Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast.

More than 50 years ago, a beloved high school history teacher named Morgan Harris went in search of the abandoned lumber mill towns of Hyde County.

Supporter Spotlight

Mr. Harris passed away a couple years ago, but I remember him well. He was kind enough to meet with me two or three times when I was writing my book “Along Freedom Road,” which was about the history of the civil rights movement on that part of the North Carolina coast.

He was very helpful to me, and he taught me a great deal about Hyde County’s history.

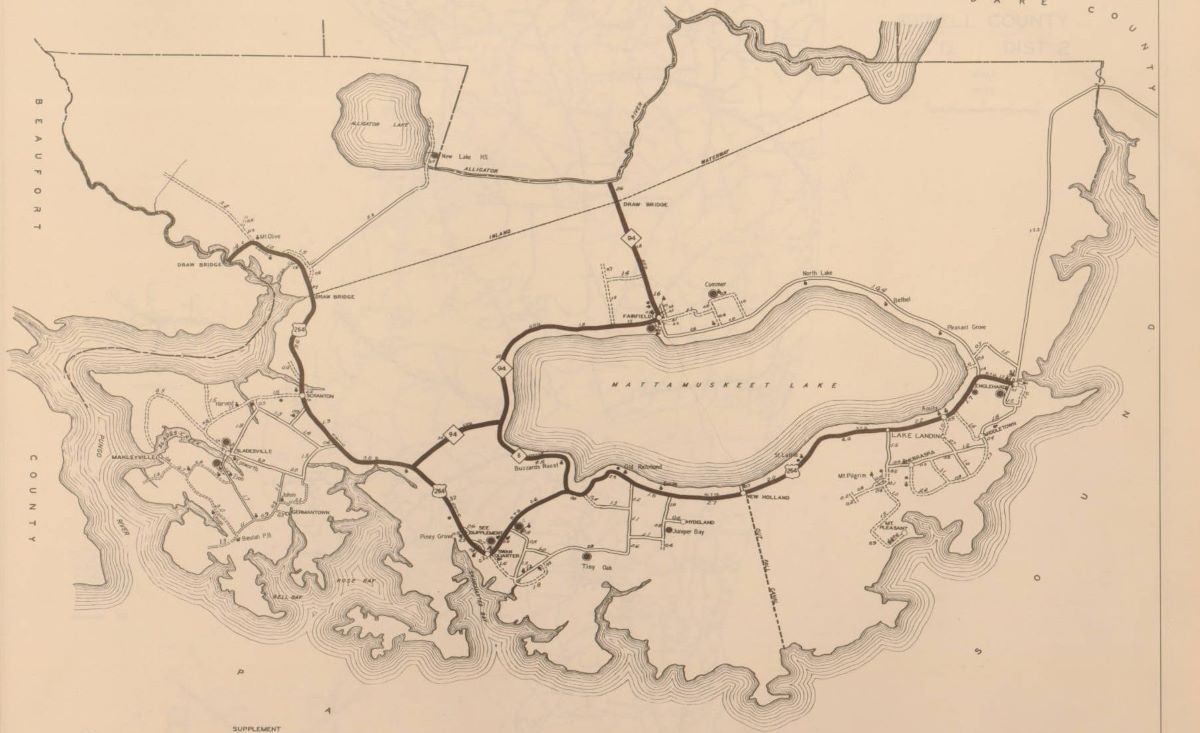

The maps that I am featuring here grew out of his history classes at Mattamuskeet High School. While researching local history, he and his students produced four, hand-drawn maps of lumber mill villages that had been built in Hyde County in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and later disappeared.

Harris knew that other lumber mill boomtowns had also existed in Hyde County. However, he and his students could only find enough information to draw maps of four of them.

He later published those maps in his excellent book, “Hyde Yesterdays: A History of Hyde County.”

Supporter Spotlight

I think those maps are a treasure worth sharing. Every county on the North Carolina coast once had similar lumber mill boomtowns in them, and some quite a few. They are a window into a part of North Carolina’s coastal history that is rarely remembered.

Most of those old lumber mill villages vanished long ago, and now all memory of them is vanishing, too. However, thanks to Morgan Harris and his students, we can at least get a feeling for a few of them.

I am not sure why the mere knowledge of their existence matters so much to me, but it does: I sometimes fear that I am getting a bit like poor Noah, trying to get everybody on the ark before the flood.

