Part of a history series examining each of North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties.

The earliest permanent settlement of North Carolina by Europeans occurred north of the Albemarle Sound. But increased migration and the desire for land soon pushed those settlers outside of this limited area.

Supporter Spotlight

The men and women who moved south of the Sound found a swampy, inhospitable region. Their perseverance helped create Washington County, at one time a prosperous county that gave the state several of its most famous leaders.

The story of Washington County is one of isolation, success and an eventual renewal on the banks of the Roanoke River.

Following the earliest settlement of the Albemarle region in the late 17th century, English immigrants to North Carolina craved more arable land for tobacco cultivation. While some went west, others moved south across the Albemarle Sound.

Early North Carolinians also secured land grants on several of the area’s major rivers. One of these was the Roanoke River, which starts in Virginia and enters North Carolina near present-day Roanoke Rapids. The community that later became Plymouth, located on a bend of the Roanoke River, was first settled in 1727, according to the North Carolina Gazetteer. Other communities like Roper and Mackeys grew up around the county’s creeks and on the sound.

The area south of the Albemarle Sound remained sparsely populated for several decades. Over time, an increase in population led to the need for more counties. In 1729, the section of North Carolina north of former Bath County and south of Albemarle Sound became Tyrrell County. In 1799, Tyrrell County’s westernmost section became Washington County, named for George Washington.

Supporter Spotlight

According to “The formation of the North Carolina counties, 1663-1943” by David Leroy Corbitt, the eastern boundary was a line “beginning at Bull-point … to the centre of the Indian swamp, where the road crosses … [extending] to the west end of lake Phelps… to [the] Hyde county line.” An 1801 annex gave Washington County all of what was then known as Indian Swamp.

In the antebellum period, Washington County was defined by some of the largest plantations in North Carolina. The Roanoke River and Albemarle Sound were ample sources of transportation. Tobacco and corn were planted in the rich soil of river-adjacent districts. The county also had communications with the northern side of Albemarle Sound by way of Mackey’s Ferry. The ferry operated for more than 200 years and was a key link between the older communities north of the Albemarle and the growing regions to the south and west.

The most prized plantation in the county was Somerset Place, which was founded by a group led by Josiah Collins on Lake Phelps in the 1780s. According to the plantation’s National Register of Historic Places nomination, Collins was a political leader in the state who acquired a massive amount of land, built mills, and introduced agricultural methods new to North Carolina such as rice cultivation. A nearby plantation owner, James Johnston Pettigrew, became a famed Confederate general that was killed at Gettysburg.

As in the rest of the state, slave labor was prevalent. Over 40% of the county’s population was enslaved, according to the Hergesheimer map of 1860. Somerset Place has become noteworthy not only as a center for antebellum wealth but also a site of memory for the hundreds of enslaved African Americans who lived there in the 19th century.

In the 1980s, historian Dorothy Spruill Redford traced the lives of many of these families and helped organized a reunion of around 1,500 descendants of slaves and their owners. The reunion garnered national attention and a number of prominent visitors, including the North Carolina governor and “Roots” author Alex Haley, according to the New York Times.

In his introduction to Redford’s “Somerset Homecoming,” Haley wrote that when he learned of the project, “I was thrilled — thrilled not just at what was happening there that day, but for the connections that such a gathering of families spoke of — for the thread that ran back through the generations and will most surely run ahead into the future.” Redford’s work transformed the interpretation of slavery at Somerset Place and other plantations throughout the South.

