We’re all familiar with the image: the lone, white fisherman donning a yellow slicker.

Think Gorton’s Seafood, “Trusted since 1849.” You know the one.

Supporter Spotlight

“For some reason, that image is so etched in people’s minds, but what that hides is a lot of diversity in this fishery, in any fishery, particularly when you get to the processing sector, the packing, the trucking, the retail markets and then, of course, cooking,” said Barbara Garrity-Blake, Duke University Marine Lab cultural anthropologist and president of NC Catch. “But there are also African Americans who are commercial fishermen, who are charter boat captains. There’s more than meets the eye.”

NC Catch, a nonprofit aimed at educating consumers about the importance of buying local seafood, is spearheading a collaboration of Black seafood business owners and historians to roll out the North Carolina Black Seafood Trail.

The traveling exhibit will share the under-told, multifaceted, sea-to-table story of Black North Carolinians’ contributions to the state’s fisheries.

The conceptualization of the historic trail goes back a couple of years when conversations within NC Catch, an organization that includes Black chef ambassadors and seafood market owners, began reflecting on Black-owned seafood businesses.

Personal experiences and stories from those who’ve lived it highlighted just how much fishing — from catching fish to cooking it and eating it — is intricately woven into the cultural fabric of Black communities.

John Mallette recalled his childhood days when, invariably every late September through October, families would converge at the Ocean City Fishing Pier in a “statewide pilgrimage to the beach.”

Supporter Spotlight

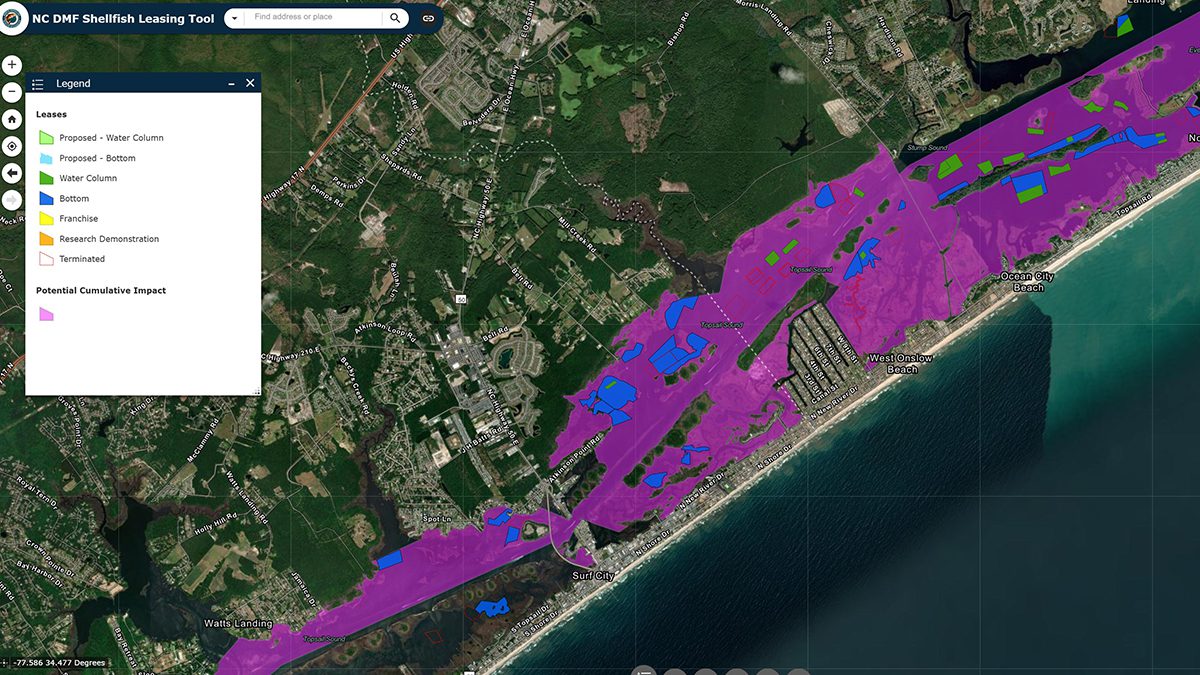

Before the pier met its demise following Hurricanes Bertha and Fran, both of which pummeled Topsail Island in 1996, it was a prime location for spot and sea mullet fishing.

