RODANTHE — A new bridge has bypassed a dangerous and persistent ocean overwash problem on the roadway on the north end of Hatteras Island. Now residents of this tiny village are looking for beach nourishment to protect their homes from washing into the ocean.

The reason that Rodanthe is at risk is the same reason that a shoreline protection project would be very difficult: the unmanageable forces of geology, erosion and sea level rise.

Supporter Spotlight

“Look at the shape of the coast from Rodanthe down to Waves and Salvo, a broad convex to the shoreline,” Tim Kana, owner of Columbia, South Carolina-based Coastal Science & Engineering and a professional geologist, explained to Coastal Review. “You’re eroding at Rodanthe and accreting at Waves and Salvo. This crescent moon is just shifting down the coast.”

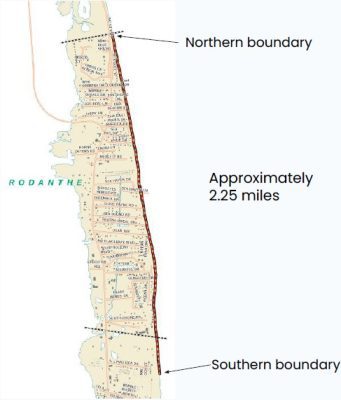

Averaging 14 feet per year and as much as 20 feet at times in some sections of beach, Rodanthe has one of the highest erosion rates on the East Coast, and in recent years it’s been accelerating. Homes that had many yards of beach out front when purchased are now sitting at the edge of the surf. Last year, three of them collapsed into the sea, and others now must be relocated back from the shoreline to prevent the same fate.

Special Report: Houses on the Edge

Without an infusion of lots of state or federal money, or enormous amounts of local tax revenue, the prospect of a new shoreline protection project for privately owned properties would be impossible.

At a standing-room-only community meeting held by Dare County Jan. 18 in Rodanthe, county manager Bobby Outten told residents that the first step in looking at beach nourishment is getting an update on the erosion rate provided in a 2013 study done by Kana’s firm that estimated a $20 million cost to widen Rodanthe’s beaches.

Supporter Spotlight

“We know that’s not going to be enough,” he said.

In a slide presentation, Outten gave an overview of beach nourishment projects in the county, starting with Nags Head in 2011. After the federal government declined to fund a planned project, the county stepped in and paid half the costs out of a special fund it created with 2% of its annual occupancy tax revenue. Since then, the county has continued sharing costs with numerous other town projects in the county, as well as its own in the unincorporated villages of Avon and Buxton.

Today, there is about $6 million available in the fund, he said, and to fund just the prior $20 million estimate for Rodanthe nourishment, the county would need $30 million.

“The question is, ‘how are we going to pay for this?’” he said. “That fund is not going to grow fast enough.”

The tax value generated from the combined 81 or so properties in Rodanthe would also fall woefully short.

Outten added that Dare County and other coastal communities in North Carolina have been asking the state to establish a recurring fund to help pay for nourishment projects.

“I’ll tell you, it’s not just us,” he said. “We’re all working all angles we can.”

In Dare County alone, two other areas — the “canal zone” on N.C. Highway 12 south of the Basnight Bridge and the Isabel Inlet area on N.C. 12 in Buxton — are subject to severe erosion. But those areas are part of a critical public transportation route. Rodanthe’s oceanfront area, on the other hand, is unlikely to be eligible for public funds because, although the beaches are part of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, the affected property is mostly vacation homes that are privately owned.

During the public comment period, Jett Ferebee, who owns a campground in Rodanthe, said that because the National Park Service owns the public beach, the situation is different than the other areas of the county.

“If we lose the entire beach in Rodanthe, I would declare that’s an impairment of the our National Park system,” he said. “Rodanthe, we’re sitting here, an unincorporated village, we really don’t have much representation. We need some federal help.”

Dave Hallac, superintendent of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, said that National Park Service policy does not permit spending public funds to protect private property. Not only are hundreds of parks competing for slim funds, there are numerous park needs and projects on the Outer Banks, including severe erosion on Ocracoke Island, that is threatening the National Seashore and N.C. 12.

Dare County, one of the most popular tourist destinations in the state, is not a poor or underserved county, so it does not qualify for government funds that are intended to help less wealthy populations and communities. That was part of the reason that Rodanthe was largely unsuited for a recent state grant program to buy out at-risk homes, Outten said.

Outten said he is trying to see what the options are, and the first step is finding out what the current erosion rate is and how much cubic yardage of sand would be required to do a nourishment project. The $35,000 update, which would provide a “rough estimate” of the extent of the project, would likely take 90-120 days to complete.

Kana, who said that work had not yet begun, explained that Rodanthe is not only challenging because of the high erosion rate, but also because it doesn’t have much naturally deposited sand available near shore, so it would have to be found farther offshore.

But it’s hard to know what to expect before doing the updated engineering work.

“Rodanthe is more exposed with the curvature of the shoreline right there,” Kana said. “The only way you can address that is with sand-retaining structures.”

But those structures are not permitted on ocean shorelines in North Carolina.

With so much erosion and storm damage happening nationwide, finding enough public money is at best extremely competitive.

“What I heard from that meeting is that new beach nourishment in Dare County is basically dead,” said Rob Young, director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University. “It was a very straightforward presentation.”

Young said he appreciated Outten’s frankness with Rodanthe residents about the situation. “That’s certainly not what they wanted to hear,” Young said.

Young, who attended the meeting, said he was disappointed to not hear a discussion of future buyouts. “What threatens the beach is development,” he said. “It’s not the park service’s job to hold the beach because there’s development there.”

Young said that with enough money, beach nourishment could buy time in Rodanthe to establish a buyout program, he said.

“It’s the best long-term solution,” he said of buyouts.