Frank Stick was in search of two things when he arrived on the Outer Banks in the 1920s: adventure and money. He found enough adventure to fill a lifetime but like many Bankers on the isolated barrier islands, he scrambled to pay the bills. Once one of the largest landowners, with property from Kitty Hawk to Hatteras, the artist turned developer lost many of his holdings during the Great Depression. Stick eventually recovered and developed the much-admired Southern Shores community with his son David and other partners. A complex man of shifting interests and unwavering opinions, Stick was both a conservationist who played an instrumental role in the formation of Cape Hatteras National Seashore and an avid land speculator who wrote of turning the Banks into a playground for tourists.

This is his story.

Supporter Spotlight

Chapter Four: Inventing the Seashore

In the 1930s, with the nation in the throes of the Great Depression and any signs of a land boom now a distant memory, Frank Stick shifted tactics and returned to his role as a conservationist.

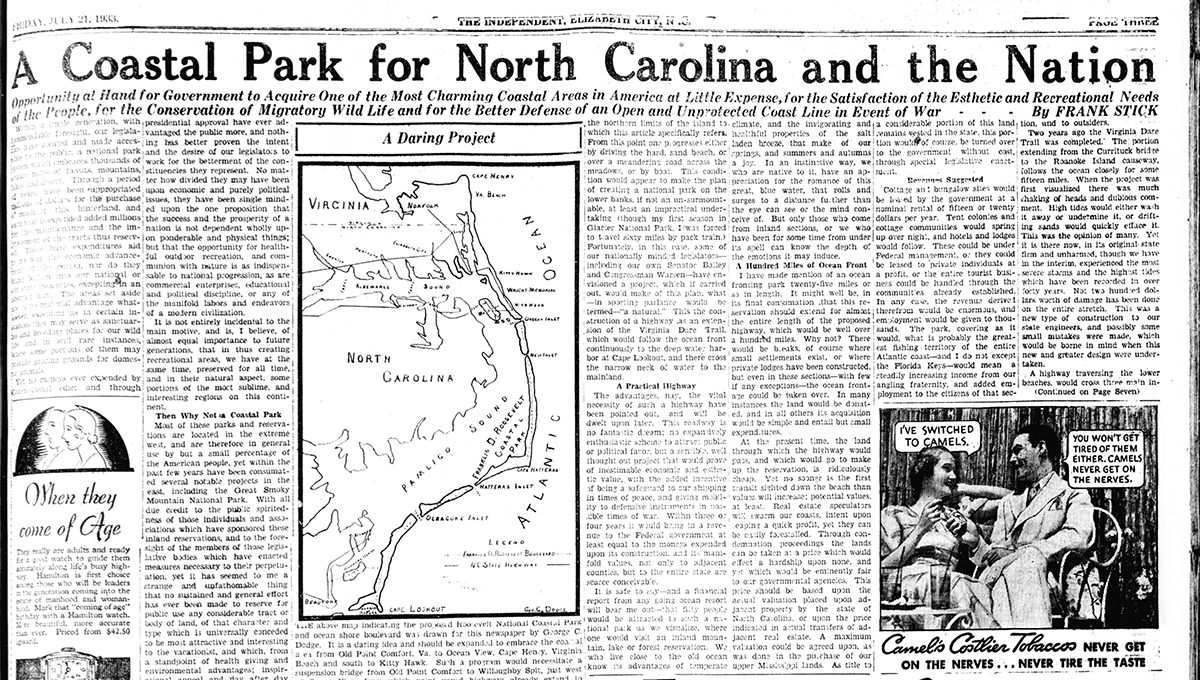

Writing in the July 21, 1933, edition of The Elizabeth City Independent, Frank outlined a sprawling new vision calling for the government to set aside a large share of the Outer Banks as a park. Entitled: A COASTAL PARK FOR NORTH CAROLINA AND THE NATION, Frank argued that the government had scores of beautiful parks out West – Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, among others – but barely any presence in the East, and nothing along the coast. Why not a park for the Outer Banks? he asked. The low, slim barrier islands included miles of “shining beaches, peaceful sun-kissed sounds, and bountiful wildlife.”

