In 1976, Walter Davis purchased 4 miles of oceanfront near Kitty Hawk for $2.1 million. It was not his first foray on the Outer Banks. The colorful oilman turned land speculator had been gobbling up large chunks of the Banks for the better part of a decade, with an eye toward controlling the oceanfront from Kitty Hawk to Corolla.

Davis, who grew up on a soybean farm near Elizabeth City, worked as a stockboy for $9.50 a week at F.W. Woolworth’s, then built a billion-dollar empire stretching from Texas to New York, wasn’t interested in building beach houses. He saw the sandy tract as an investment and one day hoped to sell it at a hefty profit. After all, he was a speculator and that’s what speculators do. They don’t get rich by betting small. They bet big. Which is what Walter Davis had been doing for decades, sometimes rashly, but almost always without regret.

Supporter Spotlight

Still, this latest purchase was different. Southern Shores was an actual development with hundreds of houses and at least that many empty lots waiting to be built. Davis was like a dog chasing a car. Now that he had finally caught the car, he didn’t know what to do. He needed help.

He turned to Charles Hayes Jr., better known as Mickey, a talented young landscape architect who had grown up in Virginia Beach and spent part of his youth frolicking on the Banks. Davis called Hayes to come visit him at an upstate office in Cary. When Hayes arrived, Davis was nowhere to be found. So, he plopped down in a chair to wait. And wait. When Davis finally emerged from an interior office, Mickey Hayes saw that he was wrapped in a spider’s web of telephone wires.

“He had three telephones going at once. It was a Sunday and he had $350,000 bet on pro football games. He was in there managing his bets,” Hayes recalled.

It is unclear if Davis won or lost that day. He bet so much, and so often, it was hard to keep score. It was a different story for Mickey Hayes. Not only did he win a job, Davis gave him “full autonomy” to finish designing and building Southern Shores, today considered one of the more attractive communities on the Outer Banks. Walter Davis’ bet on Southern Shores eventually paid off as well. In 1985, he agreed to sell the development for $6 million – or about three times his original investment.

~

Supporter Spotlight

How do you begin to describe someone who in many ways is indescribable?

Walter Royal Davis was a singular, larger-than-life American: self-possessed, enigmatic, impulsive, quick-tempered, yet wildly, even rashly, generous. Booted from several high schools for his indifference to classroom schooling, he nonetheless prized learning and later gave away millions for scholarships and libraries and was invited to sit on the boards of prestigious universities. But his philanthropy wasn’t limited to slapping his name on buildings. Stories abound in Eastern North Carolina of Davis leaving $100 tips for $1 cups of coffee. A rare raconteur who also listened closely, Davis would lean into a waitress and ask about her life and goals. If she dreamed of going to college, Davis would make it happen.

According to a family biography written by North Carolina journalist Ned Cline, Davis once paid to bring the comedian Bill Cosby to a school in Manteo as a reward to the children. By the time he died in 2008, at the age of 88, it is estimated that Davis had given away over $100 million. His generosity included his ex-wives. Davis was married six times to four different women (two, twice). Cline recounts that Davis agreed to settle one divorce for $1 million but insisted that the money be delivered in $1 bills by armored truck. That was also Davis: an unrepentant rogue. But not one you wanted to rub the wrong way.

Davis’s politics veered from Democrat to Republican, depending which party happened to be in office. He gave generously to all, millions by his count, not necessarily expecting anything in return except that the politicians would pick up the telephone when he called, which they did. Walter Davis could make or break careers and legislation. He knew everyone and, if he didn’t know someone, he quickly found a way to befriend him. When he returned to his native North Carolina from the Texas oil fields, he kept a suite at the Radisson Inn in Raleigh Triangle Park, where politicians paraded by for his drinks, advice and money. In the late 1960s, he bought a shabby motel in Kitty Hawk and spruced up one of the rooms to host all-night poker parties. Among his guests were Sen. William J. Fulbright of Arkansas and House Speaker Thomas “Tip” O’Neill. He also knew Henry Kissinger and Dean Rusk, and once socialized with French President Charles de Gaulle, according to his biographical sketch.

When young Marc Basnight was considering a run for the North Carolina Senate in the 1980s, Davis pulled him aside and told him he wasn’t ready. Still, he saw something. Like Davis, Basnight had barely escaped high school yet was preternaturally smart and good around people. Davis bought Basnight a subscription to The Economist magazine and quizzed him weekly while they tooled around Manteo in his Lincoln Town Car. When it appeared Basnight wasn’t keeping up, Davis called him stupid and advised the would-be politician to pick up the pace. Basnight won his election and went on to serve as Senate pro tempore, the second-most important position in North Carolina politics. Visitors to his Raleigh office recalled it being filled with magazines of all stripes — many of which were dogeared or marked-up. Clearly, he had gotten the message. Dumb wasn’t going to cut it.

~

After quitting Woolworth’s, Davis rotated through different jobs, working as a long-haul trucker, office manager and restauranteur. He spent three months in federal prison for failing to pay business taxes, then relocated to Salinas, California, where he met another rebellious entrepreneur, Fred Rumbley, who quickly recognized Davis’s innate business savvy. The pair worked profitably together for a quarter-century. In the 1950s, Rumbley backed Davis on a new venture: hauling oil from wells to refineries in the booming Texas Panhandle. Davis moved to Midland, the hard-driving, hard-drinking center of the oil fields, and began buying tanker trucks and making friends, including the future president, George H.W. Bush. The flamboyant Davis became so popular, bartenders named a drink for him at the Midland Petroleum Club – the “Walter Davis,” straight Seagram’s VO over ice, according to Cline’s biography.

