Coastal Review is now featuring the historical analysis of author Eric Medlin.

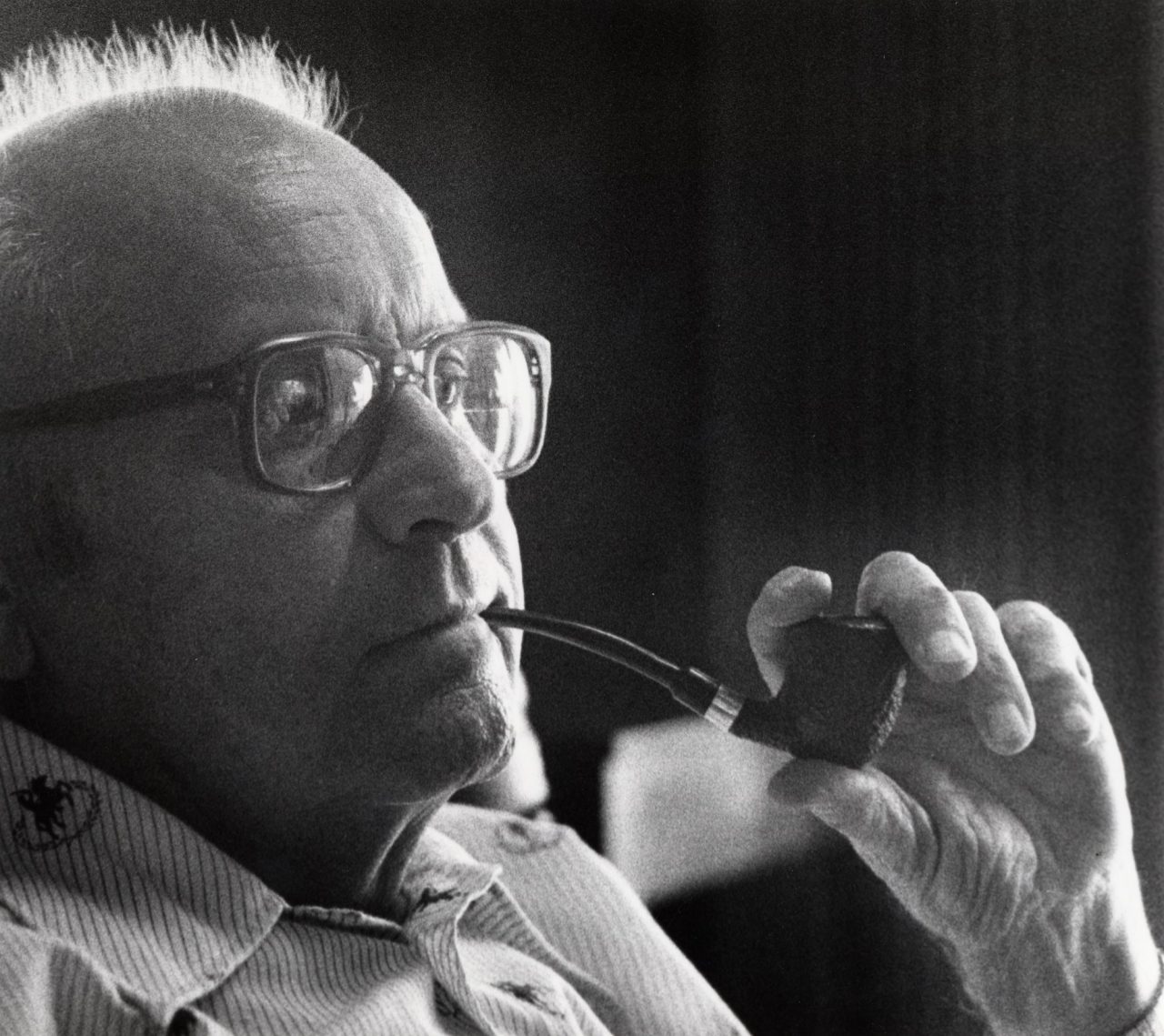

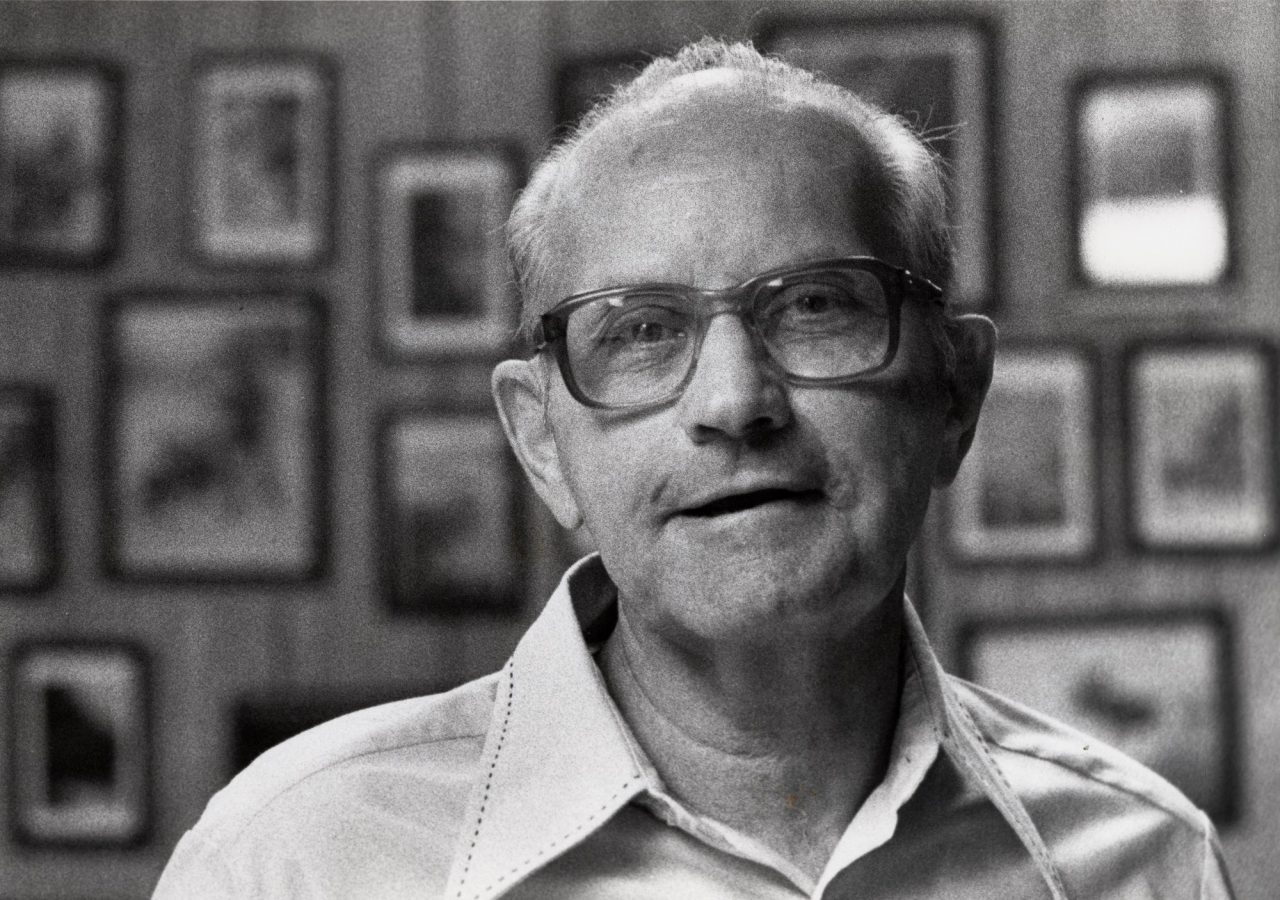

From the Croatan and Roanoke tribes to the Sir Walter Raleigh expeditions, the region has attracted peoples interested in its crisp beaches and myriad of waterways. Many men and women have attempted to tell the history of this region since the 17th century. But one, David Stick (1919-2009), rises above the rest in the eyes of both historians and many of the region’s inhabitants.

Supporter Spotlight

Stick was not just a talented writer and researcher. He was a local businessman, a supporter of the economic and environmental well-being of the coast, and in many ways the platonic ideal of a local historian.

