You may have noticed that the sneezing, runny nose and itchy, watery eyes that come with seasonal allergies are beginning earlier in the year.

That’s because climate change is making allergy season longer and worse for the 26% of adults and 19% of children in the U.S. that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says suffer from seasonal allergies, a new study finds.

Supporter Spotlight

Climate Central, a policy-neutral nonprofit of scientists and communicators who research and report on the changing climate, released Wednesday the report, “Seasonal Allergies: Pollen and Mold” that states, “A growing body of research shows that warming temperatures, shifting seasonal patterns, and more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere –all linked to climate change and greenhouse gas emissions — are affecting the length and intensity of allergy season in the U.S.”

Climate Central Meteorologist Lauren Casey explained to Coastal Review Tuesday that as a thickening blanket of carbon dioxide, or CO2, in the atmosphere traps heat and warms the planet, winters are shortening and there are longer growing seasons. This leads to allergen-producing plants pollinating both earlier and later in the year.

“So, allergy sufferers feel the effects for weeks or even months longer than they did before,” she said. “But as CO2 concentrations rise, many plants respond by producing more pollen, and pollen with higher concentrations of chemical compounds that trigger allergic reactions. So, it’s not just higher temperatures and shorter winters that make allergy season worse.”

Essentially, the warmer temperatures increase the length of the growing season, which begins with the last freeze of spring and ends the first freeze of fall, leading to plants releasing more allergy-inducing irritants like pollen and mold spores for a longer period of time.

The report also found that there’s a connection between thunderstorms and increased asthma.

Supporter Spotlight

“A number of studies have shown associations between thunderstorms and asthma attacks or asthma-related hospitalizations — a phenomenon known as ‘thunderstorm asthma’,” according to the report.

