In a lovely book called “Finest Kind: A Celebration of a Florida Fishing Village,” Ben Green remembers how his ancestors and other families left Carteret County, North Carolina, in the 1880s and established a new fishing village 600 miles south on the southwest coast of Florida.

First published in 1985, Green’s book describes the founding of Cortez, now known as the last fishing village on the Florida Suncoast. The village is 35 miles below Tampa, on the north end of Sarasota Bay.

Supporter Spotlight

“This book is an attempt to capture the richness and joy of the people of Cortez and also, with unashamed subjectivity, to raise the deep moral and political questions of whether this nation as a whole, and the state of Florida, in particular, can afford to lose these few small communities that remain. In short, can a nation afford to destroy its traditions and roots, and at what price?”

David Green, “Finest Kind”

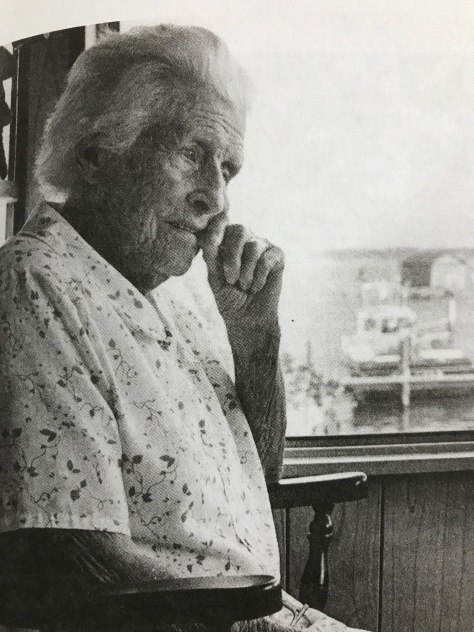

When he was researching “Finest Kind,” Green talked with Cortez’s oldest resident, Lela Garner Taylor. She wasn’t one of the village’s very first residents, but she arrived there only a couple decades after the first group of migrants made the trip from Carteret County.

“I was born in Carteret County, North Carolina, on the 28th of January, in 1888,” she told him. “We lived right on Bogue Sound.”

In 1907, Miss Lela married a sharpie captain named Neriah Taylor. At the time, he was making his living by towing logs to the local lumber mills.

Supporter Spotlight

By then, Carteret County watermen had been leaving home and heading for southwest Florida for years. Neriah had apparently gone mullet fishing down there at least once, then returned home.

He must have liked the wildness of the place and the feeling of being on a new frontier. At the turn of the century, settlements were still few and far between all the way from Sarasota Bay to the Everglades.

In those days, the Everglades still reached all the way to Lake Okeechobee. All along that part of the Gulf of Mexico, land speculators, railroad interests, phosphate barons and sprawling seaside resorts would later hold dominion, but they had barely gotten a foothold yet.

In 1900, Naples still only had about 80 residents. Fort Myers had only a few hundred. Even Tampa was still just a little town.

What southwest Florida did have though was endless miles of mangrove swamp, remote keys and wild barrier islands — and fish. Lots of fish.

Foremost among those fish were striped mullet, or as people in Carteret County call them, “jumpin’ mullet.” For much of the 19th century, Carteret County’s salt mullet trade had been one of the largest saltwater commercial fisheries anywhere in the southern states.

Jumpin’ mullet was the fish that bound Carteret County and southwest Florida together.

On the southwest coast of Florida, fishermen had also been catching mullet and salting the fish and roe for generations.

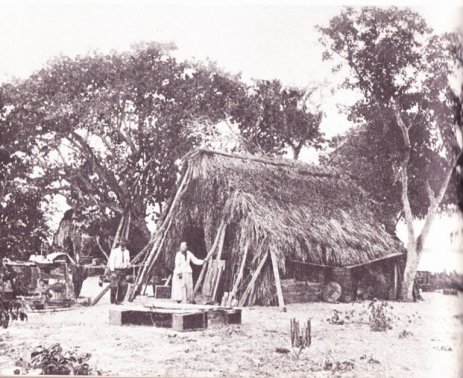

In fact, according to Yale historian Michelle Zacks’ wonderful study of mullet fishing in Southwest Florida, Spanish fishermen from Cuba had been visiting those waters and harvesting mullet for shipment to Cuba since at least the late 1600s.

On the mullet fishing grounds, Dr. Zacks recounts, the Spanish fishermen worked early on with Calusa Indian fishermen, and later with Creek and Yamasee Indian fishermen, as well as with fugitive enslaved people.

Dr. Zacks goes on to note that by the late 1800s mullet was by far Florida’s largest fishery and salt mullet and mullet roe were mainstays on people’s dinner tables, particularly in the rural parts of the state.

She quotes one observer in Florida back in those days saying that salt mullet was sometimes “on the table…three times a day.”

The salt mullet trade to Cuba began to fade at the end of the 19th century, however. In the 1880s and 1890s, the first railroads reached Tampa. The railroads then began to inch further into southwest Florida, opening up the fresh fish trade to other parts of the United States for the first time.

Like so many in Carteret County, Miss Lela’s husband wasn’t going to miss out on the opportunity.

“So in July of 1911 we come on the sharpie to Morehead (City), me and him and our first two children, and then we got on the train to New Bern and stayed the night,” Miss Lela told Ben Green.

They took the train to Tampa, boarded a steamer down the coast to Bradenton and then took a taxi to Cortez.

“Once we got settled I liked it,” Miss Lela remembered. “But that first year I was still so homesick for North Carolina that I cried all Christmas Day.”

