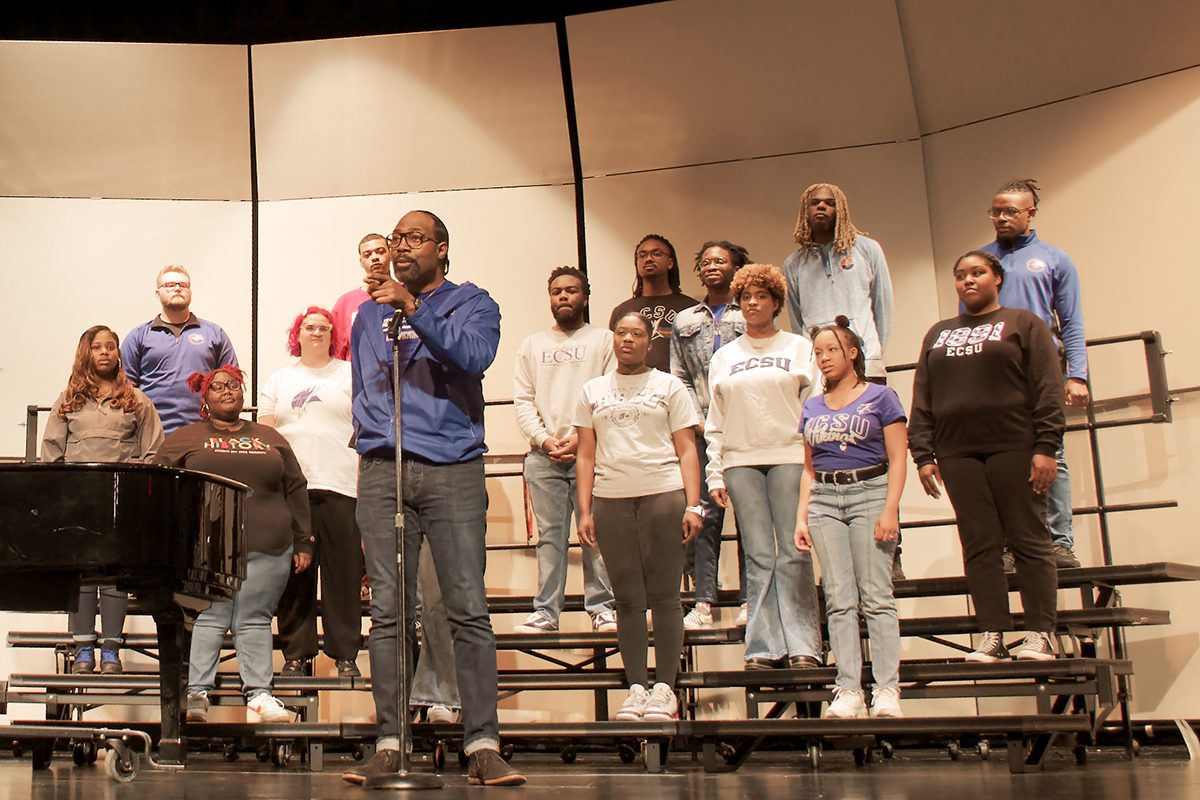

The Elizabeth City State University Choir recently lifted their voices in song during a performance honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday in the First Flight High School auditorium in Kill Devil Hills.

The trip to Kill Devil Hills Jan. 14 was not a long one, an hour at the most, but it was in keeping with the choir’s long tradition of traveling to perform for as many eager audiences as possible.

Supporter Spotlight

It is a tradition that dates to the choir’s founding in 1933 by Dr. Evelyn Adelaide Johnson. In her book, “History of Elizabeth City State University: A Story of Survival,” published in 1980, she wrote about the choir’s custom of traveling to perform.

“There are few churches in the area, black and white, in which the choir has not appeared … The choir has sung for local clubs, societies, fraternal organizations, banks, the navy, general assembly celebrations, and for other groups in other states,” she wrote.

More recently, Dr. Walter Swan, director of choral activities for ECSU, described an upcoming spring tour.

“We do take annual tours since we’re now back from COVID and we’re able to travel,” he said. “This year’s tour will take us as far south as South Carolina, potentially Georgia and will take us up to D.C.”

