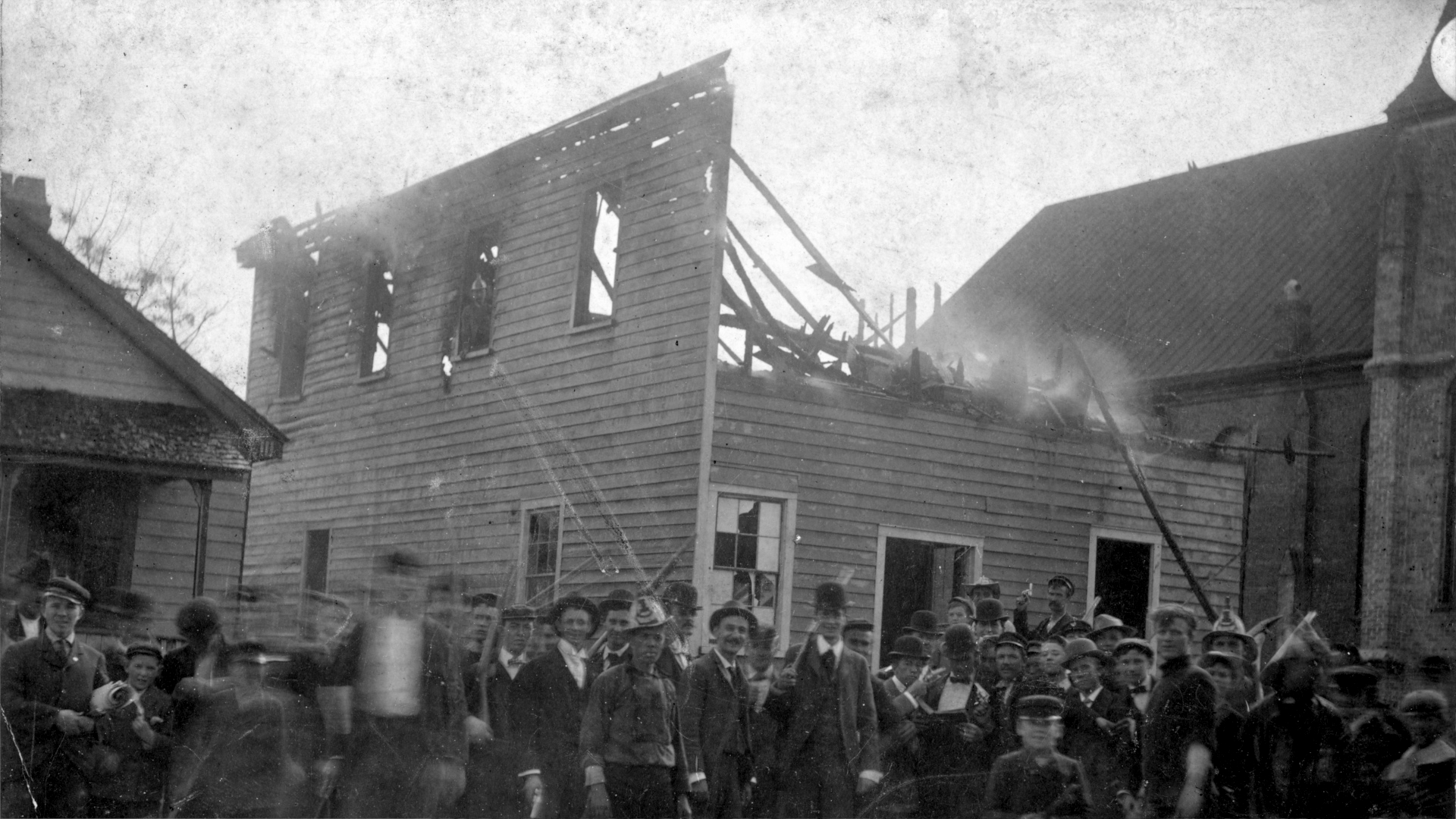

On Nov. 10, 1898, following that year’s election, there was a bloody attack on Wilmington’s African American community.

During what has long been called the Wilmington Race Riot but is now referred to more often as the Wilmington Massacre or the Wilmington Insurrection, a white mob overthrew the legitimately elected government.

Supporter Spotlight

The mob destroyed the local Black-owned newspaper office, chased Black officials and community leaders out of the city and killed many in widespread attacks, according to the North Carolina Division of Historic Sites and Properties, a state program of 27 historic sites. As a result, more than 2,000 Black residents left Wilmington, turning it from a Black-majority to a white-majority city.

“The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 was a turning point; it set a precedent for race relations throughout the state,” the Historic Sites program said. “The events of November 10, 1898, opened the door for one-party rule in the South and African American disfranchisement and de jure segregation in North Carolina. This system of racial oppression and discrimination continued until the middle of the twentieth century.”

The events of 1898 in Wilmington are the focus of a virtual program hosted free of charge by the Gov. Charles B. Aycock Birthplace in Wayne County and sponsored by the Charles B. Aycock Birthplace Advisory Committee as part of the Division of North Carolina Historic Sites and Properties’ True Inclusion initiative. The initiative aims to tell the most extensive and diverse stories about the state’s historic sites.

Christopher Everett’s film “Wilmington On Fire,” which examines the 1898 massacre, can be viewed Tuesday through Sunday, Nov. 22. There will be an online discussion starting at 6 p.m. Thursday. To register and view the film, visit this link. For more information, call 919-242-5581 or email aycock@ncdcr.gov.

The online conversation Thursday about the film will be moderated by Michelle Lanier, director of the North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites and Properties, with panelists Everett, director of “Wilmington On Fire” and LeRae Umfleet, author of the book “A Day of Blood: The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot.”