Frank’s cri de coeur took up an entire page of W.O. Saunders’s broadsheet. That by itself should have signaled to readers that Saunders favored the idea. In fact, a decade earlier the editor had called for a state park in Hatteras in his newspaper. Frank Stick’s plan was far more elaborate, taking the readers through the logic for a park, where it might be located, and how it would boost the isolated Banks and its faltering economy.

Frank began by telling readers that the “opportunity for healthful outdoor recreation and communion with nature” was an indispensable part of America’s progress as a nation — as important as commerce, politics or education. Unfortunately, he continued, speculators had acquired the majority of the nation’s shoreline for private development. With so much land tied up in private hands, ordinary citizens would have dwindling opportunities to experience the serenity and beauty of the seashore.

Supporter Spotlight

At first blush, it might seem odd that Stick, one of the largest title holders on the Outer Banks until the Depression, would single out speculators. However, it is worth remembering that Frank never saw himself as a real estate man greedily buying up the oceanfront. In his mind, he was a conservationist striving for an equitable balance between development and nature. Was it true? Not exactly. He landed on the Banks with a plan and needed to make money in real estate after abandoning his art career. Still, his later developments, especially Southern Shores, did achieve some of the balance he sought.

Frank proposed that the government should acquire up to 100 miles – or most of the Banks – via philanthropic gifts, condemnation, and outright purchases. The Outer Banks, he wrote, were “unique among all lands on the earth,” enjoyed a mild year-round climate, and rarely experienced hurricanes. Contrary to popular narratives, he added, meteorological records showed that the Outer Banks were no windier than the New Jersey coast where he had lived for more than a decade. It was a bold claim and likely made to boost his park plan. In private correspondence, Frank often complained about the relentless wind on the Outer Banks. Indeed, only months after writing his proposal, a hurricane struck the Banks, leveling Frank’s pavilion on Kitty Hawk Bay.

At the time, there was only a small section of paved road on the Banks, paralleling the ocean from Kitty Hawk to Whalebone Junction. Frank envisioned constructing a highway the length of the Banks. With his usual confidence, he explained to readers: “This roadway is no fantastic dream; no expansively enthusiastic scheme to attract public or political favor, but a sensible, well thought out project that would prove inestimable economic and esthetic value …”

Frank calculated that a seashore park would attract 50 visitors for every one visitor to an inland mountain, lake or forest. He wasn’t wrong; a seashore park would draw large crowds. But his numbers were wildly exaggerated. In recent years, even with up to 3 million visitors annually, Cape Hatteras National Seashore ranks well behind the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, with its nearly 13 million visitors. Indeed, none of the National Park Service’s 10 national seashores crack the top 10 in attendance for its many parks.

Frank ended his proposal by suggesting that a seashore park could be dedicated to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the newly elected president. It was a savvy political move but probably unnecessary. The administration was already looking for projects for its New Deal relief programs and had embraced legislation calling for the development of recreational areas and public parks. Within a year or two, the Work Progress Administration (WPA) and Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) would employ thousands of jobless and homeless Americans, using them to clear and maintain forests, build camps, repair wildlife refuges, and scores of other jobs. The men would provide a ready source of cheap labor for a seashore park.

The idea of a seashore appealed to National Park Service officials, who, like Stick, worried that the nation’s coasts were being bought up by wealthy Americans, shutting out everyone else. “When we look up and down the ocean fronts of America, we find that everywhere they are passing behind the fence of private ownership,” wrote Harold Ickes, Secretary of The Department of Interior, which includes the National Park Service.

The Park Service sent Marion Shuffler, a researcher, to study the possibility of using the Outer Banks as America’s first national seashore. Shuffler reported back that the economy of the Outer Banks was in serious decline “and tied to a way of life that no longer exists.” He then argued that the future of the Banks depended on tourism, tied to a park. A subsequent study identified a dozen possible locations for federal seashores but settled on the Outer Banks as the best choice.

The momentum was now behind Frank’s proposal. All he needed was for the politics to align.

~

Frank Stick didn’t think of himself as a political person. He called himself “a lefty” but that appeared to be a joke. He complained about some of the New Deal programs and criticized government bureaucrats who never acted quickly enough for his mercurial tastes. If anything, his politics veered more Republican than Democratic.

