The measures put in place in March to curb the spread of COVID-19 have changed how North Carolinians consume and dispose of waste. This is the fifth installment in a series examining how advocacy organizations, local governments and state agencies are adapting to these changes.

One day about five years ago, Paul Schernitzki of Maysville experienced an awakening of sorts while driving to work. The grass along the road he traveled all summer had just been mowed by roadworkers. It was as if a shaved beard exposed oozing sores.

Supporter Spotlight

“I was shocked how much litter there was,” Schernitzki said in a February podcast, recounting the reasons for founding his new educational anti-littering effort, The Litter Pirate. “It blew my mind.”

But safety measures related to COVID-19 have stalled The Litter Pirate’s work, along with other annual or seasonal roadside cleanups organized by the state Department of Transportation and numerous community volunteer groups.

“It just made it a lot worse when the COVID set in, but we were already having budget issues,” Kimberly Wheeless, NCDOT’s litter management program outreach coordinator, said about litter maintenance programs. “The only positive note due to the COVID is, in the beginning, more people were staying home, so there was less litter.”

Both of DOT’s annual spring and fall litter sweeps had to be canceled because of the virus, she said. Cleanups associated with the department’s Adopt-A-Highway program and Sponsor-A-Highway litter sweeps were also rescheduled or canceled.

Supporter Spotlight

But with more people hitting the highways as everything is opening up again, Wheeless added, roadside and parking lot litter now include the addition of masks and gloves. Cigarette butts and fast-food trash continue to be the main component of the garbage, along with plastic bags, straws and bottles, as well as aluminum cans and glass bottles.

During 2019, NCDOT spent $21,665,454 removing litter from 80,000 miles of state routes, according to state data.

To offset costs, the agency has programs such as Sponsor-A-Highway, which offers 1-mile segments of highway to businesses to sponsor in exchange for a fee to pay professional cleanup crews and a roadside sign advertising the business, and Adopt-A-Highway, which offers supplies to volunteer groups to pick up and bag litter on sections of road in their communities for DOT to collect.

Funding for most of the state prison crews that did cleanups in the past has been cut in recent years, although some local governments still use inmates to remove litter. Others pick up roadside litter as part of court-mandated community service.

With or without COVID-19 aggravating the issue, litter has been a costly and unsightly plague on North Carolina, from the coast to the mountains.

In 2019, the Sponsor-A-Highway program removed 577,035 pounds of litter, and Adopt-A-Highway picked up 1,020,870 pounds of roadside trash. Other volunteers reported a total of 77,115 pounds, and NCDOT contract litter maintenance removed 7,253,490 pounds. Also, there was a total of 3,154 litter charges issued with 983 convictions. Intentional litterers could face fines of $250 plus costs.

Keep American Beautiful, probably the most recognized anti-litter nonprofit group, has about 650 certified affiliates nationwide and about 30 in North Carolina.

The group began in 1953 when “a group of corporate, civic and environmental leaders gathered to unite the public and private sectors to foster a national cleanliness ethic,” according to a 2018 press release.

The famous “Crying Indian” public service announcement from 1971, depicting a supposed Native American man (who was actually an Italian-American) on horseback, looking at the polluted and littered environment in his midst. As the camera zooms into his face, a big tear welled from one eye onto his cheek.

But critics of the PSA, often cited as one of the most successful in advertising history, accuse Keep American Beautiful of using the campaign to blame consumers, rather than manufacturers, for the blight.

“Not only were they the very essence of what the counterculture was against, they were also staunchly opposed to many environmental initiatives,” Finis Dunaway, author of “Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images,” wrote in a Nov. 21, 2017, editorial in the Chicago Tribune.

Dunaway contended that the “Crying Indian” purposely deflected attention from responsibility for the environmental blight created by disposable packaging and container industries.

“That narrative is fundamentally untrue,” said Keep American Beautiful spokesman Noah Ullman.

Although most of the founding members of the group, initially called the “Keep Our Roadsides Clean Council,” included corporate representatives from, among others, the National Can Corp., American Petroleum Institute and Paper Cup and Container Institute, it also represented the National Council of State Garden Clubs and the National Parks Association.

Ullman cited the group’s 2019 impact report as evidence of the Keep American Beautiful’s value to communities: 11,911,783 hours volunteered; 218,056 acres cleaned or improved; 59,874 miles of trails and roadway picked up; 7,764 miles of shoreline cleaned and $304,952,284 of economic benefit to communities.

In addition to regular cleanups, other events, such as the “plogging” trash blast, which features a long implement that picks up litter, were also sponsored this year by Keep American Beautiful, but were delayed, canceled or held virtually.

