Frank Stick was in search of two things when he arrived on the Outer Banks in the 1920s: adventure and money. He found enough adventure to fill a lifetime but like many Bankers on the isolated barrier islands, he scrambled to pay the bills. Once one of the largest landowners, with property from Kitty Hawk to Hatteras, the artist turned developer lost many of his holdings during the Great Depression. Stick eventually recovered and developed the much-admired Southern Shores community with his son David and other partners. A complex man of shifting interests and unwavering opinions, Stick was both a conservationist who played an instrumental role in the formation of Cape Hatteras National Seashore and an avid land speculator who wrote of turning the Banks into a playground for tourists.

This is his story.

Supporter Spotlight

Chapter Three: Setbacks to A Dream

The Elizabeth City Independent’s publisher W.O. Saunders liked Frank Stick. He thought he was a dreamer and an artist with a worthy plan to transform the isolated Outer Banks into a national destination for tourists and create thousands of jobs and unprecedented wealth.

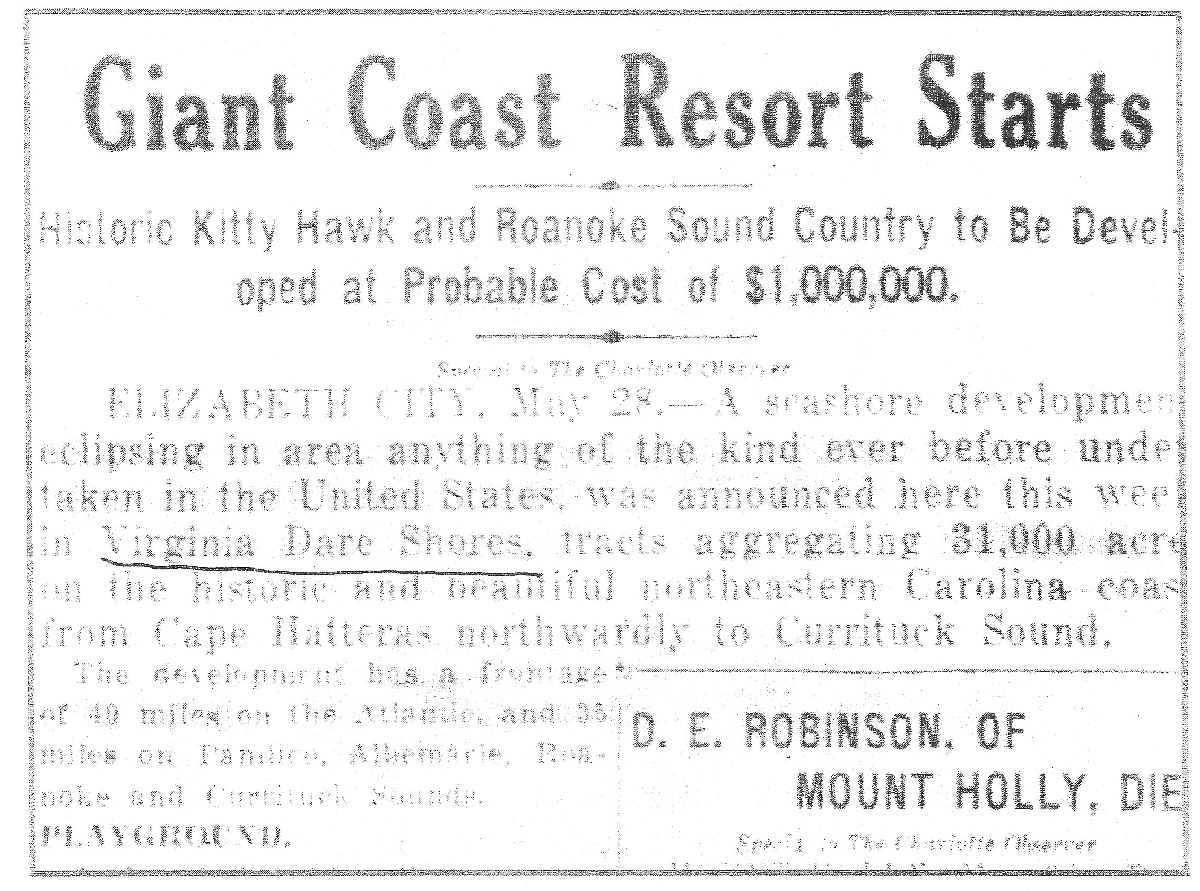

The curmudgeonly editor filled his newspaper with story after story touting Stick and his partners, helping to promote their Virginia Dare Shores project near Kitty Hawk. THRONGS EXPECTED AT VIRGINIA DARE SHORES, a June 3rd headline enthused. Frank Stick was “selling America’s most beautiful coastal playground to Americans,” Saunders wrote in another story.

But W.O. Saunders was no one’s toady. When he felt he was being misled by Stick and his partners, the laudatory stories vanished and he turned on the New Jersey developers.

“THE TRUTH ABOUT THAT VIRGINIA SHORES,” a November 1927 headline thundered. “HOW A PAIR OF ENTHUSIASTIC AMATEURS AND A PAIR OF INDIFFERENT BUSINESS ASSOCIATES PULLED A FLIVVER” (Selling a car in bad condition).

