The measures put in place in March to curb the spread of COVID-19 have changed how North Carolinians consume and dispose of waste. This is the fourth installment in a series examining how advocacy organizations, local governments and state agencies are adapting to these changes.

Debris that litters the coast has been a longstanding problem for marine life, and coordinators for University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Turtle Trash Collectors program, which previously offered in-person educational activities, have changed how they reach audiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supporter Spotlight

Laura Sirak-Schaeffer, grants project coordinator and lead instructor for Turtle Trash Collectors, said in an interview that the program is an environmental education initiative funded by a grant from the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris Program.

Turtle Trash Collectors is a project through MarineQuest, the official marine science outreach program for UNCW, Watson College of Education, and the Center for Marine Science to offer young people with opportunities to explore, discover and value our marine habitats.

The goal of the program is to educate youth about the impacts of marine debris and encourage behavioral changes that will reduce its generation in the future.

“This program combines both my love for sea turtles and my passion for public education. My favorite part of my job is knowing that we are making a lasting impact by teaching everyone how they can stop marine debris,” she said.

Sirak-Schaeffer explained that marine debris has major effects on all kinds of marine organisms, especially sea turtles, which can confuse plastic bags and balloons for jellyfish. The debris can end up in their system and can get stuck, making the turtle feel full so that they stop eating. Sea turtles also can swallow fishing hooks and get caught in fishing nets.

Supporter Spotlight

“Since sea turtles are endangered species, we need to find a way to protect them from the impacts of marine debris,” Sirak-Schaeffer said, adding ways to help include reduce using plastic and use reusable water bottles, coffee cups, grocery bags and food containers instead, pick up trash to make sure it doesn’t end up in the ocean and encourage others to help.

Turtle Trash Collectors launched earlier this year new citizen-science program to better understand how COVID-19 is affecting pollution and marine debris. Volunteers are to pick an area to hold a cleanup, such as a neighborhood, park or beach, and hold three cleanups in the same area, once now, then again when quarantine restrictions are lifting, and once more when everything is reopened and back to normal. Participation information is on the website.

During each cleanup, volunteers are asked to keep track of what they collect using a data sheet and then report data so progress can be recorded.

Sue Kezios, director of Youth Programs and UNCW MarineQuest, is the principle investigator, or PI, for the NOAA grant that funds the Turtle Trash Collectors project.

Kezios said that there already was in place the Turtle Trash Collector badging program to encourage young people and their families to collect certain kinds of marine debris, single-use plastic items in particular.

“But during the early days of the pandemic I started to hear stories about how the environment seemed to be responding to the decrease in human impacts. People in the Indian province of Punjab being able to see the Himalayan mountains for the first time in many years due to a reduction in air pollution, Kezios said. “This got me thinking about litter and whether that was decreasing; and if so, what would we find during beach cleanups?”

Kezios continued that the idea to launch the citizen-science project grew out of this initial idea and the fact that they were starting to hear how kids were struggling with online learning and being quarantined at home.

“Our citizen-science project is a great way to get them outside, engaged in science and helping the environment. We asked them to do a trash survey of the immediate neighborhood surrounding their homes during the early weeks of the pandemic, then a follow up survey once their community started to open back up, and a final survey once the community is fully opened,” Kezios said. “Will the trash increase as people start to spend more time out of their homes? Unfortunately, the data so far seems to indicate this is happening.”

Sirak-Schaeffer said the idea for Turtle Trash Collectors was sparked in the summer of 2018.

