Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

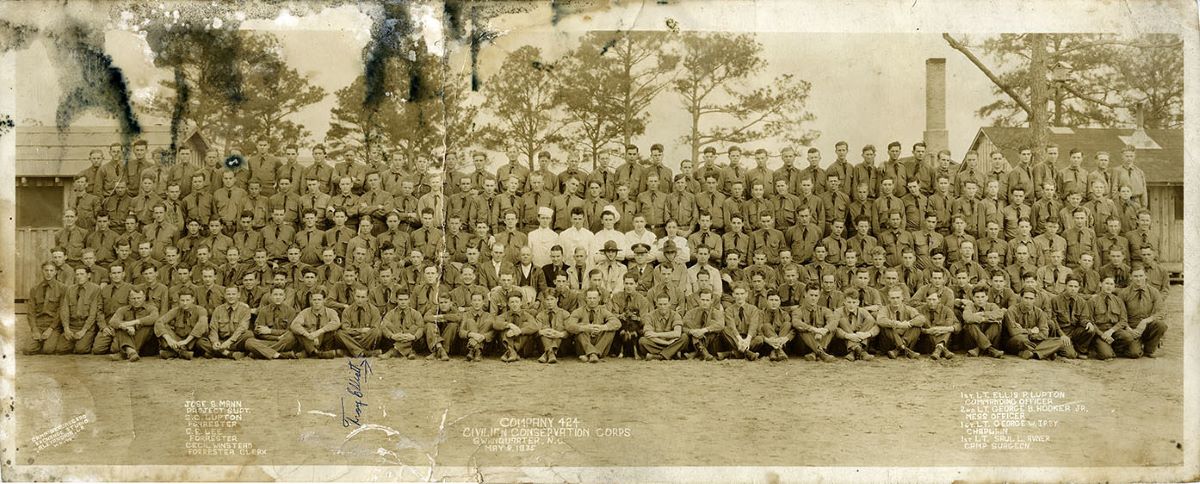

These photographs were taken at a Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC, camp on Bell Island in Hyde County in 1935, in the midst of the Great Depression.

Supporter Spotlight

Now preserved at the State Archives in Raleigh, they were taken by one of the young men who served at Bell Island. The young man’s full name was Anthony Troy Elliott — he went by Troy — and had grown up on a small farm in Perquimans County, 70 miles to the north.

Born in 1914, Elliott was one of the 200 men ages 17 to 25 who made up Co. 424 when it was at Bell Island.

Young Elliott’s photographs may not be the most artful, but I am especially fond of them because they are so full of life and yet also give us a glimpse at a part of the Great Depression on the North Carolina coast that we rarely see elsewhere.

View from the pier that Co. 424 built on Rose Bay looking back to the camp’s tents, 1935. The camp’s first enrollees came from Brunswick, Durham, Granville, Halifax, New Hanover, Onslow, and Wilson counties. Within the year, a healthy contingent of the camp’s young men also came from Hyde County, where Bell Island is located. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

Troy Elliott and his companions at Bell Island were creating what is now the Swanquarter National Wildlife Refuge, a critically important wintering ground for migratory waterfowl.

Supporter Spotlight

The CCC’s Co. 424, the top photo, was based on Bell Island from 1933 to 1937. In the autumn of 1937, the camp was closed and the company was relocated to a new site at New Holland, 14 miles to the east on the shores of Lake Mattamuskeet.

At New Holland, CCC Co. 424 did much of the work necessary to create the Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge. That work included transforming an abandoned pumping station into one of the state’s most iconic landmarks, the Mattamuskeet Lodge.

The members of Co. 424 were among 3 million young, single, unemployed men of all colors and races, whose families got through the Great Depression with the help of the CCC.

A pair of friends posing by their quarters, Bell Island, 1935. By the end of 1933, approximately 1,500 CCC camps had been built in the U.S. and its territories. Between that time and the CCC’s termination in 1942, more than 100 CCC camps were located in North Carolina. They were all segregated by race, and that number included nine camps set aside for African Americans, as well as six for World War I veterans, four for white veterans, two for Black veterans. As was the case with nearly all of the state’s anti-poverty programs in the first half of the 20th century, CCC funds were spent disproportionately for the benefit of the state’s white citizens. In the case of the CCC, the agency’s administrators maintained strict quotas on the participation of Black and Native American men. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

Created by the Emergency Conservation Work Act of 1933, the CCC was one of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs aimed at helping American citizens survive the poverty and unemployment that plagued the United States during the Great Depression.

