HYDE COUNTY — As engineers start work on designs to manage water levels and flooding at Lake Mattamuskeet, restoration of its water quality depends as much on a new plan to remove 99% of the invasive common carp muddying the lake.

Unless they’re gone, water won’t clear, lake plants won’t come back and pollution will worsen.

Supporter Spotlight

Currently, there’s more than 1 million carp — a total of about 4.3 million pounds of body mass — swimming in the state’s largest natural lake.

By rooting around for food in the lake bottom, the carp not only stir up harmful levels of nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, the turbidity that it creates in the water blocks sunlight to grow submerged vegetation that attracts migratory waterfowl.

“The challenge is, we need to remove the carp quickly, within one to two years if at all possible,” said Wendy Stanton, biologist at Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge, “because they reproduce very quickly.”

With implementation of the Lake Mattamuskeet Watershed Restoration Plan recently kicked into gear, the refuge is first tapping into funds provided by a $180,000 grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Coastal Funds Program to block the fish from entering the lake, she said. Carp barriers on tide gates will be placed in the four outfall canals that connect the lake to the Pamlico Sound. The canals are the main entry points for new carp coming into the lake. The barriers will not block other fish or crab, she added.

A partnership was formed in 2017 between the Wildlife Service, Hyde County and the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission to address water quality issues at the lake and flooding of the surrounding landscape. The partnership contracted with the North Carolina Coastal Federation to develop the watershed restoration plan, which was finalized in August 2019.

Supporter Spotlight

Stanton said that there are also plans to place some additional barriers at some of the refuge’s main canals that might be other sources for breeding areas for carp. Remaining grant funds will be used to hire commercial fishers to catch the carp in pound nets placed in the canals on the lake side of the tide gates.

“Only carp will be removed from the lake, and all non-target fish, or anything else that ends up in the nets, will be released back into the lake,” she said.

The refuge is currently working on required compliance documents to move forward on “a massive removal” of the fish, Stanton said. Once the environmental assessment and compatibility determinations are completed, they will be put the plan out for public review. The main part of the carp removal, which is funded by another grant, will be completed in 2023.

