First in a two-part series

Jellyfish are some of the coolest looking creatures that live in North Carolina’s waters. Found in all coastal areas of the state, there’s a dozen different species that can be observed at various times of year while swimming, scuba diving, snorkeling or simply walking along the beach.

Supporter Spotlight

There are two types of jellyfish, or gelatinous zooplankton in North Carolina — true jellyfish and comb jellies, or ctenophores. True jellyfish pump water for propulsion by using the bell on top of their bodies to first contract and then relax their bodies to move water, hence pushing themselves forward in the water column.

Comb jellies do not pump water to get around. Instead, they have eight rows of hair-like structures called cilia all around the outside of their bodies. By moving the cilia in a wavelike pattern, they slowly move through the water column.

There are several species of marine jellyfish found in North Carolina waters. The first group belongs to the class Scyphozoa, and are considered to be “true jellyfish,” or “jellies.”

Lion’s mane

The largest species in North Carolina waters is the lion’s mane jellyfish. This species is easy to identify, as it is the only jellyfish that is orange in color in the typical size range of 6 to 12 inches across at the bell.

This species is also known as the winter jelly, because it prefers the colder waters along the North Carolina coast after the Gulf Stream has moved farther offshore during winter months. Lion’s manes are usually considered moderate stingers, and symptoms of a sting are similar to that of a moon jelly, but with a little more discomfort.

Supporter Spotlight

It is the largest known jellyfish species in the world. Its name was inspired by its showy, trailing tentacles that resemble an African lion’s mane.

The largest specimen of lion’s mane jellyfish ever caught was found on a beach in Massachusetts Bay in 1870. Its bell measured 7 feet, 6 inches across, and its tentacles were 120 feet long. I would not want to meet up with this guy underwater.

The lion’s mane uses its stinging tentacles to capture, pull in and eat with a diet of fish and smaller jellyfish that get too close to the tentacles. Its nematocysts, or stinging cells, are not known to be fatal to humans, however, the sting location will be reddish in appearance and rather painful.

Seabirds, all sea turtles, giant ocean sunfish and other jellyfish species will feed on lion’s mane jellies.