In addition to earning wages, CCC laborers also addressed some of the nation’s most fundamental needs: building infrastructure, preserving wildlife habitat, and restoring soil, forests, and other parts of our natural heritage that in many cases had been devastated by generations of unhindered exploitation.

In the words of the Act, the purpose of the CCC was to relieve “the acute condition of widespread distress and unemployment” and “to provide for the restoration of the country’s depleted natural resources and the advancement of an orderly program of useful public works.”

The mission of the CCC laborers at Bell Island was to create what is now known as the Swanquarter National Wildlife Refuge, a 42,000-acre wetlands that provides shelter and feeding grounds for migratory waterfowl. Their work included building fire towers, fire lanes, ditching, a long pier into Rose Bay, a keeper’s house, fishermen’s camps, and a raised, mile-long road — we can see its path being cleared here — across the swamplands north of the camp that connected Bell Island to the mainland a few miles west of Swan Quarter. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

The CCCers built roads and bridges, fought forest fires, planted some 3 billion trees, carried out major erosion control projects, and built national parks, state parks and wildlife refuges.

In North Carolina, they built, or helped build, many of the state’s most cherished landmarks, parks and historic sites.

Those CCC projects included the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the Blue Ridge Parkway, the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Fort Macon State Park, the Pisgah National Forest, the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, and Waterside Theater, where “The Lost Colony” is performed, among many others.

The mosquitoes of Hyde County were and still are legendary, and one of the first newspaper reports that I found on the Bell Island camp focused on them. Appearing in the Elizabeth City Independent July 23, 1933, the article began, “Over on Bell Island 200 youthful members of the Civilian Conservation Corps are making war on mosquitoes.” Evidently much of the camp’s early work focused on mosquito control, which at that time usually meant a great deal of ditch digging in salt marshes and swamplands. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

A pair of young men fishing, hunting or just “proggin’” on one of the ditches that Co. 424 had dug at Bell Island 1935. The mosquitoes were no fun, but Co. 424’s single hardest moment was probably the great hurricane of September 1933. I know few details about the damage caused by the storm on that part of Rose Bay, but news reports indicated that the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Pamlico answered a distress call from the CCC camp and rushed there with food and supplies. Bell Island is only a few feet above sea level and the hurricane’s storm surge inevitably flooded the camp and cut off the road that the CCC work crews were building to the mainland. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

When Co 424’s camp was built at Bell Island, a quarter of all men in the United States were unemployed. Record numbers of farmers had lost their land. Across the nation, the wages of those who still had jobs had fallen on average by almost half since 1929.

In much of the rural South, the number of down and out was even higher. Nearly half of families in Dare County, for instance, just down the road from Bell Island, were on state or county relief, though it amounted to next to nothing at that time.

In the early years of the Great Depression, there was no national safety net: no Social Security, no unemployment insurance, and no federal programs to aid mothers, children, the elderly or the disabled who were in need of food, shelter or health care.

CCCers on the roadbed that they were building between Bell Island and the mainland, 1935. At the beginning, the CCC camp at Bell Island fell under the command of a Capt. Gervais of the U.S. Army’s 4th Field Artillery. That was not unusual. In 1933, regular Army officers led all CCC camps. However, by the summer of 1934, or thereabouts, they were replaced with officers from the Army Reserves. Civilians made up most of a CCC camp’s staff. At Bell Island, much of Co. 424’s original civilian staff — a clerk, a steward, medics, one of the work foremen, etc.– had been recruited in Wilson County, 100 miles to the west. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

Later in the 1930s, the Roosevelt Administration and the U.S. Congress created many of the federal programs that we now have to address those needs. Along with new legal protections for workers organizing labor unions, they made up the New Deal.

Disillusionment with capitalism and the power of banks and industry had rarely if ever been higher in American history. At the time, the nation’s business leaders widely credited the New Deal with staving off popular uprising, anarchy and even revolution.