Supporter Spotlight

“Wilmington On Fire” features interviews with descendants of Alexander Manly, whose newspaper office was destroyed, as well as Thomas Miller, a prominent businessman and property owner who was forced to leave, and Isham Quick, a coal and wood dealer and board member of the Metropolitan Trust Co. in Wilmington.

Everett said in an interview that his love for history, especially history from his community, the African American community, inspired the film.

“I think it’s very important for our community to tell these important stories through various mediums such as movies, books, articles, exhibitions, etc.,” he said.

He hopes viewers take away from the film the role voting and politics played in the 1898 massacre. “I want viewers to understand the power of voting and the importance of voting,” he added.

Everett said that it was an honor to have his film selected as part of the True Inclusion initiative. “I want the film to be used as a tool to educate and inform fellow North Carolinians on our history and being a part of this initiative helps do so,” he said.

The director is also working on “Wilmington On Fire: Chapter II,” which focuses on Wilmington today and the residents working to bring Wilmington back to what it was before the 1898 massacre. See the teaser trailer here.

Umfleet, author of “A Day of Blood: The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot,” distilled the book down from a 500-page report she wrote as primary researcher in the Wilmington Race Riot Report.

She said she researched the massacre of 1898 while working as a research historian in the research branch for the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. She still works for the department on special projects and the initiatives of the secretary’s office.

The centennial of the violence was in 1998 and the residents of Wilmington came together to acknowledge what happened, to find some ways to build bridges and move forward, Umfleet explained.

“There was a realization that more research was needed to identify the impact of 1898 on the African American community, and so a research commission was established by the legislature,” Umfleet said. Her department was charged with providing the research on the history of the event to the commission.

Her research focus prior to her work on the 1898 massacre and since then has been on giving a voice to communities that don’t have a written record.

“The victims of 1898 were sort of these silent stories that we didn’t really know, and that’s always been my research focus, giving a voice to those victims,” she said.

At first, Umfleet said, she thought the narrative would be straightforward but it’s complicated and multilayered with race relations, economics, politics and women’s history. It took her three years of researching and writing to create the book.

Umfleet said that the narrative of what happened in 1898 is really a false narrative written by the perpetrators who planned and carried out the violence against the Black community. Their narrative, she explained, was that what happened was unfortunate. “It was accidental and spontaneous, and that it was necessary in some ways because the city of Wilmington was corrupt, and responsible leadership had to do what it had to do to return the city to safety.”

But when doing the research, reading accounts and letters, “I learned that it wasn’t a corrupt city, that it wasn’t anything other than part of a larger political campaign to retake control of the city, and even the state of North Carolina, on behalf of the white supremacy platform that was held out by the Democratic Party of 1898. And so, it wasn’t spontaneous, it wasn’t accidental, it was planned,” Umfleet said.

She explained that the Republican Party in 1898 was comprised mostly of African Americans because that was the party of Abraham Lincoln, whose Emancipation Proclamation freed the slaves, and of more progressive white businessmen and leaders.

“The Democratic Party was the party of conservatives, of people who were previously affiliated with the Confederacy, and white supremacy had always been a part of the party platform. Eighteen-ninety-eight was the first time it really took hold,” she said.

At the time, Wilmington was half African American and half white, and had a biracial coalition of city government. Ousting Republican leadership and removing African Americans from positions of power in 1898 resulted in a complete wipeout of the officially elected government.

“That’s why we call it a coup d’etat, because that’s the legally elected government that’s been overthrown by an armed force, and that’s what happened on Nov. 10, 1898, in Wilmington,” Umfleet said.

Umfleet explained that Brantley Aycock was instrumental in the 1898 and 1900 campaigns to perpetuate the command of the Democratic Party.

“He was a speaker who traveled around the state on the white supremacy platform,” she said.

Josephus Daniels, who was the editor of the News & Observer then, said that Aycock was rewarded with the governor’s office in 1900 because of the hard work he did in 1898. “The showing of ‘Wilmington On Fire’ is one step in coming to grips with who their historic site represents, a piece of that True Inclusion.”

State Historic Sites Director Lanier wrote in an An Open Letter for These Times: Black Lives and Historic Sites that through the commitment to True Inclusion, “We will say the names that reveal the impact of black lives on our soil, louder and more frequently. We will commit to sharing more narratives that reveal the histories of racism in our state and beyond.”

Lanier told Coastal Review Online that “The showing of ‘Wilmington on Fire, sponsored by the Aycock Birthplace is a testament to our prioritization of True Inclusion,” as well as the #TrueInclusion social media campaign to say the names if African Americans associated with the state’s Historic Sites and Properties.

The “Wilmington on Fire” film program came about after a meeting with staff at the Aycock Birthplace.

“We met together thinking through some possibilities of programming initiatives that would help tell the world that this site is interested in telling these stories that have not traditionally been told,” she said.

Lanier mentioned to the staff that she knew Everett through her work as adjunct professor at Duke University Center for Documentary Studies.

“The staff at Aycock wanted to create a program that was as close to the anniversary of the Wilmington massacre as possible, and so we worked with the filmmaker, as well as LeRae Umfleet.”

By having the event online during a pandemic, Lanier said the Historic Sites state program can provide a password-protected link to the film as well as an opportunity to participate in the discussion with the filmmaker and scholar about the Wilmington Massacre. This presented an opportunity for people to access public history from the safety and comfort of their home.

“We also feel like it’s a way for people to think about the way politics and power and race have played out for the years, and we hope that people will find these historical lessons useful for even understanding the political climate that that we are witnessing today,” she said.