* * *

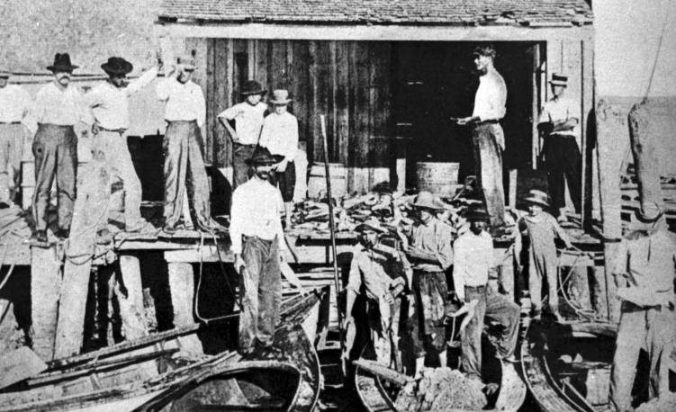

Ben Green’s great-grandfather, Billy Fulford, and two of his brothers had arrived in Cortez even earlier. In doing the research for “Finest Kind,” Ben discovered that they left a Carteret County community called the Straits sometime in the early 1880s.

At the time, Capt. Fulford, as he came to be known, was just a young thing, barely 18 years old.

The Fulford brothers first tried fishing at Cedar Key, and then made another go of it at Perico Island. They finally settled down at a place called Hunter’s Point, which had a nice little harbor looking out on Sarasota Bay.

Anna Maria Island and Longboat Key offered the harbor some protection from storms, and the local fishing boats could reach the mullet fishing grounds in the Gulf of Mexico via Longboat Pass.

Others from Carteret County soon joined them. They included people with surnames that anyone from the North Carolina coast would recognize in a heartbeat: Guthries, Willises, Fulfords, Chadwicks, Taylors, Lewises and others.

Some came from the tidewater farm country along Bogue Sound. Some came from the fishing villages east of North River. Some came from the “Ca’e Banks” and others from the neighborhood known as the Promise Land.

Some were farmers weary of trying to make a living on the land.

Ben Green interviewed one of those farmers, a latecomer to Cortez (as the village came to be called) named Earl Guthrie.

“I was raised on our farm and that’s where I done my work was on that farm,” Mr. Guthrie told Ben. “I decided I didn’t want no part of farming and that’s why I come to Florida.” He arrived in Cortez in 1921.

At the time he could get a train ticket from North Carolina to Tampa for $20.13. “Every one of them Guthrie boys up there (in Carteret County), as soon as they was growed, they’d head for Florida,” he recalled.

If they could not afford a ticket, they jumped on a boxcar and rode down that way. “That’s how a lot of them come, by boxcar,” Mr. Guthrie said.

Some only stayed in Cortez during the mullet fishing season in the fall and winter. Then they returned to Carteret County and helped their families on the farm the rest of the year.

In “Finest Kind,” an older gentleman named Grey Fulford recalled his childhood in Cortez. His father had died in the big flu epidemic of 1918, so his mother Mamie made her living by running a boardinghouse.

He remembered that most of Mamie Fulford’s boarders were those young Carteret County fishermen. In most cases, they had come to Cortez for the fall roe mullet season and then went back home.

“She’d charge them about $5.00 a week and another 50 cents to do their laundry,” Mr. Fulford told Ben Green.

“Sometimes she’d have 6 or 7 of them at a time sleeping on cots in the old house we rented out. It was like a hotel. Momma had two old wood stoves and she hired two other women to help with the cooking, and Grandma would help with the biscuits and the cornbread.”

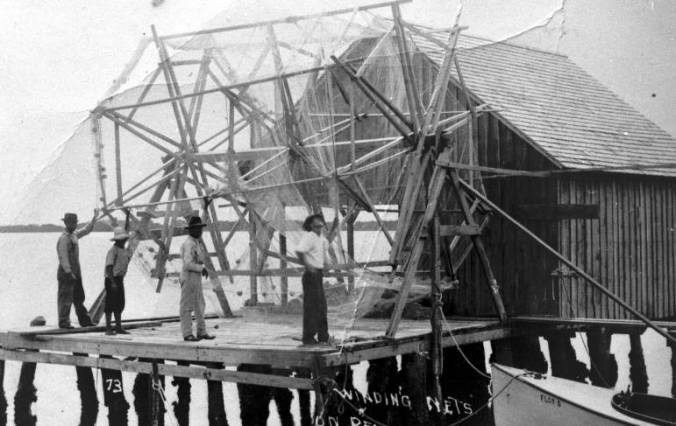

Other Carteret County fishermen settled down in Cortez. They started fish houses and boatyards and little stores. Before long, the village had a school, a church and a post office.

There were, of course, setbacks in Cortez, and none was worse than the great hurricane of 1921. That storm scoured the village’s waterfront, washing away all the fish houses and most of everything else, too.

The Great Depression was hard there too and made harder when the mullet mysteriously vanished for most of a decade.

Yet the village didn’t give up. While real estate developments and resorts grew up in the distance, Cortez remained tied to the sea and to Carteret County.

Well into the 1930s, Cortez’s children would sometimes return to Carteret County to work on local fishing boats for part of the year, often alongside a grandfather or a great-uncle.

At the same time, new young men and women from Carteret County kept showing up in Cortez, most of them looking for adventure and a fresh start in a place that felt a lot like home.

Coastal Review is featuring the work of historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.