A trio of cooks outside the mess hall on Bell Island, 1935. I do not think that I am exaggerating if I say that the opportunity to have three square meals a day was one of the most compelling reasons that young men in eastern North Carolina enrolled in the CCC. Hunger stalked the land during the Great Depression, and many of the region’s people did not have that same opportunity. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

Neil Howell, who grew up near Kinston, was 17 years old when he enrolled in Co. 424. At a reunion in 1993, he remembered his first days in Hyde County. “I was scared,” he told an AP reporter. “I had never been away from home before.” Howell soon got over his homesickness though. “We had a good bunch of people,” he remembered. Quote is from the the Greensboro News & Record, June 7, 1993. In this photo, we can see the camp’s enrollees lining up outside the mess hall at Bell Island. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

For many on the North Carolina coast, the CCC was the first tangible benefit that they received from the New Deal.

In the CCC, the young men worked for a dollar day and most considered themselves lucky. They were permitted to keep a few dollars a month for themselves, but the CCC sent the bulk of their wages to their families to help meet their most basic needs.

In addition to building the migratory waterfowl refuge, the CCC enrollees at Bell Island often continued their educations. For many, that was a rare second chance. Many dropped out of school by the age of 12 or 13, or even earlier, so that they could go to work and help support their families. In the spring of 1934, Forest Humphrey, a CCC enrollee from Jacksonville, reported that Co. 424’s civilian staff were offering classes in boat building, first aid, and in basic subjects such as reading, writing, and arithmetic. See the Belhaven Times and Hyde County Record, April 27,1934. Many years later, another CCC veteran recalled that he learned the electrician’s trade while in Co. 424. He apparently made his living as an electrician for the rest of his life. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

For many families, those wages proved the difference between abject poverty and getting by.

A $25 a month check from the CCC would not solve all problems, and a young man’s service in the CCC was limited to two years. But at least for a time, their CCC wages might stave off hunger, save a family farm, or make it possible to buy clothes so that younger brothers and sisters could go to school, among much else.

Reflecting the status of women in American society at that time, the CCC was not open to women. However, having a son in the CCC was often especially important to female heads of households who had been widowed, abandoned by husbands, or had a disabled husband, all of which were far more common situations at that time than is generally appreciated.

This photo may have been taken on Mother’s Day, 1935. A year earlier, when Mother’s Day fell on May 13, the camp’s commander at the time, Capt. Watts Cooke, had made a special request for the young men at Bell Island to write letters to their mothers “as an expression of love and appreciation.” He also authorized them to invite their mothers to visit the camp on that day, which about 30 of the boys’ mothers did. Belhaven Times and Hyde County Record, April 27, 1934. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

Interviewed in his 70s, one of Co. 424’s veterans, Ed Biggs, came from one of those families.

“Mama had a big garden and some livestock, but that’s all they had to depend on,” he told a reporter covering a Co. 424 reunion that was held at Lake Mattamuskeet in 1993.

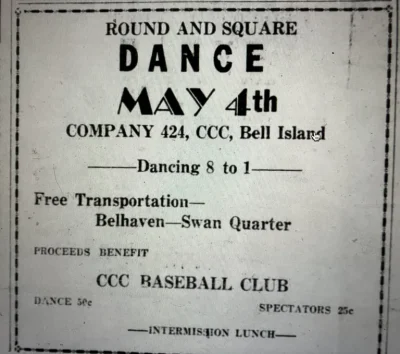

One of the most popular pastimes at Bell Island was baseball. The camp’s correspondent, Forest Humphrey, reported that his mates had organized eight teams by the spring of 1934, as well as put together a camp team to play teams in the two nearest towns, Swan Quarter and Belhaven. The Belhaven Times and Hyde County Record in Belhaven occasionally reported on their games. A July 6, 1934 article, for instance, noted that “the Bell Island baseball team played the Pungo River team here last week.” The article went on to say, “the boys have shown great spirit and took defeat from the Pungo boys– score 6-1– with a grin. The Bell Island team hopes to even up the score later on.” Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

CCC Co. 424 held dances in the rec hall at Bell Island. In the April 13, 1934, edition of the Belhaven Times and Hyde County Record, I found a notice of a dance that was held in honor a group of the young men who were finishing their CCC service and headed home. Refreshments were served. Halett Deans’ orchestra, from Belhaven, played. And the revelry lasted until midnight. With a wink to high society gossip columns of the day, Forest Humphrey gushed that the dance “turned out to be the outstanding social event of the spring season.” The CCC camp hosted another dance only a month later, on the fourth of May. The CCCers advertised the dance in Belhaven’s newspaper, and they used the proceeds from the cover charge to buy equipment and uniforms for their baseball club. From Belhaven Times and the Hyde County Record, Belhaven, April 27, 1934

