Summer Michaud-Skog has called a small coastal town in Oregon home the last few years during the pandemic.

Before the world stopped, she had been traveling the country in her mother’s old minivan, establishing chapters of Fat Girls Hiking and finding accessible hiking trails.

Supporter Spotlight

Fat Girls Hiking, a group she founded in the mid-2010s, is described as a nationwide fat activism, body liberation and outdoor community to take the stigma out of the word fat and empower people to live their best life. Fat Girls Hiking has more than 37,000 Instagram followers and nearly three dozen official chapters across the country.

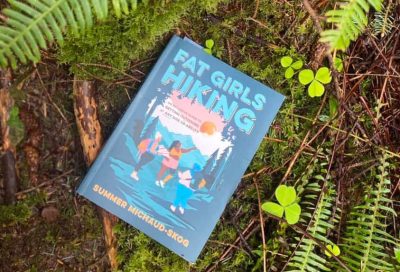

After Michaud-Skog’s cross-country trip, she was approached by Timber Press in Portland, Oregon, to write about the Fat Girls Hiking community. “Fat Girls Hiking: An Inclusive Guide to Getting Outdoors at Any Size or Ability” was published March 29 and is available online.

In 2014 when Michaud-Skog, who is now in her early 40s, and her girlfriend at the time began hiking frequently, she didn’t often see people that looked like her on the trails or on outdoor-focused social media.

“I am a queer, fat, heavily tattooed woman with chronic pain who hikes in dresses,” Michaud-Skog writes early in the book. “I don’t have money for ‘proper’ outdoor gear and most of it doesn’t even come in my size, so I get by with what’s available.”

She wrote that often during their hikes, especially during challenging sections, they would sing “we’re just two fat girls hiking.” It made them laugh. “It was a comfort to know that it didn’t matter to us that we were fat girls hiking, we just loved being outside.”

Supporter Spotlight

The next year, in 2015, Michaud-Skog began looking for diversity in outdoor social media. She decided to create the Instagram account, Fat Girls Hiking. “I shared photographs and wrote about trails, campsites and road trips.” She also has a Fat Girls Hiking Facebook page. The community grew through the online presence, evolving into in-person meetups.

In the book, she stresses that the goal of Fat Girls Hiking is not to lose weight but to create a community “where fat folks could be outdoors together.” She uses the phrase, “Trails Not Scales” to emphasize the importance of “a fat outdoor community that isn’t focused on weight-loss or diet talk.”

Michaud-Skog, who spent her youth in rural Minnesota, and others in the Fat Girls Hiking community share in the book how they found their place outdoors.

“The FGH community is full of people with lots of different identities and backgrounds who come together to support one another and find joy and healing in one another’s company,” she writes. “Each member is finding their own ways to connect to the outdoors.”

She also writes advice on how to hike, what to wear, equipment, what to bring and other ways to make hiking in larger bodies more comfortable, which can be applied to many outdoor activities.

In a recent interview with Coastal Review, Michaud-Skog explained that though the name is Fat Girls Hiking, the community is not just for fat girls and not just hiking. Instead it’s pushing back on the idea of who representation in the outdoors, and to redefine what it means to be a hiker and to hike.

“It doesn’t have to be a certain mile. It doesn’t have to be a certain elevation gain, I think the most important thing is to go somewhere,” she said, whatever is accessible, if it’s the wetlands, old-growth forests, “find something that excites you.”

The “gatekeepers,” as she calls them, can happen in any industry and are those saying you have to do this a certain way and be wearing a certain thing, otherwise it’s not considered a real hike.

“For me, it’s a hike if you’re outside walking in nature. It’s a hike, and I think it’s the intention. You don’t have to let other people define what the hike is,” she said.

Michaud-Skog said that you can use mobile apps or Google to find features that pique your interest and stir the motivation.

“I really got into birding when the pandemic started, so that was really exciting to me,” she said, “I honestly never thought that would interest me but now I am fascinated with different types of birds.”

She bought binoculars and a book on birds and spent a lot of time outdoors birdwatching, she said.

It’s a fun activity to do outside, she continued, and feels like the pace of the activity, particularly for slower hikers, those with chronic pain or a disability, is pretty accessible, especially if you have like a place to sit. “And it’s a really cool connection to nature because you get to see birds up close. To me, it’s exciting.”

Michaud-Skog explained that hiking also motivated her try other outdoor activities.

“I think it really inspired me to try things that I didn’t think that I could do because of the size of my body. Would it be different? And how would it be different?” she said. “I think for me doing a lot of research on a particular activity that I want to try before I would do it is really helpful.”

She cited kayaking and paddleboarding as examples of popular activities on the coast that may seem inaccessible for some body types.

“There are things you need to think about with something like kayaking or stand-up paddleboarding,” such as, is there a weight limit? “This is something that I think people who maybe aren’t fat or plus size, they wouldn’t even think about … that it might not even work for somebody who’s a certain way.”

Michaud-Skog leads retreats where participants do more than hike, and she has to call ahead and ask if the equipment works for people who are this size or that size.

“And so for me, I think the easiest way for me to feel more comfortable in taking up space is to have the information that I will need in order to feel comfortable, or at least know what to expect when I get to the outfitter, or get to the place where I’m going to rent a kayak. Do they even have gear that’s going to accommodate me? That’s really important.”

Many don’t want to put themselves in an uncomfortable place by trying something new, but Michaud-Skog said doing so was an experience of personal growth for her.

“Even if maybe I didn’t do well, because a lot of times trying new things — especially if you’re not a person who’s represented usually in kayaking or watersports — you’re probably not going to be good at it,” she said. That can be really hard for some, but the confidence comes after, not when you’re doing it.

She said people tell her all the time that the outdoors is for everyone, and she fully agrees, “but the thing that’s tricky is (that) we’re not all represented in the same way,” and that’s especially true for people who have access needs, including wheelchair users or those with chronic pain.

If a person wants to get outdoors, Michaud-Skog said its critical to know what their body needs and not allow shame to interfere with those needs.

“If you’re outdoors and need to sit down, there’s nothing wrong with that,” she said, adding that while it may not look like how other people hike a trail, it’s what you need, and once we are able to meet our own needs, we grow trust and confidence. “Plus, having that connection with nature is so special. It really improves our mental well-being,” Michaud-Skog continued.

It’s also good for the environment, she added.

“I think (that) if more people are in love with nature, more people are going to want to protect it,” she said. “The more people we have in the world who say ‘I want to protect natural spaces, and I want future generations to have access to this’ — that’s really important to me, too — but it starts with people being able to feel comfortable to go out there and take up that space and see the amazing beauty that nature has to offer.”