As for the rest — the substance of the mill villagers’ lives, their love stories and broken hearts, their struggles for a better life, the songs they sang, the aromas of their camp kitchens and all the other things that really matter in our lives– that is left to our imaginations.

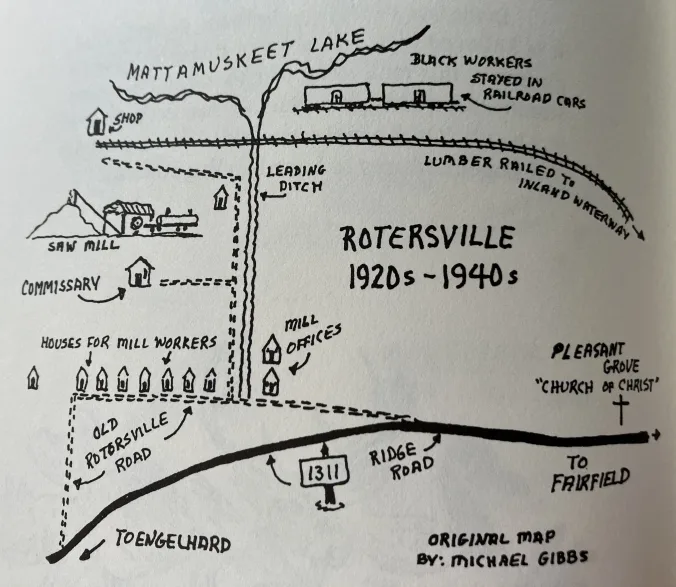

Rotersville: On the Ridge Northeast of Lake Mattamuskeet

This is Morgan Harris’s map of a sawmill boomtown called Rotersville. It was located in a remote community known as Deep Woods, which occupied a sandy ridge on the northeast side of Lake Mattamuskeet. It stood on the edge of what was at that time a great swampy wilderness that reached all the way north to the Alligator River.

Established sometime in the 1920s, the little village included the Rotersville Lumber Co.’s sawmill, a machine shop, commissary, and a cluster of 12 or 14 houses.

According to Harris’s sources, the people of Deep Woods had no other stores in the area, so they often traded at Rotersville’s company’s store even if they did not work for the lumber company.

One old-timer also remembered seeing convict laborers shopping at the company’s store, though he did not say how they came to be there or what currency they might have used.

Morgan Harris’s sources indicated that the railroad on the map was a logging road that led from Rotersville to the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, a distance of about 7.5 miles. The company’s train apparently transported lumber to the waterway, where it was loaded onto barges and shipped north.

Next to Lake Mattamuskeet, the Rotersville Lumber Co.’s black workers bunked down nights in a group of railroad boxcars.

See Roy T. Sawyer’s fascinating article in the spring 2008 issue of Tyrrell Branches for more on the construction of that part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway.

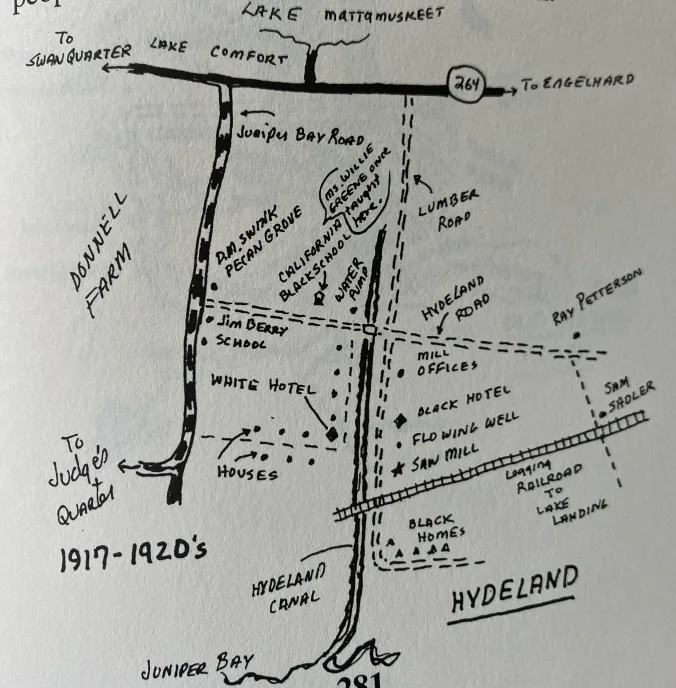

Hydeland: A Village on Juniper Bay

The second of Morgan Harris’s maps gives us a glimpse at a lumber mill boomtown roughly 15 miles southwest of Rotersville, down close to the shores of the Pamlico Sound.

