It may be hard to overstate the influence, creativity and genius of Max Roach.

The famous coastal North Carolina native’s instrument was the drums, but calling him a drummer is roughly akin to comparing the Atlantic Ocean to a pond.

Supporter Spotlight

The subject of a PBS documentary that premiered in October 2023, Max Roach was born in 1924 in Newland Township, about 12 or 13 miles north of Elizabeth City. It might be a stretch, though, to claim Roach as a product of North Carolina. His family moved to New York when he was just 4.

If he didn’t grow up in North Carolina, it does appear as though he maintained his connection to the area.

“He wasn’t raised here. He wasn’t educated here. But he has cousins that are still here, and my understanding is that he would come back every once in a while, and they’d have a big family party out in Newland,” said Douglas Jackson, professor of music at Elizabeth City State University.

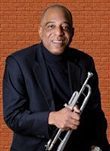

Jackson was keynote speaker at the centennial celebration of Roach’s birthday Jan. 10 at the Museum of the Albemarle in Elizabeth City. Jackson, who plays trumpet, was aware of Roach, but as he went deeper into researching him, his appreciation grew.

“I started listening to more of his recordings and what people were writing and saying about … the influence on how he maintained tempo, his cymbal technique, where he’s he’s feathering the cymbal, and it’s so fast and it’s always so consistent,” Jackson said. “People were referring to him as a lyrical drummer. He used all of the different pieces of the drum set to complement the musicians, but he never got in the way.”

Supporter Spotlight

Roach died in 2007 at his home in Manhattan, but during his lifetime, he received a number of accolades. These include a MacArthur Genius Grant in 1988, Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France in 1989 and the International Percussive Art Society’s Hall of Fame and the DownBeat Hall of Fame. In 2009 he was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame.

Roach was a musical prodigy. In an interview recorded in 1984 at Howard University, he described growing up in Brooklyn and his earliest musical experiences.

“When I was about 8 years old, I joined the marching band in Concord Baptist Church,” he said. “My first instrument in that band was a bugle. And I had a problem with that and later switched to the marching drum.”

Roach had an aunt who taught him to play piano and read music, but his love was always the drums, and by the time he graduated from high school in 1942, he was already in demand when a drummer was needed in New York City.

At age 17 he sat in with the Duke Ellington Orchestra, perhaps one of the most accomplished jazz orchestras of its day. Ellington’s regular drummer, Sonny Greer, was sick and a substitute was needed.

But, as he told NPR’s Terry Gross, host of “Fresh Air,” in a 1987 interview, Greer played by ear and by watching what was happening around him.

“I couldn’t play by ear at that time. I was about 17,” Roach said. “So Mr. Ellington, before the curtain came up, he looked at me and saw the fright of fear in my face and said keep one eye on me and one eye on the acts on the stage. And I made it through.”

That night, in spite of the fear, was also a defining moment for Roach.

“I made up my mind I wanted to be in this area of music because Duke had (it) all, the theater and the drama and the pageantry was just surrounding him when he presented a show. And that’s when I really decided that was what I wanted to do,” he told Gross.

The big-band era was coming to an end, however. There were a number of factors that led to that, but a World War II tax in particular may have been the death knell as Roach recounted in his Howard University interview.

“The Second World War, we had an extra 20% cabaret taxes,” he explained, pointing to already existing federal, state and city taxes. “On top of that (a club owner) had to pay a 20% government tax called entertainment tax. If he had a singer, if he had public dancing or dancing on a stage or a comedian, this really heralded the demise of big bands during that time.”

What did not face the cabaret tax, however, were small improvisational groups. It was a time when some of the finest jazz musicians in the world were gravitating to New York, and Roach was in the middle of it.

“Right after high school, of course, I went into New York and started working with people like Dizzy Gillespie (trumpet) and (saxophonists) Charlie Parker and Coleman Hawkins,” he recalled in his Howard University interview.

The improvisational sound of the small groups had challenges, Roach told Terry Gross.

“When you played in a small band, more was required of you because there were less people. It was like playing in a string quartet is vis-a-vis symphony orchestras,” he said. “You heard more drums, you heard more piano, you heard more this then that and the other to fill it out.”

He was 18 and 19 when he first began playing with Gillespie and Hawkins and sometimes Parker. From those sessions a new form of jazz music emerged that continues to influence how jazz is performed.

“What we hear in clubs today is a manifestation that came out of the whole bebop period, when small bands took the place of big bands and people came into these smaller clubs, sat down and listened to instrumentalists perform,” he said in his Howard university interview.

One of the most distinctive features of bebop is how the cymbal is used to keep time instead of the kick drum — it was a technique the Roach pioneered. In his first recordings in the late 1940s and 50s, there is almost no bass drum at all, but in an article written for the Percussive Arts Society, Roach is quoted from an interview published in the 1998 book “The Drummer’s Time” in which he clarified why the bass drum wasn’t heard.

“We played the bass drum, but the engineers would cover it up because it would cause distortion due to the technology at the time. There were never any mics near our feet; they would have one mic above the drum set, and that was all,” he said.

Over his career Roach went far beyond the sounds of bebop.

“The creative mind is always turning and Max had a creative mind and he kept it turning,” Jackson said, and that creative mind led to some intriguing and compelling use of percussion instruments. His 1980 album, “M’Boom,” features only percussion instruments — no stringed instruments, brass or woodwinds. The sound is complex, haunting and at times surprisingly melodic.

Music does not exist in a vacuum, Roach commented in a number of interviews, and he specifically saw jazz as an expression of the Black experience in America, and that experience is very much a part of the fabric of life in this country.

“When I look around and listen to most anybody… they have been touched by, and I mean profoundly touched, by what came out of the Black community culturally. That’s what America is,” he told his Howard University interviewer. “It reflects the whole democratic aspect, improvisation. Collective improvisation is democratic.”

He was also a powerful advocate for civil rights and African American equality. In 1960 he released “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite” featuring his wife Abby Lincoln as vocalist and Coleman Hawkins on tenor sax, with lyrics by Oscar Brown. In 2022 the album was selected into the Library of Congress National Recording Registry.

Writing about the album for the Library of Congress, writer Christa Gammage noted the album was not widely praised when it debuted.

“The album received mixed reviews; some critics claimed the album displayed a ‘bitter mood’ and felt it was ‘new-frontier club stuff and most likely a little too far out in uncut timber for most tastes,’” Gammage wrote.

Asked by Gross in the NPR interview if the album was a result of the growing Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Roach drew attention to the music Black artists had already been performing.

“I go back to Bessie Smith with “Black Mountain Blues” and then to Duke Ellington with his “Black, Brown And Beige.” It’s always been there,” he said.

He went on to tell Gross that the inspiration for his activism was what the future would hold for his children.

“You’re always thinking about … their future as well,” he said. “If they’re going to come up and be responsible human beings, they have to have education and the things like everyone else has. And the society has to accommodate that.”