David Stick was born in 1919 in New Jersey. His father, Frank Stick, was an outdoor photographer and illustrator who was lured to the Outer Banks’ lush scenery and real estate opportunities. Frank became a successful developer, lobbied for the creation of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, and eventually illustrated some of his son’s books.

David began his career following his father’s love of the ocean. After a stint at the University of North Carolina and in the military, he returned to the Outer Banks and became a real estate broker. He did not stop with houses and land, however. Stick developed a new town, Southern Shores, where he served as mayor and worked on the town’s distinctive flat-roof homes.

Over the years, he diversified his holdings beyond real property. In a 1985 retrospective, William S. Powell named a handful of Stick’s many interests: “a land company, a contracting firm, a motor lodge, a craft shop, a bookshop, and a publisher of maps.”

Stick’s success in business allowed him to pursue his love of his adopted region. He began to collect materials about the Outer Banks, a collection that later served as the basis for the Outer Banks History Center. Stick served on planning boards and in governmental positions where he could act as a booster for the region.

As county commissioner, Stick began to update the county’s antiquated government structure. Stick also began to write history, with his first book, “Fabulous Dare: The Story of Dare County, Past and Present,” being published in 1949. History became his most important legacy. Stick ended up writing 13 books and going on numerous media tours sharing his love of coastal North Carolina.

In many ways, the trajectory of Stick’s life matched the plan for local historians set out by Albert Ray Newsome, secretary of the North Carolina Historical Commission. In the 1928 Biennial Report of the North Carolina Historical Commission, Newsome wrote that he wanted each county to have a historian and for that historian to be rooted in the local community. They were not doctoral students who pored over archives for months or years to complete a dense monograph on a local county or town.

Supporter Spotlight

Instead, Newsome intended these men and women to be locals who knew the people and environment of their communities from decades of lived experience. They would immerse themselves in a county, learn all there was to know, and then write down what they had learned for both the local community and the outside world.

Stick fit Newsome’s mold perfectly. He was not just a businessman of the Outer Banks but a lifelong resident and enthusiast. In a 1987 speech, Stick reminisced about his life as a newspaper reporter and diver on the Outer Banks. He found shipwrecks, speared fish, and sailed throughout the islands. Stick eventually retired in Kitty Hawk and moved to a house where, during breaks in writing, he could “look down on my dock and the little boathouse at the end, and gaze — often for long periods, when I really should be writing — at the broad expanse of Kitty Hawk Bay stretching south and west to the horizon …”

Even though he was not born in the region, he was as much of a local as many other residents, most of whom were themselves transplants by the 1960s and 1970s.

But Stick went far beyond many of his local contemporaries and antecedents. In a word, his history was good. Stick’s work won national acclaim. His first UNC Press book, “Graveyard of the Atlantic,” published in 1952, received positive reviews from the New York Times Magazine and the New Yorker. A reviewer in the Journal of Southern History proclaimed it an excellent work that was “written in an interesting and nearly fictional style which causes the reader to feel the terror of the shipwrecked as well as the determination and sometimes helpless feeling of the lifesaving personnel.”

Six years later, “The Outer Banks in North Carolina, 1584-1958” was lauded in the North Carolina Historical Review as “an excellent addition to the growing literature on the history of the Tar Heel state.”

Each of Stick’s books were meticulously researched, with “Graveyard of the Atlantic” containing six pages of references and a list of over 600 individual shipwrecks off the coast of North Carolina. Stick’s books sold nearly a quarter of a million copies during his lifetime, a remarkable achievement for a local historian, and nearly all of them are still in print. In 1987, Stick became the second local historian to win the North Caroliniana Society Award, one of the highest lifetime achievement honors for a North Carolinian involved in history.

Stick’s approach to historical writing is currently endangered. Pressure on the publishing industry has led to fewer books written for small, local audiences. Their work falls outside the rigorous, competitive nature of academic publishing and the wide audience of popular publishers.

Stick’s life and legacy, both of his books and his many business projects, were dedicated to preserving and telling the story of his adopted coastal home. We hope that legacy will push more historians to follow in his footsteps and reverse the current downward trend of local history.