Financed by a pair of wealthy Virginia lumbermen, the Hydeland Lumber Co. built a mill village that came to be known as “Hydeland” south of Lake Mattamuskeet in or about 1917.

The site was located just inland of Juniper Bay, a broad, marshy bay on the Pamlico Sound, 5 miles east of the current state ferry landing in Swan Quarter.

Around the time of the First World War, the Hydeland Lumber Co. accumulated thousands of acres of swamp forest between Juniper Bay and West Bluff Bay.

Evidently, the company also bought at least timber rights to forests — principally cypress, gum and juniper stands, I would think — on the southeast side of Lake Mattamuskeet. In the lower right corner of Harris’s map, we can see that a logging railroad once ran from Lake Landing to the company’s mill in Hydeland.

By 1919, according to Harris, the company’s workers were cutting approximately 52,000 board feet of lumber a day. They had also dredged a canal from Juniper Bay into Hydeland so that barges could carry the company’s lumber south into the Pamlico Sound and then west to the Norfolk & Southern’s railhead in Belhaven.

As you can see on the map, Hydeland had two hotels/boardinghouses, one for whites on the west side of the canal and one for African Americans on the canal’s east side. Will Spencer and his wife “Miss Benie” ran the former; Artie Gaylord, the latter.

Black millworkers and loggers stayed in quarters on the east side of the canal. The company’s white workers stayed in housing on the west side of the canal. Two, one or two-room schools, one for white children, one for black children, were just up the road.

Hydeland was a bustling little town in the early 1920s. Local people recalled that community events — dances, medicine shows, and the like — were often held at the company’s store there.

They recalled that the James Adams Floating Theater even visited Hydeland on at least one occasion.

They also remembered local farmers selling produce to the company’s workers, and the line of local people’s fishing boats that used to tie up at the company’s wharf.

When Morgan Harris explored the former site of Hydeland some years ago, all he could find of its former glory was the canal and the sunken remains of one of the company’s lumber barges.

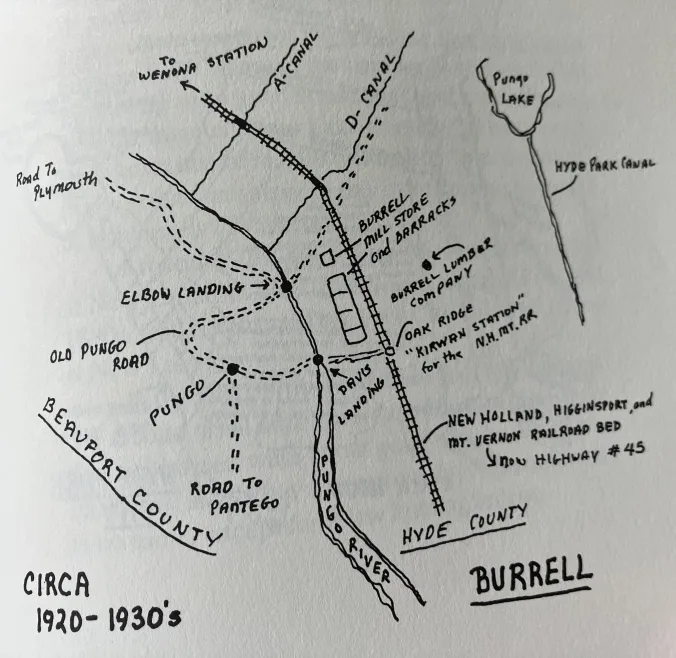

Burrell: In the Headwaters of the Pungo River

This is the third of Morgan Harris’s maps. It shows the lumber mill town of Burrell, which was located in what at that time was still the headwaters of the Pungo River.

The mill village’s location was approximately a mile west of what is now the main entrance to the Pungo Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, in a section of northwest Hyde County known as Grassy Ridge.