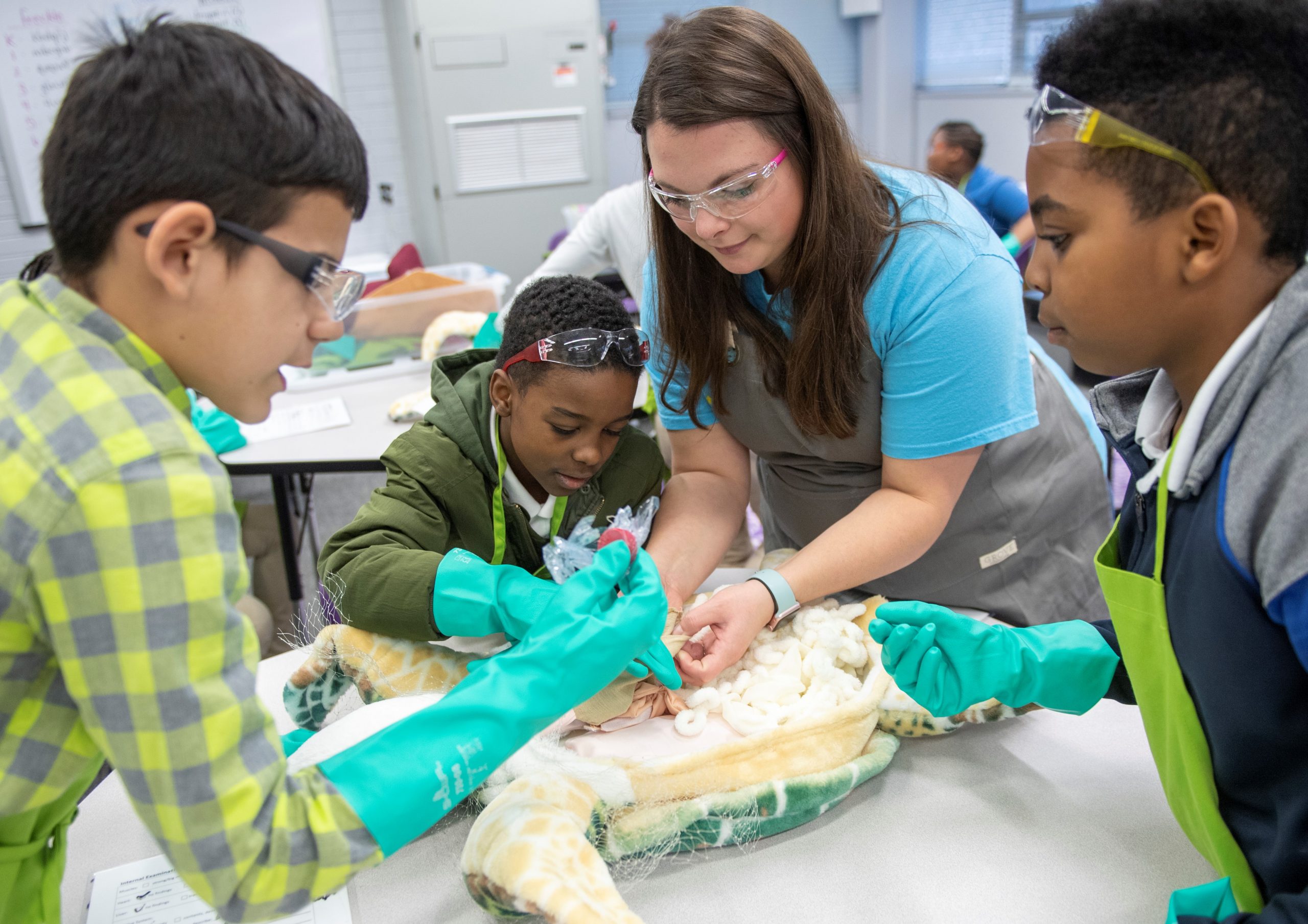

She and Kezios were “brainstorming ideas for new outreach programs and thought ‘wouldn’t it be fun to show the impacts of marine debris by simulating a sea turtle necropsy?’ We ran with the idea, applied for a grant through the NOAA Marine Debris Program, and were pleased to receive funding. We spent many hours designing and sewing our life-like sea turtle models, officially implementing programs in schools as of January of 2019,” Sirak-Schaeffer said.

They’ve traveled more than 9,000 miles and reached nearly 12,000 students and 500 teachers in southeastern North Carolina since starting the program, she said. ““We also educated 3,800 kids and 3,000 adults at public programs, mostly at the Karen Beasley Sea Turtle Rescue and Rehabilitation Center and the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher last summer.”

Kezios said she searched for a life-size and realistic-looking model and found a green sea turtle stuffed-animal toy that was easy to adapt for a necropsy simulation.

“Fortunately, our team is pretty creative, and we have a number of skilled seamstresses. I gutted the stuffed-turtles and reinforced their side walls. Another team member used cross-stitch webbing to reinforce and apply Velcro to the removable plastron,” Kezios explained. “Then we set up an assembly line and started sewing organs – muscles and heart, esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, then trachea and lungs. The most difficult part was making small resealable openings throughout the digestive tract so we could insert marine debris that a sea turtle might mistakenly ingest.”