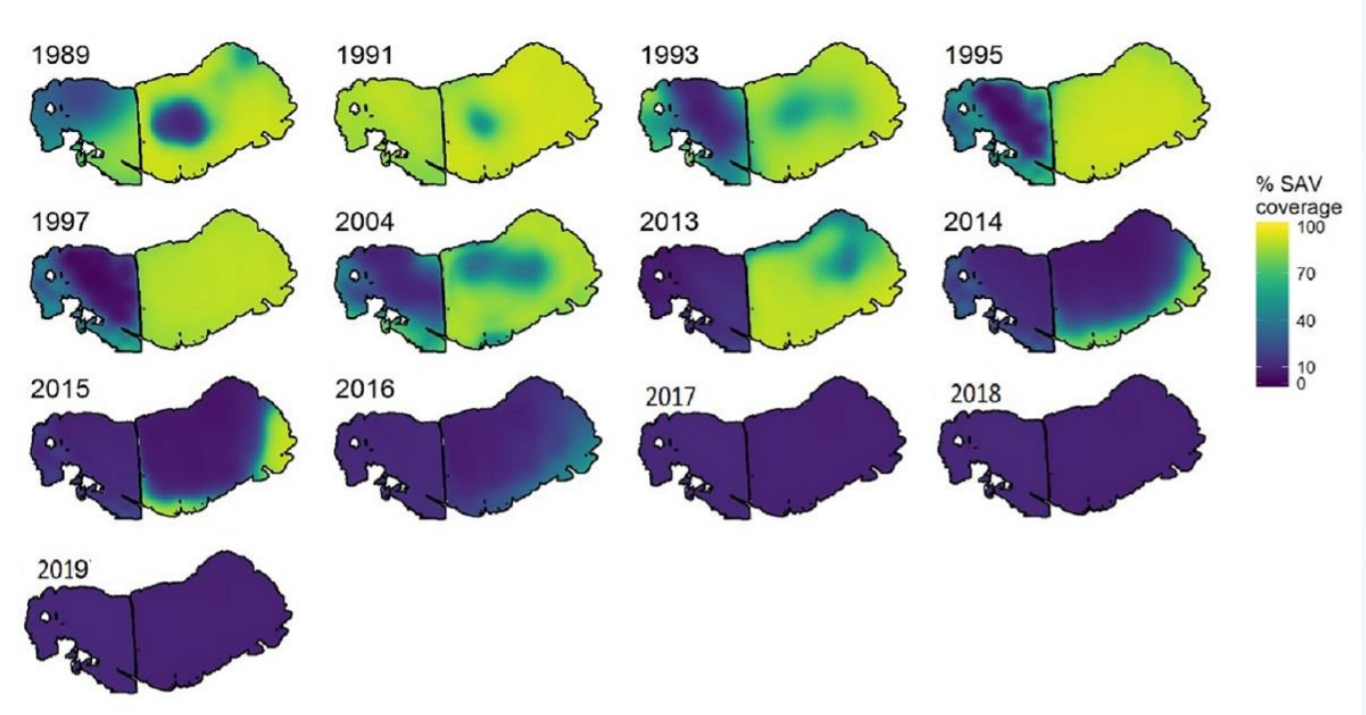

Surrounded by heavily drained farmland and waterfowl impoundments, the shallow, 40,000-acre freshwater lake has been increasingly beleaguered by high water levels and algal blooms. In recent years, its submerged aquatic vegetation, or SAV, had been disappearing and is now completely gone.

Increased nutrients and sediment flowing into the lake caused the state Department of Environmental Quality in 2016 to add Mattamuskeet to its list of impaired water bodies, where it remains. Stanton said the lake was plagued with algal blooms much of the summer from cyanobacteria, which result from warmer water and high levels of nutrients.

Once the carp are gone, Stanton said she expects that other best management practices, or BMPs, recommended by restoration partners will also be put in place to control nutrients and water flow in the watershed.

“And the bottom line is just the quality of the fishing for sportsmen and recreational fishermen and fisherwomen,” she said, “it’s going to be so much better when we restore that lake — the improved water quality and clarity.”

Kendall Smith, Mattamuskeet’s new refuge manager, said that an engineering firm has recently been hired to do a yearlong hydrologic study of the lake and the watershed. One critical challenge the team will address is the persistently high water level of the sound, created by increased rain and sea level rise, that blocks the tide gates from opening. As a result, the lake does not flush, or drain, decreasing water quality.

Regular monitoring of the water level is done, he said, as well as testing for nutrient levels. There also have been numerous studies of the SAV to determine how to restore it to both sides of the lake, which is bisected by a road and connected by culverts. Although the lake is still renowned for attracting thousands of migratory waterfowl, including white swans, most now visit surrounding waterfowl impoundments instead of the denuded lake. The carp, which have been in the lake for decades, did not create the problem, Smith said, and their absence will not be the magic cure.

“So, it’s sort of a complex cycle,” he said. “Now that we don’t have the SAV in there, the SAV is not able to take up some of the excess nutrients. And it’s not able to sort of hold the substrate to provide some structure there.

“We don’t feel like getting rid of the carp alone is going to solve the problem. They’re just sort of part of that problem … Even without the carp, there’s still the algal issues, and the water clarity is not sufficient for SAV growth. It’s kind of a perfect storm, really.”

A consent decree with landowners surrounding the lake was made in the 1930s that allowed them to drain into the lake for perpetuity. Since much of the land in Hyde County is at or below sea level, farmers drain or pump water off their land through canals. In addition to the four main canals at the lake there are countless others on surrounding land, including the refuge.

But the landowners can choose to redirect that drainage and still not give up their right to drain into the lake, Smith said.

“That right is established, it’s not going away,” he said. “But they can certainly voluntarily choose to have that drainage redirected through some type of engineered project which is one of the things that the engineering firm is looking at. So, that’s definitely one of the project ideas on the table.

“It’s definitely part of the discussion, and it’s definitely something we see as key. It’s maybe one of the harder requests, and one of the harder things to solve, because it requires change. It requires some approaching things differently.”

Hyde County has received grant funds for pumps and designs for a drainage district, and there are proposals that will be considered and brainstormed among members of the Mattamuskeet restoration stakeholders’ group to possibly share costs and/or maintenance for drainage infrastructure and improvements.