It may seem remarkable that through wars, the Great Depression and civil rights turmoil, a choir from a relatively small, historically Black university in a small city in northeastern North Carolina would be able to continue to tour and perform.

Supporter Spotlight

Perhaps more remarkably, though, in the 90 years since Dr. Johnson came to the school, there have only been three choral directors.

When Johnson arrived on campus in 1933, ECSU was still a State Normal School with a two-year course of instruction. It would not become Elizabeth City State Teachers College until 1939 when it was able to award its first baccalaureate degrees in elementary education.

“Many students who entered the school between 1934 and 1939 were almost poverty stricken,” Dr. Johnson wrote. “They entered sometimes with less than five dollars, brought their few belongings in a burlap bag or some other nondescript luggage.”

Teachers, she mentioned, were on half-salary.

“It took ten years to recover salaries in vogue during the 20s, before the depression,” she noted.

In her book, she lists the regular events that she scheduled for her choir, community Christmas carols at the homes of respected Black and white citizens, a choir scholarship fund and annual choir tours during the school year.

She retired in 1975, and Clarence Lewis, who sang in the choir for two years in the early 1970s, recalled clearly what it was like.

“It was an experience. And if you didn’t know how to read music, you couldn’t be in a choir,” he said.

At the time Lewis was fresh out of the military and spent two years at ECSU. Then, in his words, “I … made the decision that I wasn’t ready for college. I went back into the military,” where he spent 21 years, retiring as a master sergeant.

The two years he was at ECSU included giving performances across the country and internationally.

“We sang in quite a few places in the United States. Major cities like New York and Delaware and places like that. Okay, so we also toured overseas in Belgium,” he said.

ECSU is a tradition in many families and Lewis’ daughter Michelle sang in the choir when she went to college. Billy Hines was her choral director and like Dr. Lewis, he demanded his choir know their music.

“If you loved to sing, and you had some ability, professor Hines was willing to work with you. But you had to put in the same time that everybody else did,” she said.

Everyone was expected to know their part, she added.

“If someone was singing off-pitch in a section, if he couldn’t tell who it was right away, everybody had to stand up and sing the part a capella, one by one,” she said. “There was this one time where I didn’t know the part. It was me and I knew it was me … I kind of hoped I’d figure it out before he got down the line to me … it was my turn … and I couldn’t sing it.”

Not being able to sing the part seems to have left an indelible memory.

“I can still sing it to this day,” she said.

Attention to detail and knowing how to perform to the highest standards are things that ECSU graduate Tshombe Selby, who is now performing with the Metropolitan Opera of New York, remembered.

“I would not be where I am without Mr. Hines and the ECSU choir … Mr Hines’ attention to the music and acceptance of nothing less than your best are the teachings that are my foundation in classical music and my performance career. He was more than an instructor, he was Mr. Hines,” Selby wrote when asked about Hines.

Swan has been the choral director since Hines retired in 2009 after 34 years. He was already teaching vocal performance at ECSU when, as he describes it, “I was ushered in.”

Other traditions that were established in 1933 continue. The choir is made up of music lovers, but they do not have to be music majors.

“We do have good musicians, but because we’re not solely music majors, we are taking people who are music lovers who come from other choral programs from high school,” Swan said.

Like Johnson and Hines before him, he sees his role as more than an instructor of music, and is especially aware of the importance of ECSU as an historically Black college and university.

“I think (there is) pride that comes with HBCUs, especially being a product or coming through that rake of being a graduate of Alcorn State University. I understood the importance of this particular lay of the land from Mississippi. Also being educators and knowing that there is a greater purpose beyond self,” he said.

Yet if he is aware of the traditions that have been created over 90 years, he sees that as a path forward for the school and choir, and not something that will slow the path to the future.

“I don’t have large shoes to fill, I have to only walk in my own, create my own footprint,” he said. “You don’t ever leave something like you found it. Always try to leave it better. I think that’s what Evelyn did, and that was trying to create something better. What Billy did was to capitalize on Evelyn and (what I’m) doing is to capitalize on Billy.”