“The scale we deliver is impressive,” Ullman said. “It seems obvious to us now, but people didn’t know about putting things in the bin.”

Micki Bozeman, executive director of Keep Brunswick County Beautiful, confirms that most of the affiliate’s varied tasks, including its litter index that assesses the volume of litter at different spots in the county, have been affected by COVID.

For whatever reason, she added, people seem to think nothing of throwing masks and gloves outside — out their vehicle window, or tossed aside after leaving a building.

“It’s everywhere, especially in the parking lots,” Bozeman said. “Which to me just blows my mind.”

Bozeman, who is also the county’s solid waste and recycling coordinator, said the Brunswick affiliate, working in the county for 18 years, focuses more on the rural areas that don’t receive the same attention as the beaches.

But the county places specially designed carts at beach areas, she said, that serve the purpose of a “big ashtray” to encourage people not to put out their cigarettes on the ground or in the sand.

Considering the unfortunate reality that people continue to litter, she said being affiliated with a well-known national organization like Keep America Beautiful encourages people to get involved in cleaning it up.

“I’ve never littered at all, and I’ve never understood at all why somebody throws something out the window,” Bozeman said. “I do think that it’s something good for communities to be part of the effort.”

Schernitzki, a 39-year-old K-12 teacher, was so appalled by the amount of litter he saw just commuting to work that he decided to clean the area himself. It turned out to be more than one person could handle.

“The thing is, if you drive around and notice litter on the side of the road,” he said in an interview, “it’s always way worse than you can see in a car.”

Even after connecting with Adopt-A-Highway and other volunteers, he said, picking up litter off the same roadways over and over again left him feeling jaded.

“There’s a road I drive on called Hibbs Road in Carteret County,” Schernitzki said. “The last time I picked that road, I filled 100 30-gallon bags in 2 miles.”

It soon became obvious, he said, that littering is a complex problem that needs a more comprehensive solution than some unpaid people cleaning up other people’s trash. Policymakers, law enforcers and lawmakers, religious and business leaders and many more representatives from the public and private sector, he said, need to be engaged.

“I see the problem as kind of a pie chart,” Schernitzki said. “I think volunteerism has a place, but it should have an equal share of the pie.”

As a science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, teacher at Roger Bell New Tech Academy in Havelock who does videography on the side, Schernitzki thought he’d start by teaching young people about the waste stream and responsible disposal.

“I think people are assuming that children are getting taught that in school, but they’re not,” he said.

Less than a year ago, Schernitzki, who transplanted to Eastern North Carolina from Seattle in 2015, founded The Litter Pirate, a tongue-in-cheek nod to his outsider status as well as his mission to crew a diverse force of young and old to conquer litter. His website includes links to humorous videos and informative podcasts to help the spoonfuls of litter education go down easy.

“The goal of The Litter Pirate is to do more than pick litter,” he said in the podcast. “It’s to fight littering, not just litter.”