Supporter Spotlight

“In the spring of this year it started out with a great flourish of trumpets, proclaiming a fifty-million-dollar development on the North Carolina Coast in the vicinity of Kill Devil Hills,” Saunders wrote. “It was going to build cement streets on the sand, build hotels, run a great resort and sell lots on Virginia Dare shores faster than deeds could be recorded. AND IT ALL ENDED IN A FIASCO. The lots didn’t sell and the company didn’t pay its bills around town.”

Saunders accused Stick’s longtime associate Allen Hueth of over-promising. He wrote that Elmer Geran, the former congressman, “was losing money and needed to make money.” He called Frank Stick a dreamer who lacked business experience. Capt. Frank Winch, the former publicist, “made a great noise,” Saunders wrote. “But he did not sell lots. He did make a lot of bills … and then he woke up and there wasn’t any more money to pay their bills. NOW THAT WAS A PRETTY HOW DO YOU DO.”

The Saunders story was only the beginning of the troubles at Virginia Dare Shores. The partners were also squabbling. Hueth accused Winch of wasting thousands of dollars on expenses while failing to set up sales offices along the East Coast.

“We do not see how we can go along with [future] financial assistance unless you are willing to follow out our idea,” Hueth wrote in a letter stamped “Confidential.” “As it is now, your company, Shore Properties has had a great deal of money advanced, which we believe should have been spent to much better advantage.” In another letter, Hueth called Winch’s efforts “an absolute failure.”

Winch angrily defended himself, accusing Hueth and Stick of failing to build any actual cottages, let alone a bridge linking the resort to the mainland. “Because of lack of organization and support, because of uncompleted development of the properties itself, because of nasty rumors, because we have permitted our credit to be shattered … these are some of the causes and NONE of them are up to me,” he declared.

There are no records of what happened next, but presumably Winch was fired or quit. For months, Stick and his partners struggled to recover. But progress was slow and they fell behind on payments on their properties. In December 1928, they hosted a gala at their Virginia Dare Shores pavilion celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Wright Brothers’ talismanic first flight. Thousands of politicians, government officials and celebrities arrived by ferry for the festivities. Amelia Earhart rode in the bucket seat of a sedan with Frank Stick’s son, David.

For the moment, all seemed upbeat. But the expected flurry of sales never materialized. Then, following the celebration, tragedy struck. On the ferry ride across Kitty Hawk Bay, Allen Hueth suffered a massive heart attack and died. He had been talking with the region’s young congressman, Lindsay Warren, at the time. Apparently, they had been discussing how to save Virginia Dare Shores.

~

Frank Stick didn’t just lose a fishing buddy and close friend when Hueth died, he lost an important business partner as well. Hueth provided decades of experience in real estate and finance. He was also a critical source of capital. In the succeeding years, Frank struggled to cover options on thousands of acres of Outer Banks property their various companies owned. Some of the lenders began to call the loans and, in some cases, Frank’s shares were offered at tax sales at the county courthouse in Manteo.

According to David Stick, his father emerged from the Great Depression owning a fraction of his original holdings. He lost a half-interest in a large ocean-to-sound tract in Nags Head; a one-third interest in his Colington Island property, and scattered interests along the Lower Banks. I couldn’t confirm this but did stumble across one instance in which Frank arranged for an Elizabeth City businessman to bid on his Kitty Hawk property at tax sale and then transfer the property back to Frank’s Hatteras Holding Corp., in return for an interest in the land. In any case, even as the market for coastal land collapsed, Frank kept enough property to not entirely give up his dream, and continued to advise some of his fellow Asbury Park investors on other land deals.

For years, Frank had been splitting his time between Interlaken and the Outer Banks, where he stayed in hotels. In 1929, he agreed to lease an old lodge called Skyco on Roanoke Island. Frank, Charlotte and David lived there much of the time. Maud commuted back and forth and spent a fair amount of time looking after their parents. Later, Frank built a family home in Kill Devil Hills.

As the Depression deepened, Frank spent most of his time scrambling to keep the family afloat. In the 1930s, he switched from selling lots to building homes. But instead of building traditional Nags Head cottages with wrap-around porches and slanted, overhanging roofs, Frank designed colorful Cape Cod-style beach houses. A row of these cottages along the oceanfront in Kill Devil Hills became known as “Millionaire’s Row.” Later, Frank formed a company, Community Housing Inc., to build low-cost housing in the Tidewater, Virginia, area; lead a work crew clearing a right-of-way for utility lines near Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point; undertook a government-funded restoration of Fort Raleigh on Roanoke Island; and served as executive director of a government commission promoting a seashore park on the Outer Banks – anything to pay the bills.

In public settings, Frank remained calm and confident. However, in Depression-era correspondence with Maud, he let down his guard and allowed his inner doubts to surface. Writing in December 1934, Frank apologized for the family’s financial struggles, blaming himself for his real estate failures and observing that the children shouldn’t have to “suffer” because of his mistakes.” However, Frank rarely ended his letters on a dark note. Hope was always just around the corner, and he often expressed confidence that a big deal he was working on would pan out soon.

In what today feels like a desperate plea, Frank even placed an advertisement in The Independent, declaring: “With faith in the Future — FRANK STICK.”

Next in the series: Inventing the Seashore