“Fortunately, our team is pretty creative, and we have a number of skilled seamstresses. I gutted the stuffed-turtles and reinforced their side walls. Another team member used cross-stitch webbing to reinforce and apply Velcro to the removable plastron,” Kezios explained. “Then we set up an assembly line and started sewing organs – muscles and heart, esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, then trachea and lungs. The most difficult part was making small resealable openings throughout the digestive tract so we could insert marine debris that a sea turtle might mistakenly ingest.”

This is the third grant Kezios has secured that focuses specifically on the problem of marine debris.

“I think anyone who has seen coverage of a whale or sea turtle starving to death because of the marine debris they’ve swallowed or struggling to swim and breathe because they are entangled by derelict fishing gear must feel some level of responsibility for the problem,” she said. “We all generate trash, the challenge is to reduce it as much as possible and to responsibly dispose of it in an environmentally appropriate manner. Educational programs like ours can help people recognize the small ways they can contribute to a solution for a huge problem like marine debris.”

Kezios said the success of Turtle Trash Collectors was built on a previous project, Traveling Through Trash, funded by a NOAA marine debris prevention grant.

The project involved visiting schools in rural communities throughout the region with life-size inflatable North Atlantic Right Whale classroom, during which time they formed relationships with many of the school systems in coastal and southeastern North Carolina.

“The kids attended a program inside the whale and learned about marine debris origins and impacts, as well as how they can help prevent it. The program was very successful, so we were encouraged to continue our efforts with a second grant that leveraged young people’s interest in sea turtles,” Kezios said.

The idea to create stuffed turtles to simulate a necropsy, or animal autopsy, was based on the Traveling Through Trash project.

“One of the lessons we utilized with the life-sized whale was a simulated necropsy. This was so large it could only be done as a group exercise. So, we decided to focus on a different marine organism that was equally charismatic, also impacted by marine debris, and would allow for small group interactions. The sea turtle was a perfect fit,” Kezios said.

Sirak-Schaeffer explained that before the pandemic, “we would bring our model sea turtles to elementary schools in southeastern North Carolina and do a hands-on demonstration with third to fifth grade classes. Since that is not possible right now due to COVID-19, we have shifted to a fully virtual experience. We still do our simulated necropsy and help you learn about sea turtles and marine debris, but now we do it via Zoom or other online delivery platforms,” she said.

The free virtual Turtle Trash Collectors programs are hourlong sessions that features a simulated sea turtle dissection, learn how trash can get to the ocean, see how trash in the ocean can impact sea turtles and learn how to help stop marine debris, including how to become a Turtle Trash Collector. Dates are announced on Facebook for the virtual programs designed for third to fifth graders, though all ages are welcome. Younger audiences should attend with an adult if possible. The next virtual program is 11 a.m. Oct. 3. A private program for students, Scouts or network can be scheduled as well.

Since transitioning to virtual programs in March, “we have reached over 750 students, 100 adults, and an additional 300 participants. We are looking forward to a busy fall of virtual programs and would love for you to join in on the fun,” she said.

Kezios told Coastal Review Online that the team “has done a terrific job” pivoting the project to online delivery.

“They created resources that allow students to watch the virtual necropsy on the computer screen while still following along with a dissection guide and flip book. With NOAA’s permission, we’ve been able to expand our geographic delivery area and the team has provided programs to students around the country and even overseas in places like Austria and Uganda,” Kezios added.

To join the Turtle Trash Collector badge program designed for upper-elementary students in the southeastern part of the state, participants will need to sign up to receive a Turtle Trash Collector Handbook that helps identify what kinds of debris to collect for each badge, where to find it, and how to collect the debris safely. Participants will need to collect 20 debris items in each of these categories to earn badges: snack food wrappers and food packaging; drink items such as aluminum cans, plastic bottles, etc.; plastic straws; fast food containers and plastic utensils; and plastic bags.

The Turtle Trash Collectors program has helped young people who don’t live near the coast realize that land-based litter can still make its way into the ocean and harm marine organisms, Kezios said. “Marine debris is everyone’s problem and we encourage our students to choose to be part of the solution.”