Sea nettles

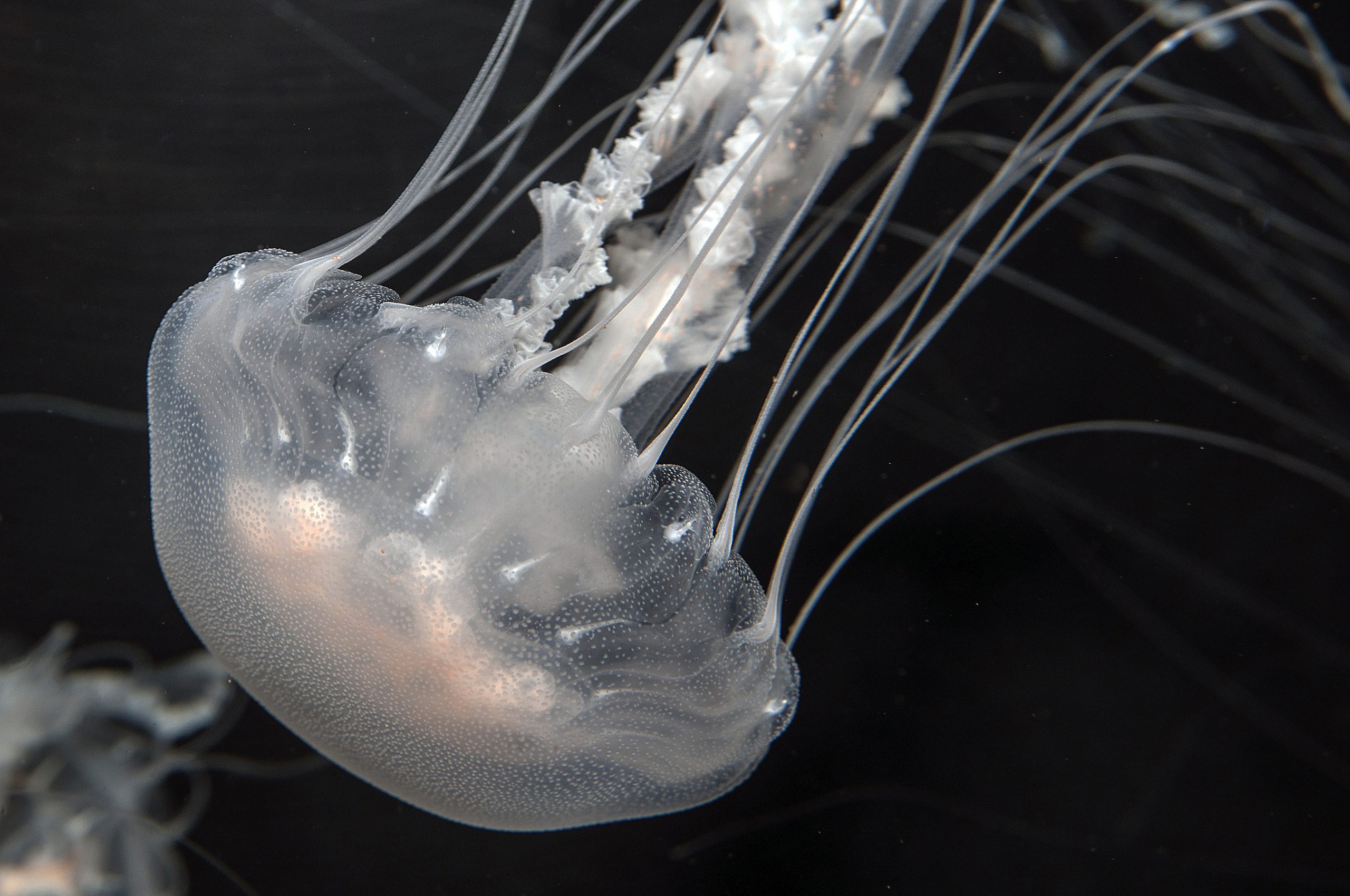

The second-largest jellyfish is the sea nettle. Sea nettles are quite common, being found in tropical and subtropical parts of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans.

Sea nettles are carnivorous — they will feed on ctenophores and other jellyfish as well as crustaceans. Its mouth is in the center of its body near the bell and opens to a stomach-like organ used for digestion.

This species is semitransparent, with small white dots and reddish-brown stripes. Its sting is considered to range from moderate to severe and is fatal to small prey. It is not strong enough to kill humans.

Sea turtles, ocean sunfish and larger jellyfish prey on sea nettles.

Moon jellies

One of the more otherworldly jellyfish is the moon jellyfish. These look like underwater flying saucers.

Moon jellyfish are most common during the summer months from early June to September, when they appear in harbors and bays, looking like a wall-to-wall blanket so thick at times it appears you can walk across them.

This translucent species averages about 6 to 8 inches in diameter at the bell. Larger specimens have been known to grow as large as 20 inches across. They have 4 horseshoe-shaped gonads in the center of the bell and short tentacles.

Moon jellyfish feed on medusae, plankton and mollusks with their tentacles and bring the food back into their body for digestion.

They are only able to move slightly by themselves and rely more on ocean currents even when swimming by pulsing and relaxing their bell.

Moon jellies breathe oxygen from surrounding waters by way of a thin membrane that covers the tops of their bodies.

Moon jellies are a frequent snack for ocean sunfish and sea turtles.

Cannonballs, or cabbagehead

The most common jellyfish found in North Carolina is the cannonball, which is also known as the cabbagehead jelly or jellyballs. During summer and fall, large gatherings of this jelly take place near coastal areas and in the mouths of North Carolina estuaries.

While this species is the most abundant jelly, it is also the least harmful to humans. It has the weakest sting of all jellies found in local waters. Easy to identify by their white bell with chocolate-brown bands, they have no tentacles, just fingerlike appendages hanging down from the bell.

Mushrooms

Mushroom jellies are commonly mistaken for cannonballs, but they lack the brown bands of the cannonball. But this species is similarly harmless to humans, with a mild sting, if felt at all.

According to the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, the mushroom jelly has a firm and dense swimming bell, however its bell is usually flatter than that of the cannonball. The bell does have arms grow down from the center. An adult can have a bell to up to 20 inches across at the widest point.

The bell may be creamy white to light yellow, brown, blue, pink or green. The arms might have yellowish, or brown markings.

Sea wasps

The sea wasp jelly is the most dangerous to humans, and the most venomous of all true jellies found in North Carolina waters. Its sting can give quite the jolt followed by a severe skin rash. A sting may lead to a trip to the hospital, depending on the reaction severity. If stung in the face or neck area, it’s best to seek medical help as soon as is possible.

“There are two possibilities of sea wasps possibly found here: Tamoya haplonemaand, and Chiropsalmus quadrumanous,” said Paul Mazzel, marine science educator at the North Carolina Aquarium Roanoke Island. “While they’re in the same class, I think it’s important to refer to them as ‘sea wasps’ to distinguish them from the highly deadly box jellies of Australia.”

Next: Ctenophores