The yield people caught at Ocean City, a milelong stretch of land in North Topsail Beach believed to be one of the first beachfront communities owned by African Americans, meant months’ worth of fish in the freezer.

Cars and trucks too late to get a spot in the pier parking lot lined the sides of N.C. Highway 210. The local motel would have to hang its “no vacancy” sign. Pickup trucks with campers would be parked off the shoulders of the street on which Mallette’s family lived. He remembers how people would sleep in shifts to ensure someone always had a fishing pole in hand.

“It would be so full, the fire department would have to stop people,” Mallette said.

The influence of those experiences obviously ran deep. Mallette has been a commercial fisherman, he’s a for-hire recreational charter captain, and he’s co-owner of Southern Breeze Seafood in Jacksonville.

He was demonstrating how to cut fish at the North Carolina Seafood Festival in Morehead City last year when Garrity-Blake introduced herself.

She was excited to meet him and pitch the idea of lifting up the stories, recognizing and celebrating the contributions of African Americans to both the seafood industry and fisheries.

“He has so much knowledge about not only what’s going on now, but the history of the sort of cultural coastal traditions of Black communities,” Garrity-Blake said.

Mallette happily accepted the invitation to co-manage the project.

“There’s a lot of different angles to this,” he said. “It’s not as straightforward as just the commercial fishing industry. There’s a lot of things people just don’t understand. There’s so much that people don’t know and there’s a lot of stereotypes that were passed down generation after generation that, unfortunately, push African Americans away.”

Like the stereotype that Black people can’t swim, he said, that’s led to a cycle of African Americans working in the fish houses but not on the boats.

That hasn’t always been the case.

The menhaden fishery was at one time the largest employer of Black people in the mid-Atlantic.

“There was a fish factory in Beaufort and almost everybody in that factory was Black and the majority of the crew members on the vessels were Black,” Garrity-Blake said.

One might argue menhaden, an oily, boney fish harvested for use as animal feed, bait for fisheries and fertilizers, is not really seafood since it’s not sold in a market as such, she said.

But menhaden boat crew members and factory workers carried forth a long tradition of bringing home menhaden roe, perhaps better known as poor man’s caviar.

“Some of the people in North River, to this day, talk about how the fishermen used to bring home menhaden roe and that was just considered a real coveted food, not just among the Black communities, and people around here in Carteret County and Down East just love menhaden roe and you just can’t get it anymore,” she said. “That was part of the local food that people really loved and there’s lots of stories like that.”

Mallette said the N.C. Black Seafood Trail will not only show North Carolinians how African Americans contribute to fisheries, but also be an opportunity to educate African Americans about the importance of eating North Carolina seafood, questions to ask at their local seafood markets, and offer alternative ways to prepare seafood outside of the more traditional method of frying.

“The older generation is dying off. You have a younger generation that knows about what sustainability is,” he said. “They don’t know to ask the questions. They’re not educated on seafood. Once you educate them, that’s how you make a big improvement on the quality of North Carolina seafood as a whole. It starts with education and goes from there.”

NC Catch received a $20,447 Community Collaborative Research Grant, a program supported by North Carolina Sea Grant and the North Carolina Water Resources Research Institute in partnership with North Carolina State University’s William R. Kenan Jr. Institute of Engineering, Technology and Science.

Working with NC Catch chef ambassadors and the nonprofits regional network, which extends from the Outer Banks south to Brunswick County, Garrity-Blake and Mallette are compiling a list of people to contact and interview.

Those interviews will be paired with photography and videography to create an oral history for the traveling exhibit.

The research will be stored in the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island. The museum plans to open an in-house exhibit of the project.

“What I would really like to see is more African Americans being involved in the seafood industry on all levels whether it’s coming down to the beach to fish or buy fish directly off a boat,” Mallette said. “I would love to see more African Americans learn to eat better seafood, eat cleaner seafood. I think starting to see more of that is what would be something I would really love to see come out of this project. This project is the key to that door that we haven’t been able to open.”