Even though life on the North Carolina coast changes drastically between generations — from the Civil War, to two World Wars to taking part in the environmental movement — women have had a hand in state history.

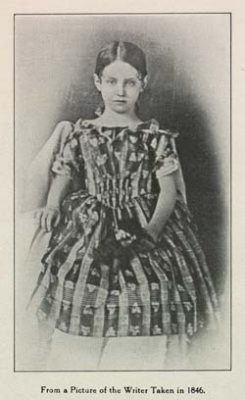

Mary Norcott Bryan was born in New Bern in 1841, 20 years before the start of the Civil War. She spent her childhood at Woodlawn Plantation and then attended boarding school in Washington, D.C., which was her “most delightful experience, and which quite made up for anything bad that had gone before.”

Supporter Spotlight

Recollections of Dixie.”

Bryan wrote her memoir, “A Grandmother’s Recollections of Dixie,” around the turn of the century “to recall some recollections of old times in Dixie.” It was originally a collection of letters to tell her grandchildren about the antebellum South and what she describes as “the delightful plantation life at Woodlawn, (a) phase of society (that) is a thing of the past.”

According to National Geographic, the plantation system developed as British colonists came to Virginia and divided the land up into areas that could be farmed. The Southern economy depended on the crops that the farmers cultivated, and this need for agricultural workers led to slavery being established and the atrocities that followed.

This enslavement furthered the class divisions that already existed between the rich and the poor in the South. In the Southern colonies, “a few wealthy, white landowners owned the bulk of the land, while the majority of the population was made up of poor farmers, indentured servants, and slaves.” The divisions became more prominent than the ones found in the North.

In “Recollections,” however, Bryan remembers her plantation life fondly.

Her difficulties came from “the destruction of her home, the poor treatment she received from Union officers, and the desperate plight of southern civilians during the hostilities,” Harris Henderson writes in Documenting the American South, a digital publishing initiative.

Supporter Spotlight

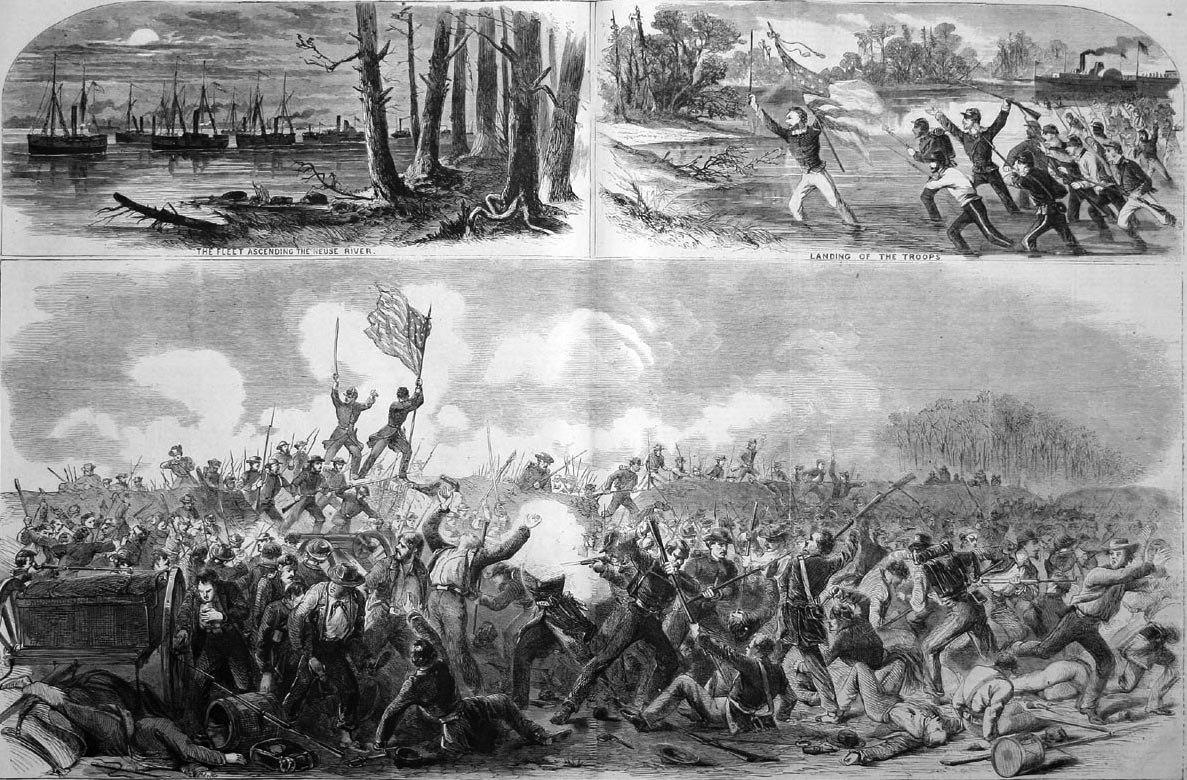

The beginning of the war concerned New Bern natives because the city was in “an exposed position, (so) it was thought best for as many women and children as could leave to do so,” Bryan says. Following their leave from the city, the battle of New Bern took place in 1862.