In a strange twist, in 1940, the FBI office in Charlotte opened an investigation of Frank after they received information that “Frank Stick is an individual who is in favor of dictatorships and opposed to the democratic form of government in this country,” records show. Edward Scheidt, the Special Agent in Charge, asked Victor Meekins, the Dare County Sheriff, to investigate. A few days later, Meekins wrote the agent that Frank had originally been a Republican but was now trying to “adjust himself … to Democratic sentiment.” Meekins added that Frank appeared to be loyal to his country but perhaps became confused at times. “With a world gone hay-wire, he probably is perplexed himself, and scatters remarks without discreetly remembering who is listening.” The Bureau dropped its probe.

After being appointed to a state commission established to promote an Outer Banks park, Frank bristled at the slow pace of those working with him and sometimes took matters into his own hands, traveling to Washington and Raleigh to push his proposal. Over the next few years, Frank worked tirelessly on his vision and was a relentless letter-writer to politicians and key government officials, urging them to move more quickly.

In Frank’s mind, the window for a park was limited. Residents of the Outer Banks had responded favorably to his proposal. But Frank knew there were limits to their enthusiasm. Like him, they had a tenuous relationship with the government. They liked when the government built them roads and bridges. But they worried that the park might be a land grab and restrict their ability to move about freely, hunting and fishing. Their concerns – as well as missteps by the government, and the coming war – would delay the seashore for years.

Park Service officials admired Frank’s energy and dedication, especially Conrad L. Wirth, a Washington, D.C.-based administrator who helped to plan the National Seashore and eventually would be named NPS director. Publicly, Wirth praised Frank. But privately he worried that Frank had “ulterior motives” and might be pushing the park to boost the value of his remaining real estate. It was a classic case of supply and demand. If the government controlled large swaths of the Banks, the remaining land in private hands would go up in price. In a letter to Maud, Frank once noted that if the park were approved, it would be good for them and might help to turn around the family’s fortunes. Of course, Frank wouldn’t have been the only one to benefit. In any event, the two ideas, pushing for a large swath of the Outer Banks to be preserved and encouraging a vibrant tourist economy, weren’t mutually exclusive in Frank’s mind.

Throughout this period, Frank worked closely with Lindsay C. Warren, the congressman from nearby Washington, in Beaufort County, who represented the Outer Banks. Like Stick and others, Warren saw the future of the isolated barrier islands as tied to tourism. Warren was young, 36, ambitious and eager for headlines. In 1937, he introduced legislation in the House to create the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, and also played an instrumental role in directing millions of New Deal dollars to Eastern North Carolina and the Banks.

When FDR unveiled the WPA and CCC, Warren saw an opportunity and began lobbying the administration. In May 1935, FDR invited Warren to spend a weekend on his yacht, Potomac, along with Harry Hopkins, the President’s right-hand man on the New Deal. Two weeks later, Warren announced that the WPA was setting aside over $1 million dollars to fight erosion and help “stabilize” the Outer Banks.

Like most barrier islands, which are constantly shifting, the Outer Banks suffered from chronic erosion. The problem was especially acute near the historic Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, which was being undermined and was at risk of collapsing into the Atlantic Ocean. Following publication of Frank’s proposal, a cadre of state foresters and geologists visited the Banks to study the issue. They concluded that the Outer Banks (let alone a park) would not survive without human intervention. They proposed a towering artificial sand dune to prevent sand from washing across the islands in storms. The barrier would extend from the Virginia border to Ocracoke Island.

Frank never mentioned erosion or the supposedly ragged condition of the Banks’ sand dunes in his proposal. Nevertheless, he quickly endorsed the idea as his own, contending that a stable dune was needed to protect the asphalt road he envisioned running the length of the Banks. Later, he directed a crew at one of the eight government camps on the Banks that housed thousands of itinerant workers building the dunes.

Years later, in 1973, the NPS would abandon its dune-building activities. Erosion was a natural part of barrier island migration, scientists said, and blocking sand from washing across the islands and elevating the interiors was a mistake. The artificial dune also provided a false sense of security, the scientists wrote, encouraging development in areas prone to flooding and storms. By then, the Service had spent millions of dollars moving around sand. State engineers had spent millions more.

America’s first national seashore didn’t officially open until 1953. By then, Frank Stick had moved on to new ideas and interests, including new real estate deals. His son David would assume the family lead in helping the seashore into existence, working closely with state and federal officials, writing articles, and giving talks.

Next in the series: Southern Shores