Troy Elliott, fifth from left, at an ice cream social with a crowd of local friends in Hyde County, 1935. The back of the photograph identifies the group, from left, as Edward Gibbs, Hilda Midgett, Audrey Cahoon, Sybil Midgett, Troy Elliott, Eva Gray Berry, Belton Midgett, and an unidentified young woman, with Cecil Gibbs kneeling with the ice cream maker. The young men may have been among the Hyde County enrollees who served with Troy Elliott at Bell Island. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

I am sure to no one’s surprise, Co. 424 was not at Bell Island long before romance was in the air. At Co. 424’s Christmas dance on Dec. 23, 1933, a pair of weddings between the camp’s servicemen and local women were announced. Sgt. Harold D. Hampton, of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, had married Ila Mae Lee of Swan Quarter, and Cpl. Oscar Ramness, of Ada, Minnesota, had married Alice Lee Harris, also of Swan Quarter. A Rev. Lowe had performed both weddings at the Methodist church’s parsonage in Swan Quarter. Of other loves, including ones perhaps not as sanctioned, the historical record is silent. See Belhaven Times and Hyde County Record, Jan. 5, 1934. Photo courtesy, N.C. State Archives

The young men of Co. 424 were based at Bell Island for a little more than four years. Then, on Oct. 25, 1937, the CCC transferred the company to the new site in another part of Hyde County.

That new site was in New Holland, a village on the south side of Lake Mattamuskeet.

In New Holland, Co. 424’s members developed the Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge. They built waterfowl impoundments, roads, and fire breaks, as well as transformed an old pumping station into the Mattamuskeet Lodge, a three-story inn with a 120-foot viewing tower.

Through their efforts, the wildlife refuge became one of the nation’s great wintering grounds for tundra swans, snow geese, and other migratory waterfowl.

In the summer of 1993, Co. 424 held a reunion at the Mattamuskeet Lodge. One of my favorite quotes from newspaper coverage of the event was from a local woman who lived near the CCC camp when it was at New Holland. “We used to go to the dances with the CCC boys at the Barber Shanty dance hall up the road,” she recalled. “One of them was my first love, but I’m not going to tell you any names because he’s here.” Photo by Jim Bounds/AP. From the Greensboro News & Record, June 7, 1993.

Over the years, when I drive east on U.S. 264, I have turned many times onto that mile-long gravel road that leads to Bell Island and that I now know was built by Co. 424 during the Great Depression.

At those times, I always follow the road down to its end and park by the long pier that reaches out into Rose Bay.

My favorite time of year to be there is winter, even though the wind often sweeps down across the bay and chills my bones something fierce. But on those days, I am usually on my own there, or perhaps I only have to share the pier with a stubborn fisherman or two, and I am left with my own thoughts and the beauty of the place.

I can look out across the salt marshes and the bay, listen to the wild geese overhead, and, if I have timed it right, take in the glory of the sunrise or sunset.

And of course when I am there, I always think of Troy Elliott and the other young men of Co. 424 who made a home there for that brief moment back in the 1930s.

I think about the lives they left behind, and what it must have been like to be together there, and how different it must have been to everything they had known before.

I think about how it must have seemed like a stolen season, a refuge from the worst travails of the Depression years. I imagine some of them even found it a chance to glory in being young in a way that their old lives had not allowed them.

They had grown up in the Great Depression, that age of hardship, loss, and doing without. And much like our world today, their world seemed to be falling apart around them.

Many of them, including Troy Elliott, would soon find themselves in camps that did not look that much different than the one on Rose Bay, except they’d be in distant lands where bombs were dropping and cities burning and death was running riot through the streets.

When I look at Elliott’s photographs, I love seeing the happiness on their faces when they were at Bell Island.

As I stand on the pier, looking back toward the old site of the CCC camp, I never forget to think about them. I am sure they were a handful, as most of us are at that age, but when I am there I always imagine them safe and sound in their tents on a winter night.

I picture them there beneath the stars, a few lights still burning, a whisper here and there, a prayer or two, some laughter, and of course all around them the murmur of the wild geese and tundra swans.