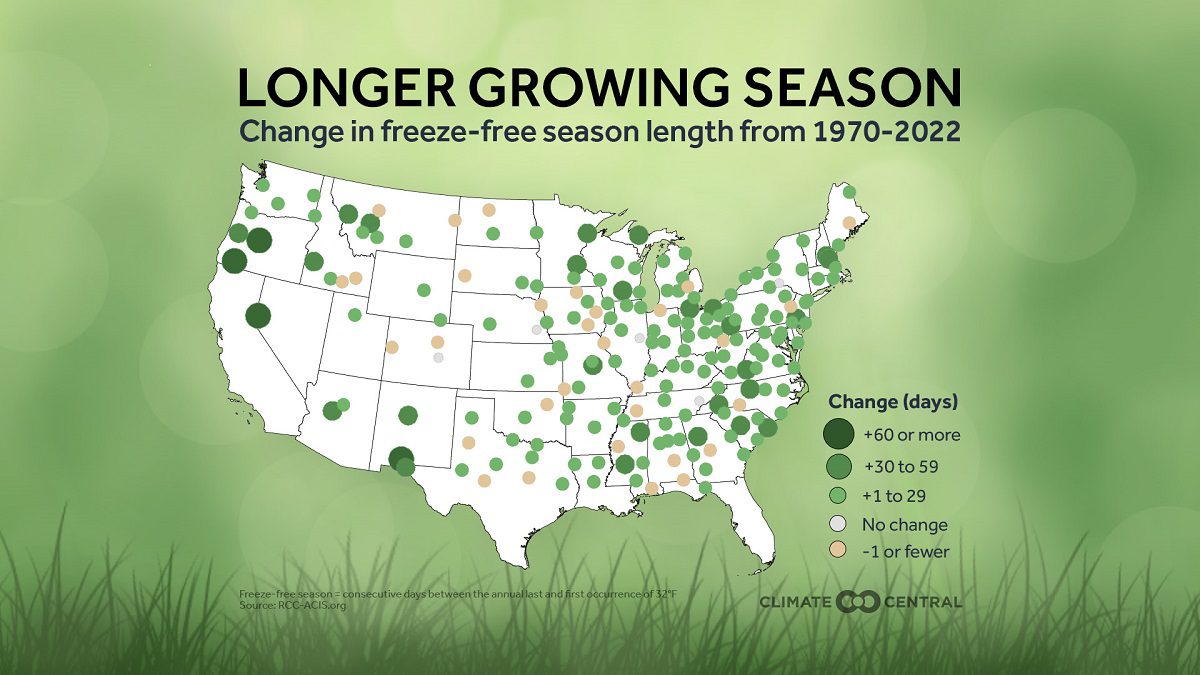

For the study, Climate Central scientists looked at temperature data since 1970 for 203 U.S. cities. They found that the freeze-free season is lengthening across the country, giving plants 15 days longer on average to grow, flower and release pollen.

Of the cities analyzed, 85%, or 172, saw their freeze-free seasons lengthen during the study period, including four of the five studied in North Carolina: Asheville by 33 days, Greenville by 25 days, Raleigh by 29 days, and Wilmington by six. Charlotte’s season shortened by nine days.

Since 1970, the freeze-free season lengthened the most in the West to 27 days among the stations analyzed. The season lengthened in the Southeast by 16 days, the Northeast to 15 days, and in the South to 14 days. The Central region saw the freeze-free season lengthen by 13 days.

Casey said that in the Southeast, depending on what triggers their allergies, many are experiencing an extra month of allergy season compared to the 1970s, such as Greenville and Raleigh residents.

“That means allergy symptoms, which can heighten the risks of asthma attacks, can appear earlier than they used to, catching people by surprise,” Casey said.

With the association between thunderstorms and asthma attacks or asthma-related hospitalizations, while the science behind the connection isn’t fully understood, research shows that pollen and mold spores are playing a part.

“Thunderstorms bring pressure changes and winds that blow around pollen and mold spores — breaking them into smaller, more easily inhaled particles and transporting them through the air. Studies have shown high pollen and mold counts around thunderstorms correlate with increased asthma symptoms and hospital admissions,” according to the study.

“Because researchers are still learning about this meteorological health risk, it’s difficult to predict who might be affected or where another thunderstorm asthma event might occur. There is enough evidence for some health professionals and researchers to caution people with asthma or seasonal allergies to be alert for symptoms when thunderstorms are approaching,” the study continues.

Casey said that Climate Central pursued the study because climate research has documented the change in growing seasons, which affects many pollen producers, “thus it made sense to look into what longer seasons meant for allergy sufferers.”

Regarding the results of the study, Casey said “the longer and more intense pollen seasons weren’t a surprise, and neither was the role that molds play in allergy season, even outside conventional growing seasons. But we didn’t expect to find as much documentation of the connection between allergens, thunderstorms, and asthma risk. Particularly in the East, where thunderstorm potential is rising, the link to allergy-related asthma reactions might surprise people.”

She added that rain can be a double-edged sword when it comes to pollen and mold.

“It does serve to cleanse the atmosphere initially, however rain also causes the pollen grains and mold spores to break into tinier bits – more likely to be airborne once dry and reduced to a size that can easily enter the nose and sinuses,” she said.

Managing allergies can be expensive and can have significant health impacts, such as triggering or worsening asthma. The report notes in the U.S. that the total cost of allergies is more than $18 billion a year. During 2008-2013, the annual medical cost of asthma was just over $3,200 per person. Additionally, one study suggests that pollen exposure can increase susceptibility to respiratory viral infections, including COVID-19.

“And the health effects from allergies and asthma can be compounded by other environmental pollutants linked to our warming climate, including ozone and diesel fuel pollution,” the study states.

To help avoid the worst impacts, Casey recommended those with allergies purchase quality air filters and limit their time outside during seasonal peaks. “But of course, reducing CO2 emissions is the only long-term way to limit the warming and seasonal changes we’re experiencing.”

Before joining Climate Central, Casey was a broadcast meteorologist for more than 15 years, most recently at the CBS station in Philadelphia, when she said she collaborated with Climate Central on several climate-related stories. She has also been working toward her master’s with much of her coursework centered around climate change, “this in combination with Climate Central’s powerful mission inspired my transition to the organization last spring.”