast Guard used to cross Albemarle Sound from Elizabeth City, had a top speed of 6.5 knots, or about 7.5 mph. Almost any motorboat would be able to get to East Lake before it did.

But in August 1927 the AB-21 left after dark and anchored off Durant Island off the north end of East Lake, waiting for daylight. The strategy paid off.

“Sudden Federal Raid at East Lake Brings in Men and Liquor” according to the Aug. 27, 1927, Elizabeth City Daily Advance headline.

In the two-day raid, agents were able to arrest three men and seize “distilling equipment and supplies valued at $33,000 to $36,000.” That would be $585,000 to $638,000 in today’s dollars.

It was apparent that what was happening on mainland Dare County was distinct from anything happening in other areas of northeastern North Carolina.

“Eastlake (and) Buffalo City, liquor became more of an industrial style production. They had bunkhouses left over from timber days,” Barber said. And sometimes, “they had generators and they ran stills around the clock.”

To sustain production on that level, there had to be a way to get the product to market and the product had to be good enough to create demand. East Lake whiskey, apparently, checked both boxes. From Elizabeth City north up the East Coast to New York City, East Lake whiskey was renowned.

“Its smoothness and quality allegedly drove up demand for the product,” Parkin wrote.

This distribution network’s success relied on the active collusion of law enforcement officials here and elsewhere.

The city manager of Norfolk, Virginia, I. Walk Truxton, had learned that honest city officials were seemingly being intimidated by dishonest police and bootleggers and in 1926 he took his suspicions to Prohibition Officer Leighton Blood.

Blood came up with the idea of opening a speakeasy in Norfolk, buying illegal booze from bootleggers there. His plan did snare some 22 people, according to Barber in her book, but the speakeasy was only phase one of the plan.

Agent David Mayne came from upstate New York and he was tasked with breaking up the distribution network. To do that he set up his own still and bootlegging operation at Pierceville in Camden County. Mayne, however, was working from the Virginia Prohibition office. North Carolina Prohibition officers did not know his still had been bought and paid for with federal funds or that it was producing whiskey as part of an ongoing investigation.

On Sept. 15, 1926, North Carolina agents raided the still.

As facts emerged of what the Prohibition agents had been doing, the public was outraged.

“Facts Support Startling Charges That Government Dry Agents Had Moonshine Still Near This City,” read the front-page Daily Advance headline on Jan. 14, 1927.

The outrage, though, was not confined to local papers. Rep. Fiorello Henry LaGuardia, the prominent New York Republican, brought the actions of the agents to the attention of Congress.

On Jan. 10, 1927, Sen. James Read of Missouri introduced a measure demanding that Internal Revenue Commissioner David H. Blair, and Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Lincoln C. Andrews furnish to the Senate “copies of all orders and correspondence relative to the employment of what is known as undercover agents employed in the enforcement of the prohibition statutes.”

Included in Read’s resolution was an article in the Washington Star Ledger describing in detail the agents’ actions.

In Congress there was growing uncertainty about Prohibition. As early as 1924, Samuel Gompers, head of the powerful American Federation of Labor, sent a letter to Congress. Citing, “the lawless vender of forbidden liquor on the one side, and the lawless enforcement officer on the other, the public has suffered irreparable damage,” Gompers declared. He asked for a modification of the Volstead Act.

A 1931 congressional report showed the failure of Prohibition operations over the previous decade, concluding that, “The evidence before us tends to show a great increase in the number of stills and a universality of operating extending all over the country. The amount of moonshine liquor in this country per year can not be estimated within reasonable bounds.”

In late 1932, with newly elected Franklin Roosevelt about to be sworn in as president, Congress bowed to the inevitable. Both the Democratic and Republican party platforms called for the end of Prohibition. Support in Congress grew for a joint resolution to repeal the 18th Amendment, which the 21st Amendment did the following year.