Part of the complexity, among many, of restoration of Mattamuskeet’s watershed, he said, is that use of the land surrounding the lake has changed, and there are many more privately owned duck impoundments that grow corn to attract ducks – and leave it there.

The refuge has impoundments – created ponds for ducks – that are managed not for crops but for “moist soil vegetation,” he said, and there are no nutrient inputs.

“So, we don’t put fertilizer out there,” Smith said. “However, ducks put fertilizer out there.”

Still, the nutrients on the corn left in private impoundments exacerbates the issue, he said. The increase in nitrogen and phosphorus in the early spring correlates with when the impoundments are emptied.

“It would be a very tough sell for those managers of those impoundments,” Smith said, “but if we could convert those to more natural foods, moist soil where the nutrients inputs were reduced, I think it would significantly decrease the amount of nutrients coming into the lake in the spring when there’s a pump-down.

Michael Cahoon, a Hyde county farmer since 1980 and a member of the stakeholders committee, farms about 2,000 acres, of which 900 drain into the lake.

“The amount of acres that drains into Mattamuskeet Lake has not changed over the last 40 years,” he said. “But the land use has changed. And what I mean by that is 40 years ago, this land was used for agricultural purposes only. Now it has changed, a lot of it to duck impoundments.”

The significant difference, Cahoon said, is when a crop is ready, farmers take the crop and its residual fertilizer off the land. Most of the farmland – as much as 90% – that abuts the lake, he said, has been turned into duck impoundments, although it doesn’t always reach far.

It’s good money to lease out your duck impoundments, he said, and it’s become a big industry in Hyde County.

“When they drain their duck impoundments, that water, which is full of nutrients, drains to the lake,” he said. “I don’t want farmers to get tarred with the same stick as duck impoundment owners are.”

Also, when most farmers on the south-southwest side of the lake pump their drainage through canals, which allows the nutrients and sediment to settle out. Land on the other side, as well as the impoundments abutting the lake, mostly drain directly into the lake.

To Cahoon, the best solution to start would be to maintain the canals so the lake could flush properly.

“I think to get the biggest bang for your buck would be to clean out these canals that have not been cleaned out for years and years,” he said. Of the four canals, only the one on the west end is in good shape.”

As far as expecting landowners to pay for infrastructure, not to mention maintaining and managing it in a drainage district, Cahoon was skeptical.

“There’s no way private landowners can pay the pumping of Mattamuskeet Lake and (the refuge) get the benefit out of it,” he said, especially if it was only seasonal. “Pumping is not free. Pumps wear out. They’ve got to be managed.”

But he said he would keep an open mind, because he is committed to helping the lake recover.

“I love it. I don’t want to see it in the shape it’s in,” Cahoon said. “But I want to see it done right.”

To fellow farmer Kelly Davis, a former refuge biologist and current refuge volunteer and member of the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, viewpoints like Cahoon’s have value what has to be a collaborative task that that appreciates everyone’s individual wisdom and insight.

“I think the process has been really inclusive and careful,” she said about the numerous meetings of the stakeholders group. “You don’t really want to manage for the snapshot. If this is a going to work, it’ll take a lot of people working together.”

Inspired by her late husband Blythe, Davis said she believes on working with nature as much as practical to keep the soil and wildlife on the land and the water off the land. To that end, most of the ditches on her family’s 2,000 acres of farmland in the county – only about 150 acres drain into the lake – are vegetated, and the water is either redirected to wooded land, or drains slowly through the canals to allow nutrients to settle out.

“Right now, the lake is sort of a settlement pond itself,” she said. “It’s really about finding places to move water, slowing it down. And making sure the lake is flushing.”

Davis said she believes that landowners and farmers probably prefer having control of how their waters are moved, rather than having one big drainage system for the entire lake. With time and brainstorming, she said, they’ll figure out solutions, whether they’re mini drainage districts shared between neighbors when it’s really wet, or paying an adjacent property owner to let their drainage settle out on their land before moving it out a different canal.

“They want time to digest and suggest ideas,” Davis said. “These farmers know the land. They know their soils. They know their ridges – they understand their topography. They know the higher spots in the field, the lower spots. They know where the water moves, already.”