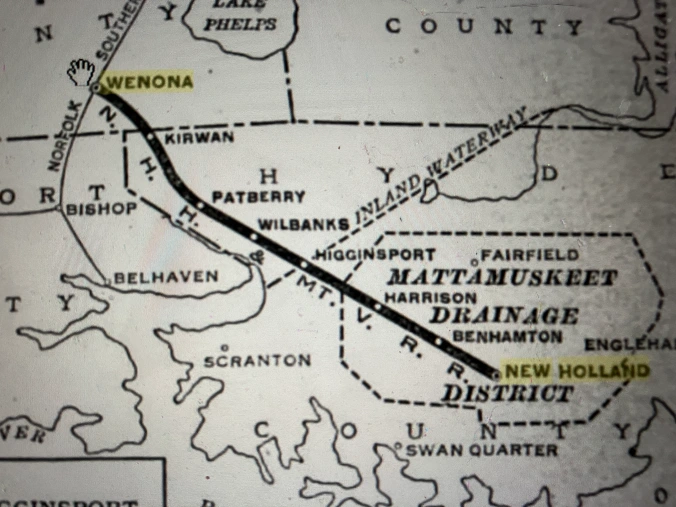

As you can see on Morgan Harris’s map, Burrell was built on the New Holland, Higginsport & Mount Vernon Railroad, a 35-mile-long branch line that ran from Wenona, in southern Washington County, to the pumping station at Lake Mattamuskeet in Hyde County.

The Burrell Lumber Co. heavily logged local swamp forests all the way from Pungo Lake to Alligator Lake, 10 miles to the east. That area included some of the most majestic stands of old-growth Atlantic white cedar (juniper) forest anywhere in the world.

As you can see on the map, Burrell included, besides the company’s mill, a company store, a railroad station, and a large barracks for housing mill workers and loggers.

According to local lore, Davis Landing, shown on the map just below the Burrell mill store and barracks, was the site of an Algonquin village late into the 19th century. The village seemed to vanish with the forest.

To my knowledge, no trace of Burrell has survived to the present day, unless we count the railroad bed. The New Holland, Higginsport & Mount Vernon Railroad is long gone, but the old railroad bed is now the foundation for N.C. Highway 45, at least in that part of Hyde County.

Berkley: A Shanty Town on Scranton Creek

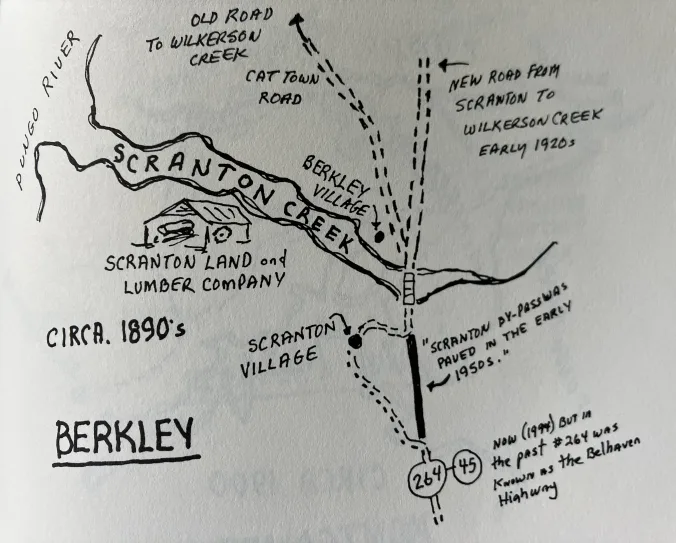

This is the last of Morgan Harris’s maps. It shows the shanty town of Berkley, which was located on Scranton Creek on the east side of the Lower Pungo River, in the southwest corner of Hyde County.

When Harris visited with them, local old-timers remembered Berkley as a hard-drinking, hard-living place and as a refuge for drifters and the dispossessed.