After a number of years, Davis was hauling a half-million barrels of crude a day and making millions for the Rumbley-Davis partnership. In time, he would branch out, adding real estate and manufacturing businesses, and his wealth would grow to preposterous levels. But the Texas Panhandle was brutally hot in summer and Davis decided to split his time at a Nags Head bungalow he bought. In the late ’60s, he began to invest in Outer Banks real estate, picking up a home here and there, the old Sea Ranch Motel, even a fishing pier.

Davis had more stories than a dog. One that stands out is how, one summer day in 1968, he was looking for a bottle of Orange Crush soda on a Kitty Hawk pier. When he couldn’t find one, he complained to the pier manager, who apparently didn’t recognize Davis and told him, “Tough,” and if he didn’t like it, he should buy the pier. Which Davis did, writing a check on the spot for $96,000. A decade later, he sold the pier for $2.5 million – a testament to Davis’s skill, luck, and the soaring real estate values on the Outer Banks.

About this time, Davis was introduced to Armand Hammer, volatile chairman of the board of Occidental Petroleum. The meeting was arranged by North Carolina Gov. Terry Sanford and took place at an Outer Banks marina, where Hammer’s yacht docked beside Davis’s prized boat, Gemel 1. Initially, Davis liked Hammer. He was an impulsive gambler, like him. Two years later, he merged his oil business with Occidental. It would prove to be a horrible mistake, Davis would later say. The worst decision he ever made.

In the late ’60s, Davis began to buy large tracts along the pristine Currituck Banks, including 4 miles of oceanfront for $1.2 million from the members of the Currituck Shooting Club. He used Carl P. White, a legendary waterfowl guide and hunt lodge manager who speculated in land on the side, as his proxy. White acquired an option and then sold it back to Davis.

A year later, Davis turned to White again, this time to buy the Pine Island Hunt Club, which had been owned since the 1930s by the Barney family from Connecticut. The tract included roughly 5 miles of gently rolling sand dunes, interior forests and sprawling salt marsh from the Atlantic Ocean to the Currituck Sound. Davis, then a vice president of Occidental, used a company subsidiary to pay for the $2.5 million option on the land. According to legend, when Hammer learned about the deal, he quickly canceled the payment. Not long after, an embittered Davis left Occidental.

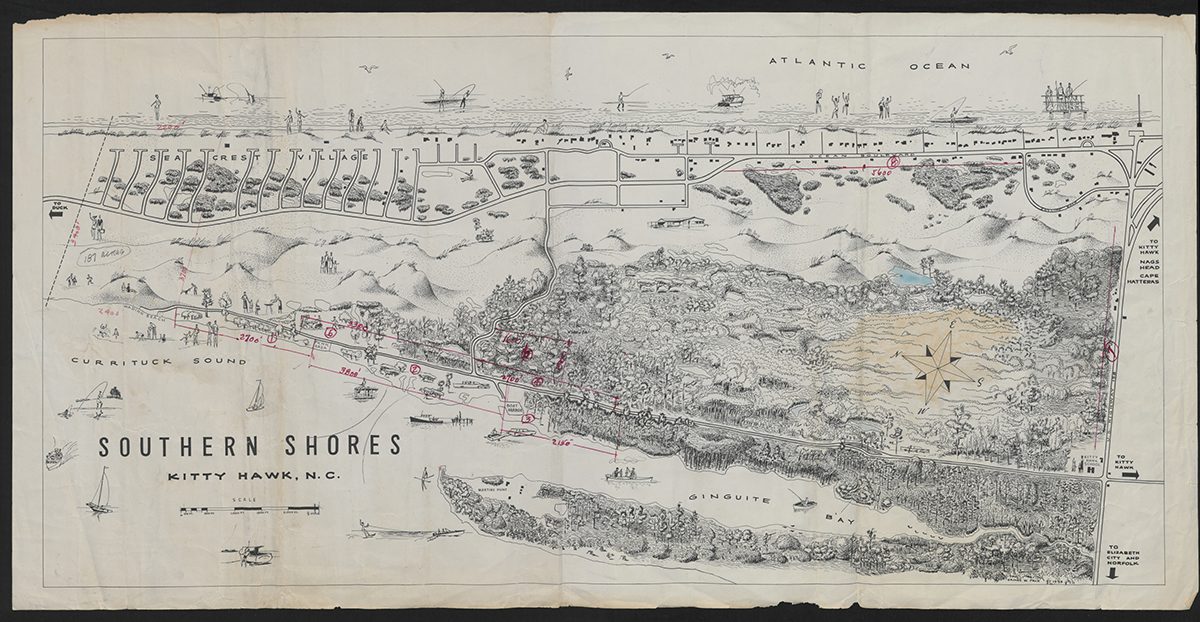

With his plans to control the Currituck Banks scuttled, Davis sold the Currituck Shooting Club land to James Johnson and Coastland Realty, which developed the popular Ocean Sands resort. But Davis wasn’t quite done. In 1976, he purchased the 2,700-acre Southern Shores property from David Stick, the local historian and developer, who was having money issues. Davis and Stick had become friends while working together on the initial Coastal Resources Commission Advisory Committee a few years earlier. Stick was divorced and in debt and wanted to devote more time to his writing. According to Mickey Hayes, “Mr. Davis thought a lot of David. He had no interest in the real estate. He wanted to help David and that is what he did.”

Davis left Hayes to finish Southern Shores. Hayes said he worked tirelessly during the day laying out the undeveloped lots, “trying to make the houses fit the land,” and his nights designing houses on the side. One house he designed was for Davis along the northern oceanfront in Southern Shores. Hayes laid it out horizontally, not vertically, like most beach houses today. “It was a huge house and had everything you could put in there,” he said. “It didn’t matter what it cost. Mr. Davis said: `Do what you can do.’ And I did.”