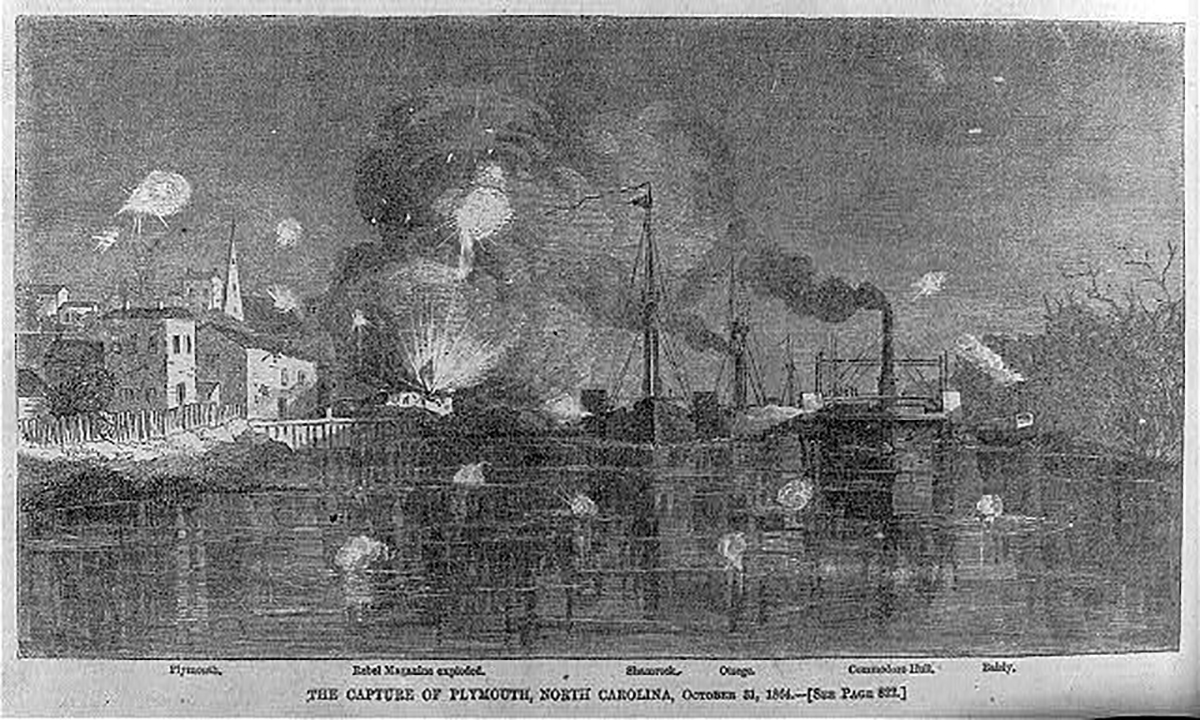

During the Civil War, Plymouth played an important role in an often-ignored campaign late in the conflict. In 1864, the Confederacy attempted to take back eastern North Carolina from the Union. Confederate Gen. Robert F. Hoke, along with the ironclad ram Albemarle, launched an exceptional raid that defeated Union leaders Henry W. Wessells and Charles W. Flusser and led to Confederate control of Plymouth.

The victory was short-lived, for Hoke was recalled back to Virginia a few months later and the Union reoccupied the town for the remainder of the war. Research has shown that the Confederates were also responsible for war crimes against African Americans after recapturing the area.

Following the war, Washington County embarked on an economic project like those of surrounding counties in eastern North Carolina. Much of the county remained agricultural. Tenant farming replaced the plantation system, and some farmers moved from tobacco and corn to peanut and truck farming. But in some areas, industry began to take a hold.

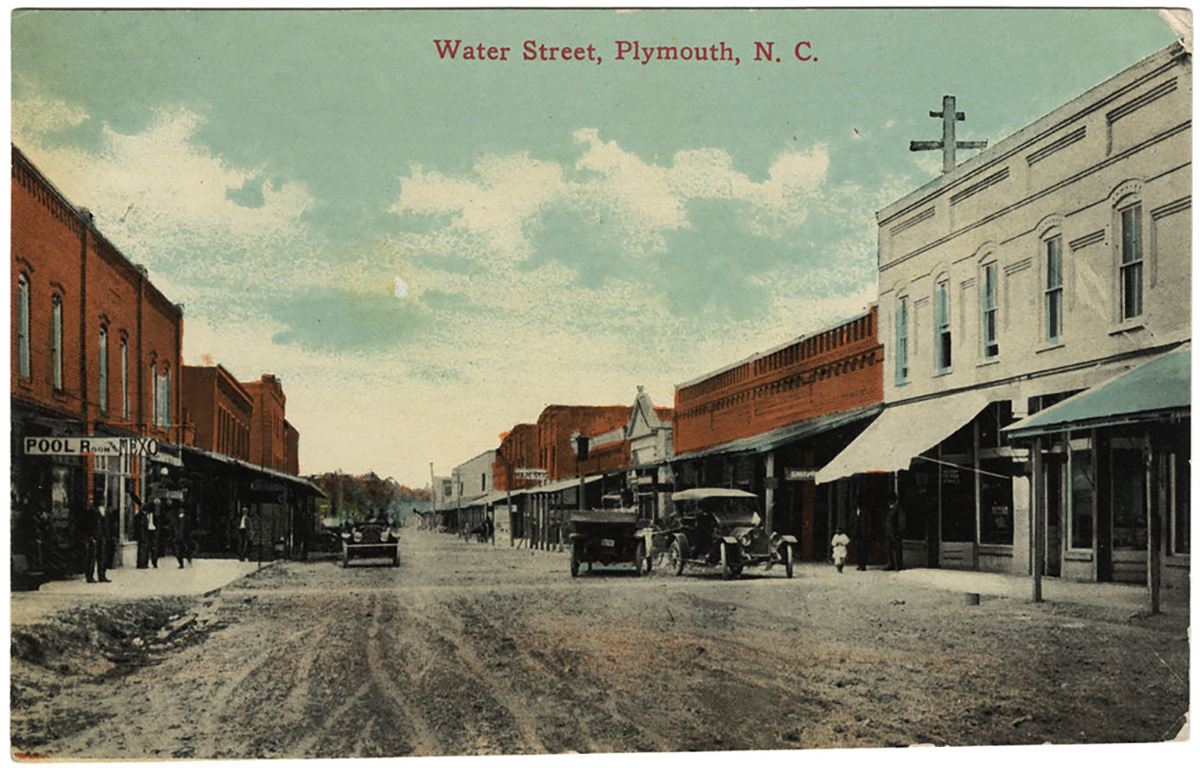

This industry centered on Plymouth, where the population doubled between 1900 and 1910. Plymouth became a center for the manufacture of wooden handles, lumber, and paper. Industrial prosperity led to the construction of the neoclassical Washington County Courthouse in 1919.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, numerous notables called Washington County home. These included stage director Augustin Daly, author and activist Don Brown, and NFL linebacker Charles Bowser.

Comedian J.B. Smoove, known for his work on HBO’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” was born in Plymouth and often visited his maternal relatives there.

These famous residents did not lead to prosperity in the county, however. Following the decline of industry, Washington County became one of the poorest in the state. Unemployment remained high and the town of Plymouth emptied out, losing population every decade from 1970 to the present.

Today, Washington County is showing signs of renewal. Farms still dominate the landscape, and agriculture remains the primary economic engine. But the county is also starting to attract tourism. Somerset Place and Pettigrew State Park attract thousands of visitors each year. Plymouth has been the site of new development, especially on its waterfront. There are new restaurants and several museums in the town, along with several historic restoration projects.

The county’s towns also benefit from Outer Banks traffic because of their location on U.S. 64. But because of its distance from the beach or major towns such as Elizabeth City or Greenville, Washington County will likely remain a testament to North Carolina’s agricultural, small-community past.