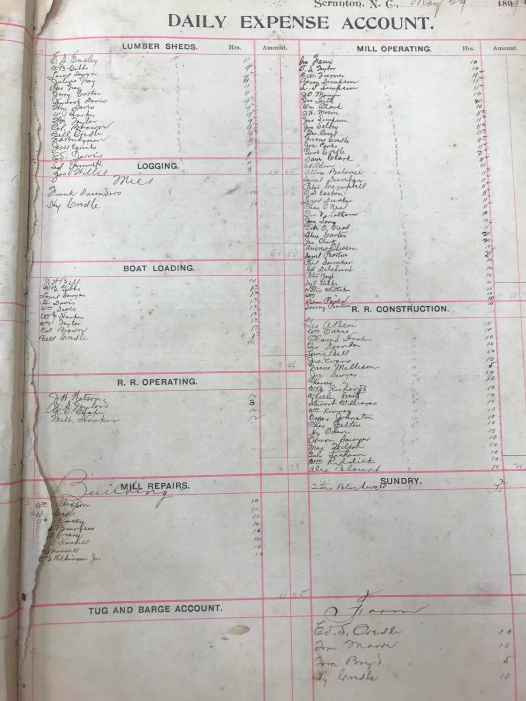

The inhabitants of Berkley, the men at least, worked for the Scranton Land and Lumber Co., which had been chartered in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1889. According to news reports at the time, the company’s holdings in Hyde County exceeded 100,000 acres of woodlands on that east side of the Pungo River. (Scranton Republican, Sept. 16, 1892)

Most of the company’s workers were African American. As we can see on the map, their little settlement grew up around what is now called the Cat Town Road, just across Scranton Creek from the Scranton Land and Lumber Co.’s mill.

According to Morgan Harris’s sources, Berkley burnt to the ground after a not especially sober customer at one of the settlement’s liquor houses accidentally started a fire that got out of control.

Makleyville: A Village on Slade Creek

Another lumber mill village, Makleyville, which was mentioned but not mapped by Morgan Harris, was located at the mouth of Slade Creek, a lovely stream that flows into the Pungo River five miles south of Belhaven. A wealthy Edenton merchant named Metrah Makely first established a sawmill there in the 1880s.

(Metrah Makely was the little community’s namesake, but I always see its name spelled slightly different: Makleyville.)

By 1891-92, however, Makleyville and its sawmill were purchased by the Scranton Land and Lumber Co.

The Makleyville Hotel was the village’s center. In addition to providing rooms for visitors, the hotel served as the Makleyville’s post office and company store.

According to a 1949 article in the Belhaven Times written by Ethel Ayers Gibbs, the daughter of the hotel’s former managers, the hotel also served as a boardinghouse.

In that article, Ms. Gibbs recalled that “drummers, as traveling salesmen were called in those days, came by boat to Makleyville.” The drummers stayed in the hotel and, she recalled, two local men, W. J. Harris of Swan Quarter and Will Harris of Leechville, carried them and their wares around that part of Hyde County.

The village of Makleyville included sawmills, dry kilns, living quarters for the workers, a pair of warehouses, and a long wharf that reached into the Pungo River. Most of the buildings were built over the water, boosted up by sawdust and pilings.

In her article in the Belhaven Times, Ms. Gibbs recalled that “Makleyville at its peak had around 200 population and men from outlaying farms [also] worked at odd times at the mill.”

She noted that she had “seen as many as six and eight big barges from Baltimore up at the mill loading at one time.”

Wharf Pilings and Sawdust

Everything — towns, railroads, shipping traffic, and the old-growth forests themselves — seemed to come and go quickly during the lumber industry’s heyday on the North Carolina coast.

The fate of those lumber mill villages on the east side of the Lower Pungo River was typical.

The Scranton Lumber and Land Co. sold its holdings in Hyde County in 1895, evidently after the last of the most profitable timber — the old-growth cypress, gum and juniper — had been cut. A new company, the Allegheny Lumber Co., also out of Pennsylvania, took over the operation, but itself sold out to the John L. Roper Lumber Co. sometime between 1902 and 1905.

The Roper Lumber Co. was one of the largest lumber companies in the American South. However, by 1905, its managers saw little profit in the largely deforested glades on that side of the Pungo River. Instead, the company took the bleak cutover lands that were left and began to sell them in smaller parcels.

Most were either cleared, drained, and turned into farmland or, down the road, into pine plantations.

The lumber mill on Scranton Creek shut down. About 14 or 15 miles farther down the Pungo, the company’s mill at the mouth of Slade Creek closed as well, sealing Makleyville’s fate.

The Makleyville Hotel hung on awhile, but eventually shuts its doors, too. Workers drifted away. Drummers stopped coming. Lumber barges from Baltimore were no longer seen on Slade Creek. I have not seen them myself, but I have heard that heaps of sawdust and the pilings of the mill village’s old wharf are all that is left of Makleyville.

***

Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.