Even after the war ended, life in the South did not get easier. “Raleigh was now filled with wounded and disabled soldiers; the churches and every available space turned into hospitals,” Bryan writes. “Many poor men were on the benches some in high delirium, some in the agony of death.”

In her memoir, Bryan, who was also a Ku Klux Klan supporter, recalls the Reconstruction period being worse than the war itself. History explains that Reconstruction was “the effort to reintegrate Southern states from the Confederacy and 4 million newly-freed people into the United States.”

In her memoir, Bryan, who was also a Ku Klux Klan supporter, recalls the Reconstruction period being worse than the war itself. History explains that Reconstruction was “the effort to reintegrate Southern states from the Confederacy and 4 million newly-freed people into the United States.”

“The after effects were as trying as the war itself, the disgusting Reconstruction period was a disgrace to all concerned,” Bryan writes. “In some ways these times were worse even than the war.”

“When we returned home…we found our beautiful and valued farm an abandoned plantation,” Bryan writes. The trees had been cut down, slave cabins had been dismantled, and “the old Colonial brick dwelling, made of bricks from England, was razed to the ground. Houses, cattle, sheep, of course, gone, and an apple orchard of choice apples destroyed.”

Rachel Carson was a writer who focused her work on nature and society, but from a completely different perspective. Carson was born in Springdale, Pennsylvania, in 1907. She served as a marine scientist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and conducted research along the North Carolina coast.

During the Great Depression, Carson wrote radio scripts for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries and ended up becoming editor-in-chief of all the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s publications. When she saw the reckless use of chemicals and pesticides during World War II, Carson decided to act.

She had published “The Sea Around Us,” about sea life throughout the year, in 1951. In 1962, she published “Silent Spring,” which focuses on the danger of widespread pesticide use. The latter became such a phenomenon that it is argued to be the start of modern environmentalism and led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA.

According to the EPA website, the organization “may be said without exaggeration to be the extended shadow of Rachel Carson.”

“Silent Spring” exposed the dangers of using the DDT pesticide, originally used to fight diseases among soldiers and civilians and quickly became a pick for insect control. She worried both about how human bodies were supposed to adapt to chemicals and the ones that were used in what she describes as “man’s war against nature.”

“What happens in nature is not allowed to happen in the modern, chemical-drenched world,” Carson writes, “where spraying destroys not only the insects but their principal enemy, the birds.” The pesticides upset the balance of nature because when the insects come back, the bird won’t be there to “keep their numbers in check.”

When President John F. Kennedy read excerpts of “Silent Spring,” first published in the New Yorker, he had the Life Sciences Panel of the President’s Science Advisory Committee, or PSAC, look into her claims.

According to the Environmental & Society Portal, Rachel Carson and the press considered the PSAC’s report, which had been approved by the President, to be “a vindication of the book.”

The writer’s lasting impact goes beyond her lifetime. The Girl Scouts of Western Pennsylvania developed the Legacy of Conservation badge to encourage girls to “get outside while teaching (them) about environmental stewardship.” There’s also a Rachel Carson Reserve, a complex of islands across Taylor’s Creek from downtown Beaufort, to provide stewardship “for the health and prosperity of ALL North Carolinians.”

Carson was intent on bettering the health of the earth and the people who live on it.

“Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts,” Carson writes. “There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature — the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.”

Learning about the past means confronting all of history, the good and the bad. Historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast, knows this full well.

“One of the things that I have learned about studying North Carolina history is that it is (nearly all) ‘blatantly wrong,'” he said. “Every monument and memorial and painting I saw when I visited UNC campus, every historic site and marker…were designed…to keep me and others from learning NC’s real history — and above all, to keep us from questioning white supremacy.”

Historically, because whites had the most power, they had the ability to erase narratives or corrupt them.

“This is the nature of how power works,” Cecelski said. “We can explore the state’s history and see through that veil of untruth and … when we do, our world today makes much more sense.” After we do that, we can begin to move forward.

“When we have confronted ‘our difficult history’ (which is most of our history),” he said, “it then gives us this remarkable chance for creativity– to build a new way of being, a new sense of community with one another, a more honest and fruitful relationship with those that came before us.”