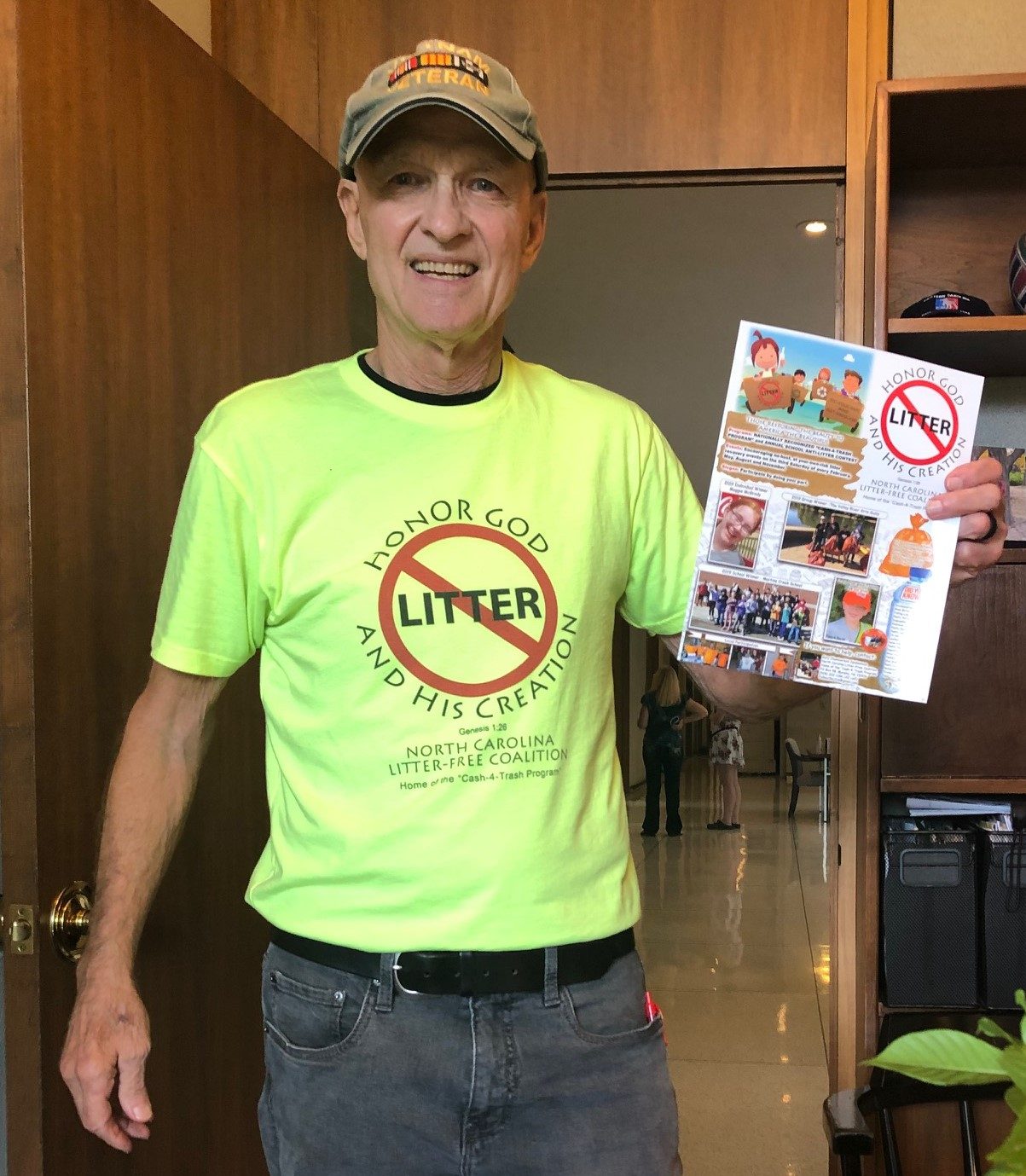

On the Western corner of the state, Gary Chamberlain founded North Carolina Litter-Free Coalition for similar reasons.

Chamberlain, 73, landed in North Carolina from Arizona about four years ago after visiting the state during one of his frequent cross-country bicycle trips.

“Every state has a litter epidemic, there is no state that is immune to this,” he said in an interview. “It’s a problem that nobody seems to be able to get their arms around.”

Roadside litter has served as a sad and alarming illustration of the social crisis with drugs and alcohol abuse, Chamberlain said. He has found liquor and beer bottles, opened and unopened, as well as needles and pill bottles.

The coalition has a “Cash-4-Trash” program, funded by local businesses and residents, that pays people $100 to fill 10 33-gallon bags with litter and answer six litter-related questions.

“It makes it a win-win situation for everybody,” he said. “Businesses love this program because they’re rewarding people who are doing something for their community. And the people who need funding have a way now to earn some funding rather than … begging for money for doing nothing.”

Chamberlain, a Vietnam War veteran and retired pharmaceutical data collection consultant, said he sees littering as a personal responsibility and doesn’t blame NCDOT for the volume of litter on roadsides.

“You, who are aunts, uncles, parents, or whatever, you put that trash there,” he said about his message. “So don’t complain to the NCDOT when they don’t have the time, money or funding to pick up the crap you left on the highway.”

That idea has received the approval of Republican politicians in the state, but Chamberlain said that the insists that the coalition remain nonpartisan. And the coalition’s slogan urging people to “Honor God and His Creation,” is about appreciating the environment, not “pushing scripture,” he said.

No matter a person’s beliefs or background, he said, “there’s something in this for everybody” because everyone hates litter.

“We’re an army of one,” he said, “consisting of many.”

Chamberlain said he hopes that the NC Litter Coalition eventually will be able to expand statewide.

Changing a careless behavior like littering, he agrees, will be a long-term effort.

“It’s a complicated thing,” he said. “I guess to get down to the basic thing is we need to educate the youth in elementary and middle school because they’re going to become the ones that actually make a difference long term.

“In my lifetime, I’m never going to see anything even close to what would make me happy, because we’re so far behind the eight ball.”